On the Antarctic Peninsula, Scientists Witness a Penguin Revolution

Story by Hugh Powell; Photographs by Chris Linder

From the Winter 2016 issue of Living Bird magazine.

January 26, 2016Penguins don’t tend to travel alone. Yet here was one all by itself on the cobblestone flats of Litchfield Island. It was an Adelie, standing knee high and looking like the quintessential penguin: ink black and linen white, with a wide eye and an air of having momentarily forgotten what it was up to. It plucked a pebble from the ground, flung its flippers wide, and toddled away.

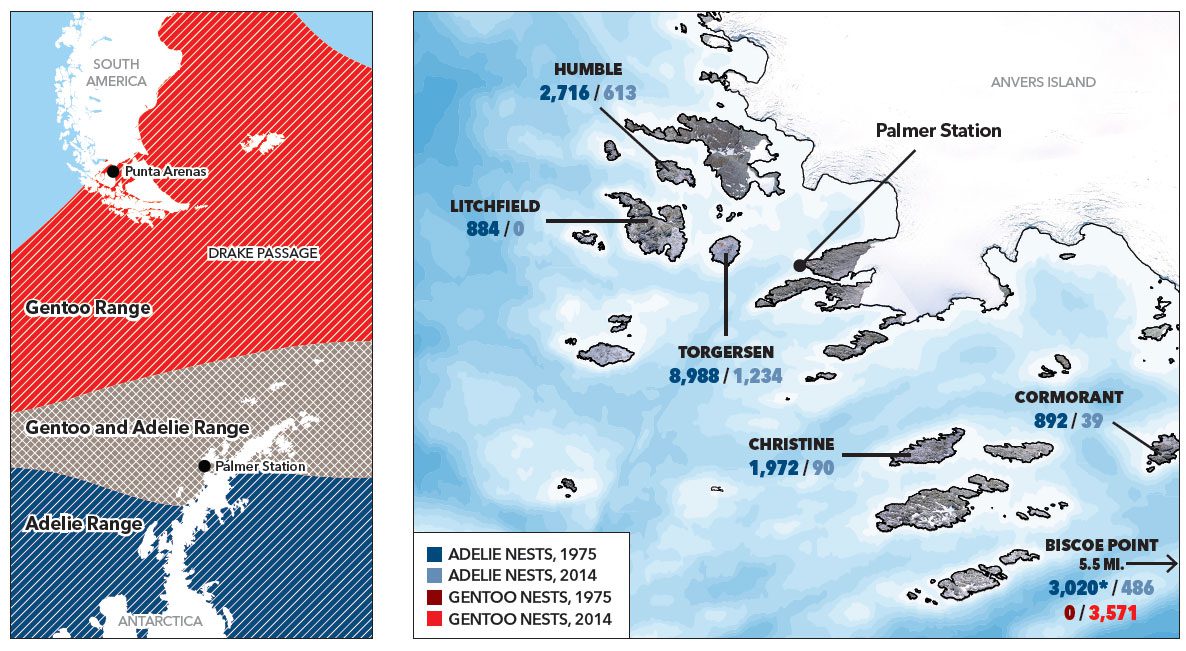

This was clearly a young bird. An Adelie needs between five and eight years to learn how to arrange a few hundred pebbles into a passable nest, attract a mate, and get a couple of eggs laid early enough to survive. This bird had only the barest idea of why it had picked up the rock or where it was taking it. One thing was certain: it wasn’t going to build a nest on Litchfield Island. Although this beach once held more than 800 Adelie nests, since 2007 it has been empty and quiet.

A couple of decades earlier, another penguin had clambered up onto a similar beach called Biscoe Point, eight miles away. It was a Gentoo Penguin, a slightly larger and more fashion-forward species, with a white blaze across its eyes and a bill that seemed, in the monochrome of Antarctica, almost unnecessarily red. It soon set to work gathering its own stock of pebbles, and by the time Donna Fraser came by and found it, in the austral summer of 1993, there was a small group of 14 nests underway. They were the first Gentoo Penguin nests ever recorded in the vicinity of Palmer Station.

Fraser took me to that exact spot at Biscoe Point in January 2015. Riding in two Zodiac inflatable boats our team nosed through an ice-choked inlet and tied up to a steel mooring pin embedded in a 10-foot rock face. As I climbed up and looked over the edge, I came face to face with about 30 adult gentoos. Each had a duo of chicks at its feet, their heads snuggled under a parent’s belly, their fuzzy gray behinds collecting snowflakes.

