Birding for Science

By Caren Cooper

April 15, 2009

Some ornithologists wake early, go into the woods and meadows, and collect data. But many researchers at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, including me, are like the Little Red Hen asking, “Who will help me gather the wheat?”

In the classic tale, no farmyard animals help the Little Red Hen. But thousands of people across the country help me gather my “wheat” by supplying bird observations. The “bread” I bake rises much higher and is much richer because, thanks to so many helpers, the data I use accumulate in numbers far greater than any one scientist could possibly collect independently.

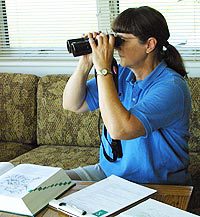

Accurate record keeping is essential for science. Birders contributing their data go beyond identifying birds to recording their sightings and additional details. Then they deposit their records online in a permanent archive—a pantry big enough for all the ingredients any Little Red Hen could use.

Birders for science follow protocols, like cooks who precisely follow a recipe, relinquishing a little freedom of individuality for consistent results.

Birders for science know to report what they do not see as well as what they do see. We call this “negative data,” be it the absence of a particular species, absence of signs of disease, or absence of a nest in a birdhouse. Normally, birders share information about the rare and exciting birds they see. But when chickadees or crows succumb to West Nile virus, or House Finches decline in an area after an outbreak of House Finch eye disease, information about rare birds won’t help us discover, track, and find reasons behind the declines in common birds. When birders submit checklists in eBird, they indicate whether every unchecked species on their checklist was not observed, rather than merely not mentioned.

Just as the animals that helped the Little Red Hen could share the feast once the bread was baked, birding for science benefits both bird research and the birders themselves. At the end of the pilot project “My Yard Counts,” one participant said, “After counting birds in my backyard, I view my backyard as habitat I share with birds, not simply as my property.” The experience of being a keener observer, note-taker, and data provider for citizen-science projects can enrich our birding experiences and add a yeasty layer of meaning to our birding fun.

Caren Cooper is a research associate in Bird Population Studies.

Originally published in the April 2009 issue of BirdScope.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library