Lecture and New Book Chronicle Epic Quest for Birds-of-Paradise

Text by Pat Leonard; photos by Tim Laman October 19, 2012

Thirty-nine of the most gorgeous, outlandish animals in the world—the birds-of-paradise—live only in New Guinea, associated islands, and adjacent tropical Australia. Though they’ve been known for centuries from paintings and specimens, it’s only now that all 39 can be admired in glorious photographic detail, thanks to ground-breaking work by Cornell Lab biologist Ed Scholes and National Geographic photojournalist Tim Laman.

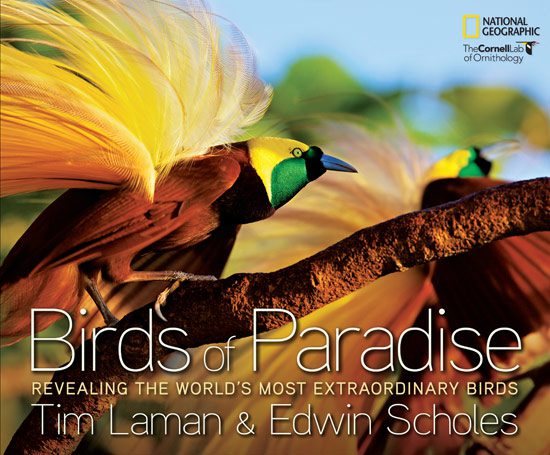

On October 13, Scholes and Laman gave a lecture on their work to a packed house at Cornell University. Their talk kicks off a lecture tour, TV documentary, and museum exhibit jointly developed by the Cornell Lab and National Geographic. The pair astonished the audience with stunning photos, video, and sounds of the birds, their plumage and behavior so far out of the ordinary they almost defy the imagination. The pictures are now part of a gorgeous coffee-table book (on sale Oct. 23 and available for preorder now), copublished by the two organizations. Cornell Lab writer Pat Leonard was at the lecture, and she captured the excitement in this review:

The walls of the auditorium reverberated with the hum of conversation and a sense of anticipation, punctuated by eerie recorded bird calls—just a hint of the eye-popping oddities to come. Cornell Lab biologist Ed Scholes (left, with laptop) and National Geographic photojournalist Tim Laman (right, with camera) took the stage to guide the audience through New Guinea’s remote swamps and cloud forests. Following in the footsteps of legendary explorers like Ferdinand Magellan and Alfred Russel Wallace, Tim and Ed spent 544 days in the field over 8 years, visiting 51 sites to document all 39 known species of the birds-of-paradise. Along the way, Tim Laman shot more than 39,000 photographs. “We can’t show them all,” he quipped. By the time the evening was over, you rather wished he would have.

Tim and Ed were entertaining speakers with a tag-team style to their commentary. They described journeys to 11,000-foot mountaintops, home to the Splendid Astrapia, and to lowland swamps where the Twelve-wired Bird-of-paradise woos a female by brushing her face and throat with his long wirelike tail feathers. (Click on species’ names to see videos of them.)

Most of the remaining bird-of-paradise species inhabit the middle ground, laying claim to small slivers of territory and to unique courtship behaviors. “The males play no role in the care of the young,” Ed explained. “Their only goal is to mate with as many females as possible. So it’s the females who call the evolutionary shots.”

The more subtly beautiful females obviously have a taste for the outlandish. Over the millennia, they have chosen males with ever more iridescent colors, flashy plumes and wires, or fancy footwork. It’s “survival of the sexiest,” according to Ed. In evolutionary biology lingo, that’s “sexual selection.”

Some species put their efforts into brilliant and varied colors to get attention. The male Wilson’s Bird-of-paradise has evolved bright blue skin on its head, yellow, green, and red feathers, purple legs and feet, and two longer tail plumes that form tight outward curls. He spends his days fussily tidying his display court.

The King of Saxony Bird-of-paradise banks on embellishment and behavior. Laughter accompanied a video clip showing him bouncing enthusiastically on a branch, making a loud crackling call, and waving long plumes that sprout from skin behind his eyes. The human equivalent, Tim pointed out, would be 10-foot appendages jutting from our temples.

Occasionally, it seems the courtship adaptations might be a bit of a nuisance. The Ribbon-tailed Astrapia’s tail is three times the length of its body. Tim and Ed said they’ve seen this bird checking for the whereabouts of its tail before taking off because its plumes sometimes get wound around trunks and branches during foraging.

The sicklebills use shapes and poses to attract attention. These “transformers” of the avian world include the Black Sicklebill who performs many wing shrugs before spreading his feathers up and over his head to create a startlingly unexpected hooded cloak (3:06 into video clip). Tim and Ed showed the first video ever taken that captures this behavior with both sexes participating—the female going beak-to-beak with the displaying male to play her part in the mating dance.

Another favorite was the Superb Bird-of-paradise, also known as the Greater lophorina. Deftly balancing on a log, he raises special feathers that transform him into a black blob punctuated with iridescent blue markings that look rather like a wide grin and two blazing eyes. He makes a loud snapping noise to accompany his bounding dance steps around the female (at 0:55 in the video clip).

Tim and Ed made one of their most intriguing discoveries when they decided to capture the “ballerina dance” of the Wahnes’s Parotia from the female’s point of view. It took multiple cameras and two weeks of trying. Tim whiled away long hours in the blind reading The Count of Monte Cristo on an e-reader and counting the number of finger-swipes it took to finish (11,000). Looking down from a branch above the courtship display area reveals a much different view than from ground level. We see a bobbing, weaving, black ovoid shape with flashes of iridescent yellow breast feathers and a wiggling blue line that marks the back of the male’s head, highlighting his movements.

The presentation closed with a high-canopy image of the Greater Bird-of-paradise, bathed in golden morning light, taken with the ingenious “leaf-cam.” (You’ll be able to read more about it in the October issue of Living Bird, our member magazine) The bird flourishes its russet wings and its yellow and cream-colored plumes. The impenetrable rainforest spreads to the horizon. The image prompted an audible gasp from the audience and a sustained standing ovation.

Tim and Ed hope the exotic evolutionary adaptations of the birds-of-paradise will exert another kind of attraction: drawing public attention to all that could be lost if threatened rainforest habitat is not protected around the world. You can donate to support our work here.

(This article was written by Pat Leonard. Photographs by Tim Laman. The Birds-of-Paradise book and exhibition are collaborations by the Cornell Lab and National Geographic.)

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library