Mockingbirds Can Learn Hundreds of Songs, But There’s a Limit

By Mary-Russell Roberson

From the Spring 2016 issue of Living Bird magazine.

April 12, 2016

The Northern Mockingbirds that live on the campus of North Carolina’s Elon University might not know it, but they are a well-studied bunch. While the birds go about their business—singing, pairing up, fighting, and raising young—biology professor Dave Gammon and his students go about theirs, recording and analyzing the songs of these vocal virtuosos.

Mockingbirds sing a lot. Both females and males sing, and they can be heard any month of the year and any time of the day—and even at night.

Their singing is not only voluminous but also diverse. Mockingbirds string together series of repeated phrases, some of which are imitations of other bird species. A male may have several hundred phrases in his repertoire, although some will be in much heavier rotation than others. A typical song is about equally divided between mimicked phrases and mockingbird-specific vocalizations.

Although most bird species only learn songs during a critical period in their youth, mockingbirds have long been considered open-ended learners—meaning that they learn new songs throughout their adulthood. Parrots and European Starlings are examples of open-ended learners. However, Gammon’s research has cast doubt on this long-held assumption about mockingbirds, surprising even himself.

Gammon began studying mockingbirds in 2006 after joining the biology department at Elon University in central North Carolina. As a biologist, he was drawn to bird song because he had a good ear (he minored in music in college) and liked being outdoors. He’s always enjoyed imitating other people’s voices and mannerisms. “Studying mimicry was a natural fit,” he said.

One of the first questions he tackled was why mockingbirds mimic some species but not others. Gammon analyzed his recordings of campus mockingbirds and found that they most often mimicked the Carolina Wren, Tufted Titmouse, Blue Jay, Northern Cardinal, and Eastern Bluebird. Never-mimicked species included the Mourning Dove and Chipping Sparrow.

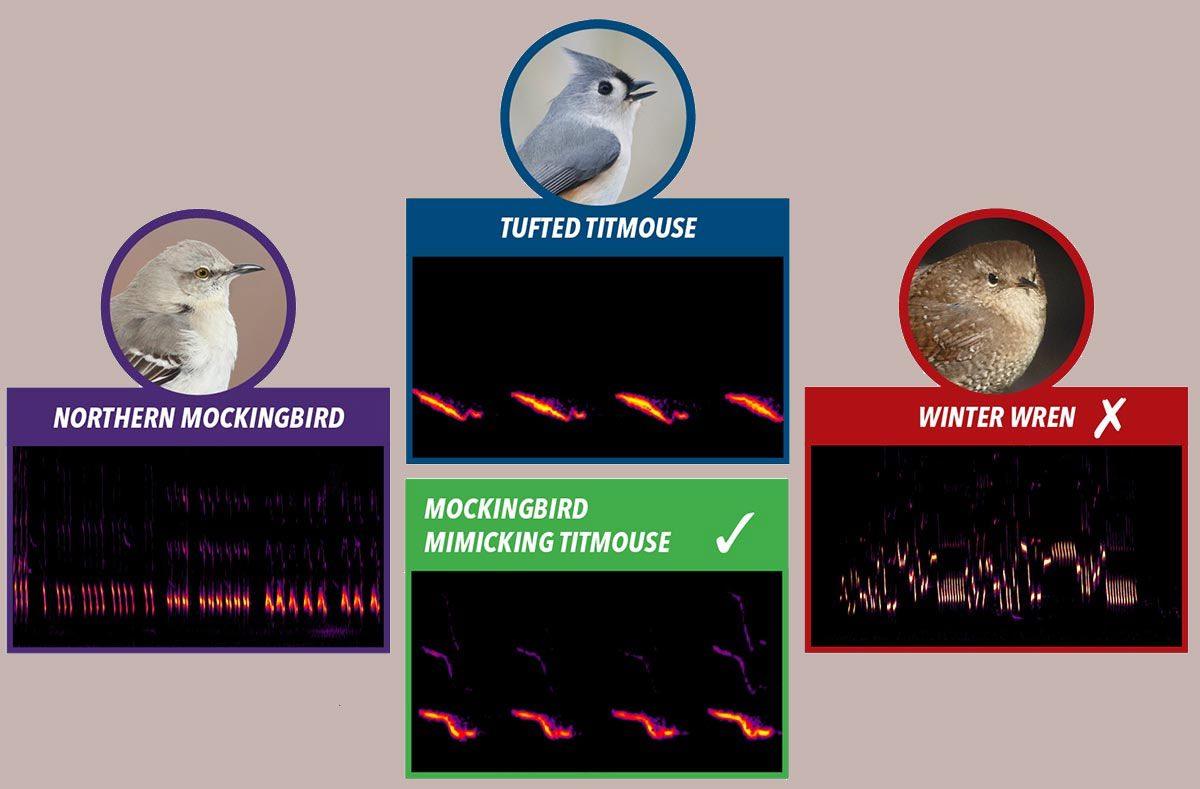

He tested several hypotheses and found that mockingbirds mimic birds whose songs are similar in pitch and rhythm to their own vocalizations. “When a Tufted Titmouse sings, it already sounds similar to something a mockingbird would sing,” Gammon said. The Mourning Dove is too low and slow, and the Chipping Sparrow is too high and fast.

As a follow-up, he designed an innovative experiment: for six months, he broadcast eight novel songs from four outdoor speakers on campus for two hours a day. Half were recordings of birds that don’t live in North Carolina and half were computer generated. More importantly, two of the exotic bird songs and two of the computer-generated songs were similar in pitch and rhythm to mockingbird-specific vocalizations. Gammon expected that the campus mockingbirds would imitate the real and computer-generated songs similar to theirs, but not the ones that were dissimilar.

In fact, they didn’t imitate any of the songs. Gammon combed through hours of recordings from 15 adult banded mockingbirds from that year and several years afterward and found not a single imitation of any of the new songs. “I simulated a six-month invasion of eight new species and none of their songs were picked up by the mockingbirds,” Gammon said. “I was quite convinced they would pick up something, and the fact that they didn’t was shocking.” (However, on two occasions he did hear a Brown Thrasher of unknown age mimicking one of the new songs.)

Looking at his results, Gammon began to wonder whether mockingbirds are truly open-ended learners.

He delved deeper into the question by analyzing recordings he collected of 15 banded adult males over several years. He compared the recordings of older birds to those of their younger selves to see whether older birds sang a greater variety of mimicked phrases. If so, it would provide a clue that they learn new songs throughout adulthood. His results showed no difference on average in the birds’ mimetic repertoire as they aged.

“I’ve found no solid evidence that mockingbirds are truly open-ended,” he said. “Perhaps open-ended song learning is rarer than we thought.”

Eliot Brenowitz, a professor in the Department of Biology and Psychology at the University of Washington, who was not involved in the study, called Gammon’s loudspeaker study interesting, but said he would be cautious in drawing conclusions. “A negative result is challenging to interpret,” he said. “Playing songs over speakers may not pass some motivational threshold for a bird to copy.”

What does motivate mockingbirds? Gammon would love to know. He’d also like to know why mockingbirds mimic in the first place. Do females prefer males that have a larger repertoire of mimicked phrases—and if so, why? And how do young mockingbirds learn mimicked phrases—from adult mockingbirds or directly from the mimicked species?

Gammon knows that the answers to these questions won’t come easily. “I envy those social scientists,” he said. “They can say to their subjects, ‘Write your name here and answer my questions. Oh, and write your answers in English.’”

In the absence of such a questionnaire, Gammon will continue to interview mockingbirds the only way he can: by waking up early, swatting at mosquitoes, and recording them as they sing…and sing…and sing.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library