Project SNOWstorm Seizes the Moment to Take a Closer Look at Snowy Owls

By Pat Leonard May 24, 2016

The massive Snowy Owl irruption of 2013–2014 (the biggest in decades) captivated birders and nonbirders alike with unexpected glimpses of an avian superstar with hypnotic golden eyes. But that winter’s phenomenon was also an opportunity for science to learn about the lifestyle and biology of an arctic species we really know very little about.

UPDATE May 24, 2016: The GPS transmitters that Project SNOWstorm deployed in 2014 gathered precise locations for dozens of owls. A National Public Radio team used those coordinates to follow one of the owls, a male named Baltimore, from his 2014 winter location in Maryland to his 2015 winter location on Amherst Island, Canada. They put together a wonderful short documentary—both charming and amazing in its level of detail about the owl’s journey (at right).

The remainder of this post is the original article from January 2014. Read on for details about how the scientists of Project SNOWstorm laid the groundwork for this farsighted project.

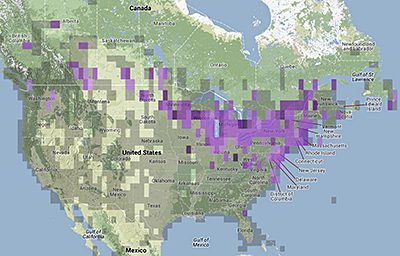

The first hint of the massive influx came from birders tracking the growing irruption through eBird, a story that was eventually picked up in the New York Times and elsewhere. Soon after, the irruption was so clearly exceptional that naturalist and Pulitzer-nominated author Scott Weidensaul and colleagues saw it as a chance to learn even more using the newest methods in tracking, and DNA and feather analysis. Weidensaul and approximately two dozen researchers and supporters have come together almost serendipitously to form Project SNOWstorm. The scientists are attaching GPS transmitters to some of the birds, giving all of us the equivalent of a high-tech “ride-along” with our arctic visitors.

“People are stepping up in a way I’ve never seen before,“ says Weidensaul, “We’re getting help from labs that do DNA blood work, from licensed banders, experts with GPS transmitters, state and federal wildlife vets and pathologists, rehabbers, and website developers, not to mention the vital observation information we get from citizen scientists using eBird.”

The main swath of eBird Snowy Owl sightings stretches from Wisconsin east to New England, through the Northeast, and down the Atlantic Coast. At least one bird has reportedly turned up in Florida—a long haul from its usual arctic stamping grounds.

When a likely candidate is located, licensed banders capture the bird to collect a blood sample, take measurements, note the condition of the bird, and take a tiny snippet of feather for analysis, in addition to banding it. DNA and feather tests can reveal a lot about the condition of the bird and even what toxins it was exposed to here and in the arctic. Then they give the owl its own little backpack.

“These are special solar-powered GPS transmitters made by Cellular Tracking Technologies,” Weidensaul explains. “They record the bird’s location and are programmed to send a data point every 30 minutes via cell phone towers. The packs weigh less than 40 grams [1.4 oz], which is fine for a bird as big as the Snowy Owl. It doesn’t interfere in any way with flight and we’re making sure to tag only healthy birds.” (Snowy Owls typically weigh 4–5 pounds and can top out at more than 6 pounds.)

The goal is to tag 20 to 25 owls with these transmitters. As of this writing two owls have been tagged with several more expected to be outfitted this week. Those first two have been up and running since the end of December. SNOWstorm is tracking an owl in Wisconsin dubbed “Buena Vista” and another called “Assateague” for the island of the same name off the coast of Maryland—although that bird has since traveled up the New Jersey coast. Animations of their tracking data make it clear the two birds have much different hunting strategies.

This video from Project SNOWstorm shows the level of detail that Buena Vista’s transmitter has been able to send to the researchers about where the owl spent its time:

“The Wisconsin bird is hanging around within a one-mile radius of where it was tagged, in prairie and marsh,” says Weidensaul. “The data are so precise that we can see the even spacing of dots where the owl has been perching and recognize them as specific telephone poles when we zoom in on Google Earth.”

Assateague is a rolling stone. He’s been zigzagging all over the place, resting by day and traveling or hunting by night. He’s apparently been snagging sleeping waterfowl offshore that are literally sitting ducks for this large raptor.

“We never, ever put up real-time data showing the birds’ locations,” Weidensaul says. “As much as we know people want to see these owls, we don’t want to be responsible for a deluge of onlookers that could disturb the birds or unintentionally cause harm.”

The technology has some limitations. Because the transmitter is powered by sunlight, the lack of it means no data is phoned in. The Wisconsin bird “went dark” after a long stretch of cloudy weather and the project is hoping for a sunny spell to get the pack powered up again. Now both Assateague and Buena Vista have moved into “dead zones” lacking sufficient cell coverage. But no data will be lost. Weidensaul says the units can acquire and store up to 100,000 GPS locations without cellular coverage. If and when the owl comes back into cellular range, each transmitter will phone in with all its accumulated data. However, cost is a limiting factor. Each transmitter pack costs about $3,000.

So what happens to all the information gathered by SNOWstorm? Weidensaul admits the project is still a “work in progress” but he’d like to see the website become a central portal for the scientific findings tied to this irruption. This winter’s Snowy Owls are already debunking some commonly held notions about why they came here.

“Everyone assumes that Snowy Owls come south because of a shortage of food in the Arctic,” Weidensaul said, “But the opposite is true. This summer there were plenty of lemmings, the birds gorged themselves, and had such a successful breeding season that we’re seeing the results of that bumper crop. We know from banding work by people like Norman Smith in Massachusetts, who has been studying Snowy Owls for the past 30 years at Logan Airport, that most of them are healthy, and that the majority of them do make it back to the Arctic.”

We may never see another Snowy Owl irruption this big again, but some owls always appear in southern Canada provinces and northern U.S. states. And if an owl with a functioning backpack comes back south in coming years, its transmitter will have some unbelievably good GPS data to send in.

“Think of what we could learn about where they’ve been, where they stopped, how long it took them to get there, and so on,” Weidensaul says. “This is big, this is a once-in-a-lifetime moment.”

How you can help

- Submit Snowy Owl sightings to eBird

- Find out more about Project SNOWstorm

- Send in your Snowy Owl photos that show spread wings or tails—this will help scientists determine the age and gender of the birds

- Donate to the project’s IndieGoGo fundraiser to help them put transmitters on more owls

For more about Snowy Owls, check out:

- Banding Snowy Owl Chicks With Researcher Denver Holt

- A Live Visit to the Snowy Owl Nest on Our Live Cam

- A Season of Snowy Owls, in the Spring 2014 Living Bird magazine.

- A Snowy Owl Sequel?, January 2015 blog post

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library