In the distance, gentoos covered every available surface: along the shoreline; on the rocky benches that rose into the mist; behind us to the edge of the blue glacier; and around the horseshoe-shaped inlet to the next point. It was 21 years after the very first gentoo had arrived, and I was looking at about 3,600 nests.

“It was this gigantic ecological aha,” Fraser said of the year-by-year increase. “It was like: We have a few. We have a lot. We have a ton. They’re taking over the world now.” At the same time, Adelie Penguin numbers in the region fell by more than 80 percent.

Donna’s husband, Bill Fraser, has studied penguins at the U.S. research outpost of Palmer Station since the 1970s. Donna joined him in 1991, and the pair—who run the Polar Oceans Research Group from their home in Sheridan, Montana—have studied Palmer’s seabirds ever since. What began as basic research in Antarctic ecology soon turned into front-row seats to a penguin revolution.

This region—the Antarctic Peninsula—is the fastest-warming place on the planet. Average winter temperatures are up 12°F over the last 65 years (that’s five times the average global rise). No clearer example exists in the world of the pace at which climate change is coming around the curve at us.

“It’s not so much that it matters if one penguin replaces another,” Donna said. “I’m not going to weep over the death of 10 Adelies or 100 Adelies, or in this case thousands of Adelies. But why are they going?” If we don’t ask that, she said, “We’re missing the bigger picture.”

To the End of the World

Palmer Station—where I spent five weeks in early 2015 writing about National Science Foundation research—lies near the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, 700 miles due south of Tierra del Fuego. Getting there requires making your way to Punta Arenas, Chile; rubbing a toe on the Ferdinand Magellan statue for luck; and then crossing the Drake Passage on an icebreaker.

The southward voyage takes a week—a day to get clear of Argentina, three days without sight of land, a day to get used to icebergs, and then a couple of days to adjust to the scale of Antarctica as the South Shetland Islands slip astern. These are days filled with humpback whales rolling at the surface; jagged peaks towering overhead, permanently capped with a schmear of snowpack 50 feet thick; and the orange-pink rays of the sun lighting clouds at 1:00 a.m.

When Palmer Station comes into view, it’s an outpost of four main buildings, a couple of fuel tanks, and some large, complicated radio antennas. It sits on a bare toe of rock on the south side of 40-mile-long Anvers Island, which is studded with 9,000-foot peaks and draped in an ancient cloak of glaciers. The latitude—64° South—means summer is chilly and wet rather than frigid and dry like the rest of Antarctica.

During the summer research season Palmer is home to 44 people, six Snowy Sheathbills, and a half-dozen leopard seals that occasionally bite holes in the Zodiacs. All field research is done in these little rubber boats, buzzing among islands on a gray-black sea and huddling beneath surly clouds.

The penguin team’s schedule has them visiting 21 islands every three days to study penguins, giant-petrels, skuas, gulls, cormorants, and more. Over the course of my stay at Palmer, I hitchhiked with them whenever I could. Donna told me the story of the penguin revolution over visits to four colonies: Torgersen, Biscoe, Humble, and Litchfield.

Adelie Life at Torgersen

The Zodiac’s rubber nose dimpled as it touched the black rock of Torgersen. Donna stepped ashore and in the same motion dropped a ready-made clove hitch around the mooring pin. We handed over the gear: a case of electronics, a radio antenna, a field kit of bands and zip ties, a cattle marker, and an expensive brand of sticky tape.

Donna is intense, brusque, and funny at the same time, like a field-seasoned Bette Midler. She keeps her blond hair tucked behind a Jackson Hole baseball cap, and she wears sunglasses even on cloudy days, as a precaution against indignant seabirds.

At the colony edge, two Brown Skuas were ripping apart the carcass of a penguin chick, now just a spine and two floppy clown feet. Beyond them came the chuntering of about 1,200 Adelies. The reek of penguin urine and dead shrimp combined into a supremely pungent effluent the team calls “guano gravy.” On rainy days the chicks get saturated in it and become some of the sorriest-looking creatures imaginable. On sunny days they sprawl out like beanbag pillows to dry.

An Adelie opened up and disgorged a pink slurry of krill into its youngster’s open mouth. These small, shrimplike crustaceans form the food for almost every Antarctic vertebrate, from penguins to leopard seals to humpback whales. The biologists call it a “krill smoothie,” but it’s not even all that smooth. The black googly eyes looked like poppy seeds in the regurgitated mess.

The field team leader, a wiry biologist named Shawn Farry, grabbed a penguin under the flippers and hauled it into the air like a misbehaving three-year-old. This bird was about to get three expensive devices taped to its back—a satellite tag, a depth recorder, and a radio transmitter. It would wear them for three days as it went about the business of catching krill and feeding its chick.

