Winter Ice Can Force Red-necked Grebes to Make Other Plans

By Gustave Axelson and Marshall Iliff

April 13, 2015

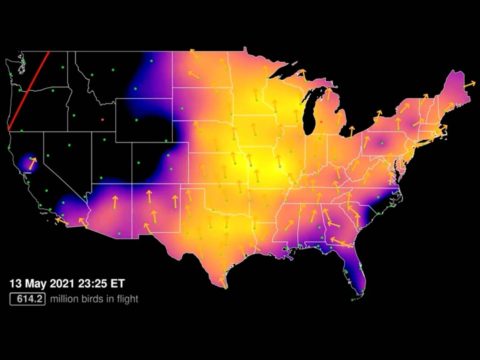

For the past six weeks, the Cornell Lab’s eBird team has been buzzing about the potential this spring for inland fallouts of Red-necked Grebes around the Appalachians region. That happened during the frigid winter of 2014. And in early 2015, as thermometers seemed stuck in the single digits, it looked like all was set for a repeat.

Fallouts are the stuff of birding legend—a phenomenon where bad weather forces masses of migrating warblers, orioles, and tanagers to land for cover all at once. They’re typically seen along the Gulf Coast. In spring 2014, fallouts of a different kind occurred throughout the Northeast, when eBirders reported Red-necked Grebes scattered on inland small ponds and rivers—far away from their usual big-water haunts on the Great Lakes and Eastern Seaboard at that time of year.

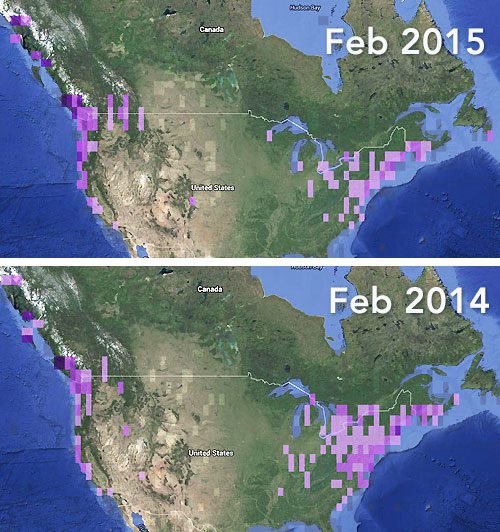

Looking back at what caused this inland grebe fallout, the eBird team noticed that the 2014 Great Backyard Bird Count, in February, had tallied unusually high counts of Red-necked Grebes on inland bodies of water, from New England to North Carolina and Ohio to Tennessee. In a normal winter, the majority of Red-necked Grebes overwinter along the Atlantic Coast in the Northeast, with some smaller populations overwintering on Lake Ontario. What were so many doing inland?

The winter of 2013-14 was historically cold, and Great Lakes ice cover exceeded 92 percent (50 percent ice cover is about average). With America’s easternmost Great Lake just about frozen over, the grebes were forced off of Lake Ontario and headed south and east to find open water—hence the high inland grebe counts in the GBBC. And then in March 2014, as grebes migrating from the Atlantic Coast looked for their traditional rest stop on Lake Ontario, they instead found ice and probably had to reverse course, further bolstering the numbers of inland grebes. Since these grebes were probably short on fuel, fallouts ensued as these grebes landed on whatever open water they could find south and east of Lake Ontario.

Looking back further into the eBird data, this March pattern also happened in 1993 and again in 2003. And it looked like the same recipe for grebe fallouts was cooking up this year, with another epically cold winter and the Great Lakes again more than 90 percent frozen.

But as team eBird closely monitored the Red-necked Grebe reports in the East this winter and spring, the large inland congregations of grebes never materialized. What happened? There are a few possible explanations.

It could be that when Lake Ontario froze on consecutive years back-to-back, some grebes changed their behavior, as they learned not to attempt to winter on Lake Ontario. It is also possible that many of last year’s grebes that were forced off Lake Ontario died, either as a direct result of the freezing in February or because they were simply less healthy for their spring migration after the freezeout.

The two options above would explain the lack of a midwinter movement, but what about March? This year, despite high ice cover on the Great Lakes, large patches of Lake Ontario had opened up again in March. So grebes migrating from the Atlantic found open water at the right time take a rest on Lake Ontario on their journey back northwest toward breeding areas in Canada and Alaska.

As of now, it seems grebes are finding no interruptions to their regularly scheduled migration on the northwest shore of Lake Ontario. The lake is ice-free in the Toronto area, and on April 5 one dedicated Canadian birder carefully counted 1,529 Red-necked Grebes there on a single eBird checklist!

For more information:

- More sightings and patterns from the 2015 Great Backyard Bird Count

- Red-necked Grebe eBird distribution map

Gustave Axelson is a Cornell Lab science editor; Marshall Iliff is a co-leader of eBird.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library