Not Just Sparrows and Pigeons: Cities Harbor 20 Percent of World’s Bird Species

By Andrea Alfano April 29, 2014

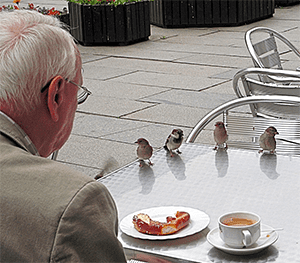

Rock Pigeons, House Sparrows, and European Starlings are widely known as “city birds,” and with good reason. These three species (plus Barn Swallow) occur in more than 80 percent of cities according to the first-ever global study of biodiversity in urban areas, published earlier this year in Proceedings of the Royal Society B. But there’s more to cities than this narrow cast of avian urbanites: cities also retain more of their region’s native diversity than previously thought, according to the study’s analyses of bird and plant census data. So take heart, your next city stroll has much more to offer than just a few ubiquitous species.

In fact, at least 2,041 species—20 percent of all known bird species—live in the world’s cities, according to the research. Unlike previous studies, which have focused on single cities or regions, this study spanned six continents, compiling data on birds from 54 cities and plants from 110 cities. The researchers themselves hailed from North America, Europe, Australia, and South Africa.

“One of the big paradigms of urban ecology is that the biota of the world’s cities is homogenized,” said lead author Myla Aronson, a researcher at Rutgers University and a Cornell University alum. “But we showed that at the global scale, cities are primarily retaining the unique composition of their geographic location.”

This means that although there are a few species that can truly be considered ubiquitous “city birds,” they are in the minority—a finding that wouldn’t have been possible without the global scope of this study. In fact, the list of species that you can find across 80 percent of the world’s cities amounts to just the four species mentioned above. The full list of birds found in cities includes nearly three-quarters of all bird families. Cities even provide habitat for rare species, including a total of 36 bird species identified by the IUCN Red List as threatened with extinction, the study said.

For many people, this remarkable diversity is often overshadowed by the notion that humans have almost entirely forced nature out of cities. A recent study by a different group showed that many urbanites fail to notice increases in biodiversity even when they happen.

“If you’re not particularly connected with nature, it’s easy to just not see what’s there,” said Karen Purcell, project leader for a Cornell Lab project called Celebrate Urban Birds. Purcell aims to change this “biodiversity blindness” by encouraging people to learn about and look for just 16 bird species that are commonly found in cities. It’s intended as a manageable introduction to the amazing diversity that can be found in cities.

For many city-dwellers, knowledge of just these few species leads them to become more aware of urban biodiversity in general, and encourages them to take pride in their city’s non-human life in addition to its human culture.

“We want to get that bug into people to watch,” said Purcell.

Urbanites are right to realize that cities are by no means ideal habitats for birds. Many species still manage to survive in them, but only around 8 percent as many species are found in cities as in the non-urban areas surrounding them. That’s why part of the goal of Celebrate Urban Birds is to inspire people living in cities to take action to support their urban biodiversity.

“Providing native vegetation is something that not only city planners can do, but that people can also do on a smaller scale,” said Frank La Sorte, a researcher at the Cornell Lab and an author of the urbanization study.

Cities with the least amount of urban land cover have the highest densities of bird species, according to the study. Parks and community gardens filled with native plants play an important role in maintaining bird species, but providing even small patches of vegetation, like hanging basket plants or container gardens, can help to attract birds to urban areas.

As of now, cities cover only 3 percent of the Earth’s terrestrial surface, but this doesn’t mean that the effects of urban greening efforts are insignificant. It’s not only the size of a city that affects biodiversity—location is important too.

“People tend to settle in regions that are already very species-rich because these are often the best areas in terms of climate and agricultural activities,” said La Sorte.

Cities may only take up 3 percent of the Earth’s land cover, but they are currently home to more than half of the world’s human population. This makes increasing awareness of biodiversity in cities even more crucial, because people can’t care about or protect things that they don’t notice. But actions as simple as participating in a citizen science project like Celebrate Urban Birds can open one’s eyes to biodiversity for a lifetime

“Once you see, you don’t ever stop seeing,” said Purcell.

For more on biodiversity in urban areas:

- see the study in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, and its companion study on plants in urban areas

- try out the Celebrate Urban Birds citizen-science project

- get some advice on Urban Gardening for Birds from Celebrate Urban Birds

- read our movie review of Birders: The Central Park Effect

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library