Data from the transmitters help the researchers track where penguins go to feed, how deeply they dive, and how long they stay out. After three days, the scientists move the devices to a different bird, sampling both gentoos and Adelies. They’ve been using the tags since 2001, and have now recorded data on 50 gentoos and 179 Adelies.

Working quickly, Fraser and field tech Kirstie Yeager taped the three devices securely under the bird’s back feathers. They had premeasured the tape strips and stuck them to a hot water bottle, to keep the adhesive warm. They finished by wrapping zip ties around the whole installation, and then marked the bird temporarily with a green wax cattle marker. When they come looking for it in three days, the radio-transmitter will pinpoint the bird, but a green swipe across the chest makes it a lot easier to spot in a crowd.

Farry let go of the bird, and it scampered back into the penguin scrum.

As we zipped between islands in our skiff, I got an introduction to Antarctic ice in its many forms. Icebergs loomed in the distance, and we began to use them as landmarks. These towering blocks of frozen freshwater break off glaciers and float in the cold sea for months or years until they disintegrate. Penguins sometimes explore icebergs or rest at their bases, but most are too sheer to climb onto.

Periodically our boats ran across lines of brash ice, which is to icebergs what crumbs are to loaves of bread (although these crumbs can be as large as armchairs). The wind and currents push brash ice into impenetrable fields and then disperse it again like a quick change of mind. The chunks are typically too small for penguins to stand on or forage beneath.

A third kind of ice is called sea ice, which forms when the sea surface freezes, rather than from calving glaciers. It’s low, flat, and wide, and during winter so much of it forms that Antarctica doubles in size. Sea ice is the classic habitat of the Adelie Penguin.

Over five weeks we saw enough icebergs to give them names, and we navigated through so much brash ice that it felt like we were floating in a huge glass of Coke. But we didn’t see a single piece of sea ice.

Long-term records show that Palmer Station is now sea-ice-free for 100 days longer each year than 35 years ago. In 1993, the penguin team spent the first part of the season commuting to Torgersen Island on skis, rather than in boats. That doesn’t happen anymore.

If we had seen sea ice, we’d likely have seen many more Adelies on it than gentoos. That’s a basic difference between the two species, and one that I began to appreciate when our team visited Biscoe Point, where both species nest.

Biscoe Point: The Changing of the Guard

At the Biscoe colony, Donna led me along well-trodden penguin pathways, occasionally stepping aside to let mud-stained gentoos shuffle past. Nests were grouped on patches of high, flat ground stained brick red from all the krill in the birds’ diets. These discrete groups of nests are called subcolonies. Because penguins tend to come back to them year after year, they make convenient units for study.

Eventually we reached a group that included a few Adelies—unusual, as the two species tend to nest on separate islands. Donna pulled a clicker out of her pocket and started counting. At 13 islands, the team has made counts like this every year since 1989. To keep from losing track, Donna always counts left to right, going over the adults twice to check her numbers, then taking a third pass to count the chicks.

