A Phalarope Ballet on California’s Otherworldly Mono Lake

By Marie Read

From the Summer 2014 issue of Living Bird magazine.

July 15, 2014

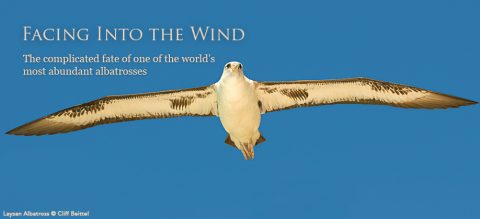

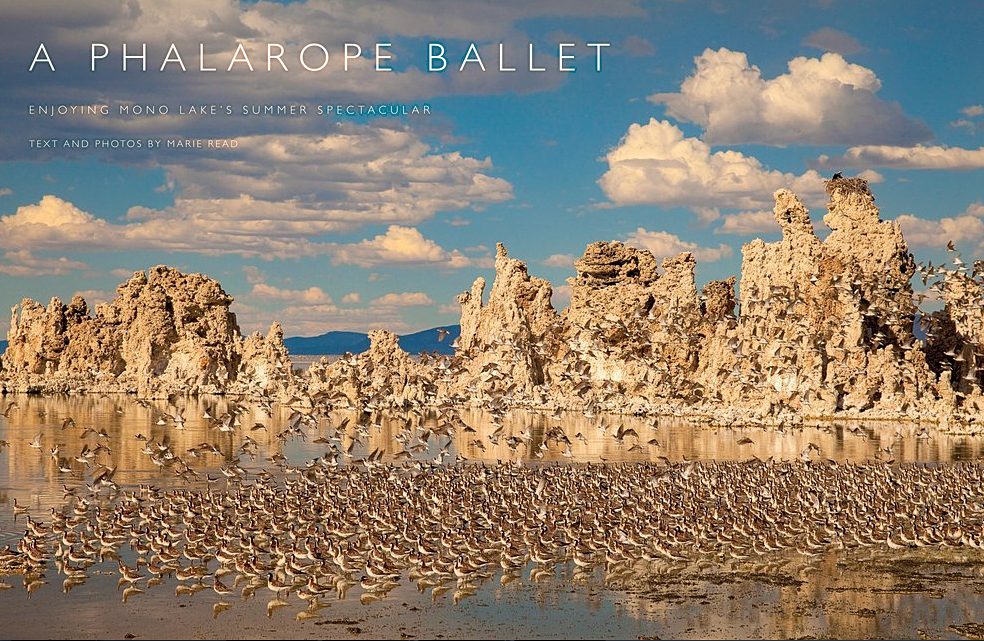

Imagine a stage awaiting a performance: a lake at sunrise, its glass-like water punctuated by tall, rocky columns against a backdrop of snow-capped mountain peaks and low volcanic craters. The show begins. A dark cloud approaches in the distance, dancing swiftly over the water’s surface. Ever-changing in shape, it twists and turns through the air, tracing elegant curves as it swirls over the bizarre tufa spires. First a compact ellipsoid shape, it morphs into a long, undulating ribbon and then splits amoeba-like into two parts that immediately merge again into one. Suddenly, at center stage, the shape-shifting dancer turns, shattering into myriad glittering fragments, each caught by the rays of the sun, and its identity is revealed: a flock of hundreds of Wilson’s Phalaropes.

The stage is California’s Mono Lake, and it’s the third week of June. Summer has barely begun—and yet for these birds, breeding season is already over and the southward pull of fall migration has begun. I’m watching the first of what eventually will be as many as 80,000 Wilson’s and 60,000 Red-necked phalaropes (about 10 percent and 2 to 3 percent, respectively, of the world populations of these two species) that will pass through Mono Lake, located in California’s Eastern Sierra region, by summer’s end. Wilson’s Phalaropes begin arriving as early as mid-June, numbers peak in late July and August, and by mid-September they are usually gone. Red-necked Phalaropes begin arriving in late July and leave by late September.

So vital is Mono Lake as a fall staging area for migrating shorebirds—not only phalaropes but also Western and Least sandpipers and others—that it has been designated a Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network site of international importance. Factor in the shorebirds found here in the summer— nesting American Avocets, Spotted Sandpipers, and threatened Snowy Plovers (11 percent of the California population nests at Mono Lake). Don’t forget the 65,000 nesting California Gulls and the million or so migrant Eared Grebes that stage here in fall after the shorebirds have left. Why are so many birds drawn here? For human visitors, Mono Lake’s spectacular, otherworldly scenery of tufa towers (formed by limestone deposits) and volcanic outcrops is a visual feast. For birds the feast is real: they’re here for the food. Mono Lake has alkaline, highly saline water that supports no fish, yet it teems with other aquatic life. Algae, at the bottom of the food web, support trillions of tiny brine shrimp plus the aquatic larvae and pupae of vast numbers of alkali flies, whose swarms blanket the shore in summer. This simple but highly productive system allows countless breeding birds to raise young and migrants to refuel.

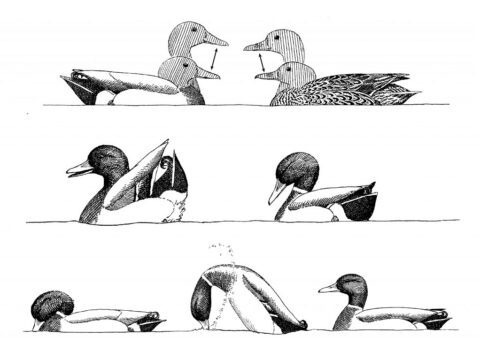

To feed on the lake’s bounty, phalaropes go for a spin, literally. They pirouette gracefully on the water, constantly paddling with their specially adapted feet. The toes of Wilson’s Phalaropes I are edged by narrow fringes, and those of Red-neckeds by larger, more coot-like lobes. The vortex created by spinning stirs prey up within reach. The bird touches its slender bill to the water’s surface and the prey item is instantly drawn up by surface tension and swallowed. It’s fascinating to watch even a single phalarope feeding, but it can be hard to drag oneself away from the mesmerizing sight of hundreds, or even thousands, all twirling at once.

The earliest Wilson’s Phalaropes to arrive at Mono Lake are adult females, most of them still in breeding plumage. Meanwhile, the species’ breeding grounds in the marshes and prairie wetlands of western North America are filled with abandoned single fathers. The sex roles typical in most of the avian world are reversed in all three phalarope species—Wilson’s, Red, and Red-necked. Females are the bigger, bolder, and more brightly colored of the two sexes, and it is they that compete with each other over mates, whereas the males have sole responsibility for raising the young.

Soon after laying a clutch of eggs, most female phalaropes immediately desert their mates, leaving them to incubate the eggs and care for their precocial chicks alone. Females may repeat the process with an additional male or males during the same season (known as serial or sequential polyandry) or start the first leg of their migration. As soon as the males’ parental duties are complete, they follow the females southward, followed later by the juveniles, to join the ever-growing numbers at Mono Lake.

Seeing thousands of phalaropes take flight and swirl as one across the water’s surface in a tightly coordinated aerial ballet is unforgettable. More often than not, it’s hard to say what sends them all up, but sometimes the cause is quite clear. Late one afternoon I was watching a flock that had gathered around me while I sat near the water’s edge, when suddenly a dark shape rocketed past me with a piercing scream of wings, sending the panicked phalaropes scuttling over the water in a huddled mass. A Peregrine Falcon had strafed the flock.

Flocking provides some measure of security from predation: the more phalaropes there are, the smaller chance any individual has of being targeted. But they are no match for a hunting Peregrine Falcon. Over the next few days, I watched two of these powerful raptors regularly stooping on the phalarope flocks, picking off stragglers, an experience that left me feeling both thrilled and deeply shaken by the raw force of nature.

After several weeks of gorging on the lake’s bounty, the Wilson’s Phalaropes have undergone a complete molt and accumulated fat, sometimes doubling their weight. Clad in new feather coats and fueled for their journey, they fly essentially nonstop to their wintering grounds in the highlands of Bolivia, Peru, and all over northern Argentina.

Reflecting on the birds’ whereabouts on the autumn equinox in 1987, the late David Gaines (co-founder of the Mono Lake Committee, the organization charged with protecting the lake) wrote, “the phalaropes—minus the few that foddered falcons— are 3,000 miles away in South America, where they are cavorting with flamingoes on saline lakes high in the Andes.” In my mind’s eye I can see them performing their phalarope ballet in that Southern Hemisphere environment that mirrors the alkaline mudflats and strange waters of Mono Lake, until the approaching spring makes the pirouetting dancers restless, drawing them northward to breed once more.

Marie Read’s new book Sierra Wings: Birds of the Mono Lake Basin is now available.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library