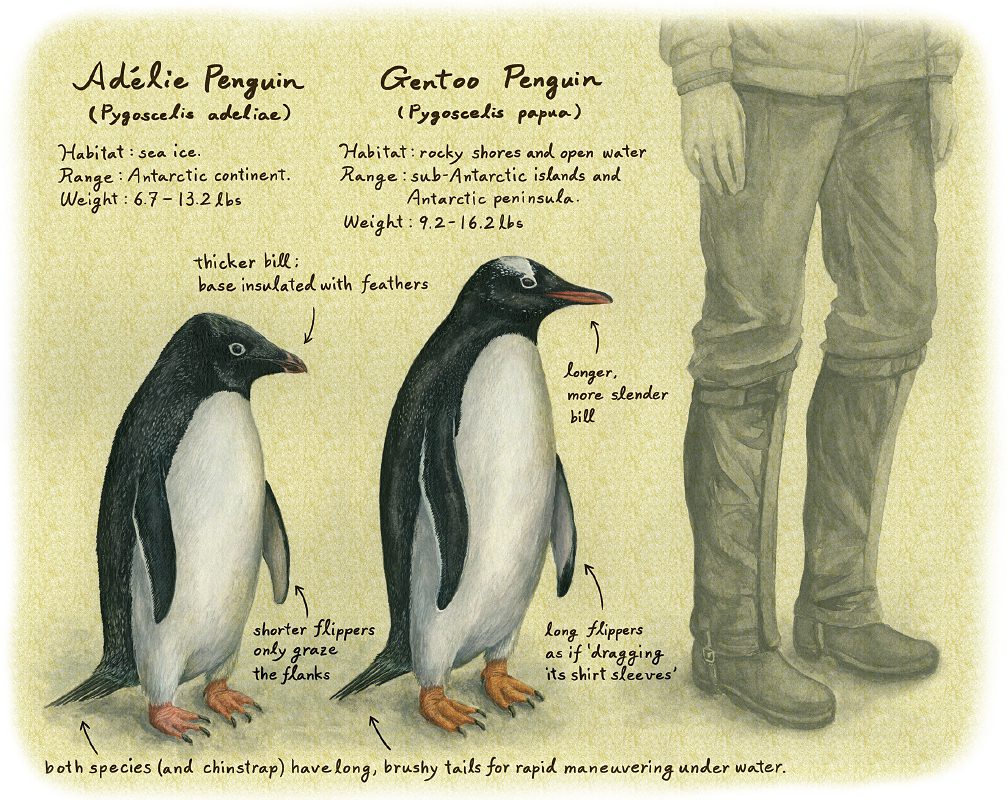

Between clicker flurries she pointed out penguin subtleties—physical differences that cut straight to the heart of why gentoos are increasing and Adelies are not. Gentoos are heavier, taller, and longer-necked than Adelies. When you grab an Adelie by the flippers to put on a tracking device, Yeager told me, its neck is too short for it to nip you. With gentoos you’re not safe. A gentoo’s bill is longer and slimmer, too, and its flippers are so long it seems to be dragging its shirt sleeves in the mud.

Those long flippers and big bodies make gentoos deeper divers. Adelies, in turn, can hold their breath longer and are more suited to foraging beneath sea ice. The team’s tracking data show that gentoos dive as deep as 180 meters, compared to Adelies’ maximum of 100 meters. (Both species’ average dives are much shallower, but the overall pattern remains.) So gentoos thrive in areas where steady currents maintain areas of deep, open water. Adelies look for the opposite: patches of water flecked with sea-ice floes.

Gentoos, like most penguin species, are not truly Antarctic, and they tend to avoid ice. They breed as far north as the Falkland Islands and on other Subantarctic islands in the “furious fifties” latitudes. Only Adelies and emperors have colonized Antarctica proper—an environment ruled by ice.

Adelies have to follow that ice—they’re as migratory as any other bird that chases a seasonal resource. At Palmer, adults migrate southward as soon as they finish breeding, toward whatever sea ice is left at the end of summer. By comparison, gentoos may not migrate at all, choosing instead to keep fishing in the open water around their colonies.

Donna sees this difference in the birds’ temperaments. “Adelies are hard-wired, inflexible, Type A, high stress, highly structured animals,” she said. They arrive at their colonies and immediately set to work. They have about 50 days to raise their chicks from hatching to fledging before a short summer gives way to a punishing winter.

“Gentoos are looser,” Donna said, reflecting the longer summers they evolved with. “There are no right angles in their colonies. They haven’t been to the Martha Stewart section of Staples to get all those organizers.” Adults show up at breeding colonies about two weeks later than Adelies and their chicks take a full month longer to fledge. If a spring snowfall blankets the colony, a gentoo will wait for it to melt. An Adelie will lay its eggs in the snow.

A Contest That’s No Competition

When two closely related species occur together, ecologists tend to look for signs they are competing over resources. But that’s not happening between gentoos and Adelies. “I don’t think there’s even a lick of competition in there,” Donna said.

They’re certainly not competing over nest sites. Adelies are vanishing from colonies on small islands they’ve inhabited for centuries, while gentoos are building a single large colony at Biscoe. And they’re not competing for food, either. They do both eat krill—although so does a healthy population of humpback whales—but tracking data show the two species go to different places and depths to get it.

Palmer is not a battleground where one species is beating out the other; it’s a stage with two separate stories playing on it, both driven by climate change. In the last half-century, Palmer Station’s climate has become steadily less Antarctic and more Subantarctic. The glacier behind Palmer has retreated about 30 feet per year since 1975. It used to be close enough that the station piped in meltwater to drink. Now it’s a quarter-mile away, and the staff drinks desalinated seawater. The penguins, like the humans, are just following the new rules.

“The station hasn’t moved, but somebody new has moved in,” Donna said. “If you envision a band of optimal climate [for Adelies], their optimum has moved south without them.”

The lesson for the rest of the world is one of unintended consequences. The climate is a Rube Goldberg machine: at one end, smokestacks and tailpipes are gushing carbon dioxide, and at the other end a 2-foot-tall army wearing tuxedoes is sweeping down the Antarctic Peninsula. Admittedly, it’s simplistic to label that change as good or bad—Adelies are vanishing around Palmer, but they’re increasing farther south and are still one of the world’s most numerous penguin species.

Nevertheless, the penguin revolution at Palmer is a message: if it’s happening in the most remote, least human-altered continent on earth, it is happening everywhere.

Humble Island: Shifting Baselines

“I’m going to take you to Humble Island,” Donna yelled from the gunwale of the Zodiac. It sounded like some kind of veiled threat until I realized she was pointing at a hump of rock in the distance.

Humble Island is the second largest Adelie colony left in the Palmer region. In mid-January, molting elephant seals lay side by side like rolls of carpet in the middle of the penguins. At any moment, one or a dozen Adelie males would point its bill at the sky and slowly flap its flippers, issuing a harsh rattle. In the distance came the hushed thunder of glaciers calving, pierced by the great farting sounds of sleeping seals. Orange and brown lichens dappled clifftops where giant-petrels nuzzled their solitary chicks.

Donna led me on a census of Humble’s ragtag subcolonies. At Subcolony 5, just 14 adults stood around like it was the waning hours of a cocktail party. I found myself stifling a sense of disappointment. Why had the scientists chosen to study such tiny groups? How could this provide a representative sample?

Donna swept her arm in a broad arc. “See all these little cobbles?” she said. “Those are all Adelie nest stones. There used to be a U-shaped colony all through here; 200-ish nests. It was hard to count, that’s how big it was.”

I had assumed the island had always looked the way it does now. But that’s the difference between visiting a penguin colony once and studying it for 25 years. In the 1970s it had 2,700 nests. Subcolony 5 was one of the few clusters small enough to count accurately. Now Humble has 613 nests total. Ever since, as the party really did wind down for Adelies, the study has become a matter of watching subcolonies wink out of existence.

To an environmental scientist this is an insidious problem known as shifting baselines. If change is happening on the scale of decades, people have trouble recognizing it’s happening at all. It affects our perceptions of everything from fishery catches to songbird declines to the numbers of monarch butterflies and fireflies we see each year. The penguin revolution has happened within the career span of a single Antarctic scientist. But before too long, gentoos will have been at Palmer, and summers will have been ice free, and Adelies will have been scarce, for as long as anyone at the station can remember.

That’s why it’s so important to have scientists collecting ecological data year after year, in a long series of data columns that extend back as far as the first baseline that anyone ever collected.

Return to Litchfield

In late January, Donna took me on a tour of Litchfield Island. It’s a skirt of pebbled beaches surrounding three tall bluffs covered in rare Antarctic mosses. The rocky beaches are still stained faintly pink, and bone fragments—seal and penguin—are mixed with the rocks.

“There were 700 pairs when I got here [in 1991],” Donna said, “The same size as Torgie is now.”

Off to the east lay Christine Island, and beyond that Cormorant Island. These are the next two islands that will lose their Adelies, Donna said, without a trace of uncertainty. On a survey of Christine a few days earlier, as thick snowflakes blew out of a soggy sky, the team had counted 82 adults and just 5 surviving young. In 1989 there had been 1,277 pairs—about the same number now at Torgersen, the biggest remaining colony. “It’s about as bleak as bleak gets,” Donna said.

Just then, I spotted that lone, wide-eyed Adelie picking up a pebble. Who knows what evolutionary imperatives it was obeying in that moment. The bird knew it needed to build a nest out of rocks, but it had not yet figured out it would need a supply of sea ice to fill its chicks’ bellies with krill.

Adelie Penguins are extremely site-faithful. Most return to breed at the exact same subcolony where they hatched as chicks. Perhaps this young bird was one of the last chicks Litchfield ever fledged, eight years ago. To its eyes, did this beach still look like home? Would it be back next year, to gather pebbles and to wait for a mate? I preferred to see the bird as still young and impressionable. Perhaps it will find some sea ice this autumn, fall in with a new group of penguins, and settle somewhere south of here, where prospects for an Adelie are better.

After seeing the changes at Palmer, it hardly makes sense to talk about whether climate change is real. It’s like sitting in a city park on a hot day and debating whether it’s cooler under the shade trees or in the full sun. You can set up thermometers and debate whether they’re properly calibrated. Or you can watch where the picnickers set up their blankets.

“If I give a talk [back home in Montana], I tell people straight up: I’m not here to change your mind, but I will tell you what I see,” Fraser said. That’s the essence of science—the belief that with enough careful observation, the truth will come out into the open.

“Welcome to the future,” she said. “It’s here.”

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library