Facing Into the Wind: The Complicated Fate of the Laysan Albatross

By Hugh Powell

From the Summer 2014 issue of Living Bird magazine.

Laysan Albatross by Hugh Powell September 26, 2014The Laysan Albatross has the lukewarm distinction of being perhaps the least-threatened member of the most-threatened group of birds in the world. Of the world’s 22 albatross species, 15 are vulnerable or endangered, according to the IUCN—but the Laysan is at its highest numbers in a century.

That seems like good news, because if ever a group of animals had the deck stacked against it, it’s the albatrosses. At sea they get caught on industrial fishing hooks and eat plastic by the gulletful. At their nests, introduced predators crack their eggs, eat their chicks, and kill adults. They crisscross international boundaries and economic zones. The ships that mistakenly catch them operate in empty seas where no one is watching. They reproduce slowly and can take decades to build back their numbers after a loss.

Even the Laysan Albatross’s prospects are dimming, it appears, as climate change continues to melt ice and raise sea level. All but a couple thousand of the world’s 600,000 breeding pairs nest on low coral atolls, chiefly Laysan and Midway, in the northwestern Hawaiian Islands. These are likely to start going underwater during this century, according to a recent analysis.

And yet the story of Laysan Albatrosses is also a story of tenacity and triumph. In the last century they have come back from one severe population decline and are rounding the corner on another. Twice they’ve found aid on the coattails of the Endangered Species Act, despite never having been listed themselves. Will we be able to offer them a way through this next setback?

Any solution for these ocean wanderers is going to be complicated, as I discovered on a visit to the island of Kauai, Hawaii. As their remote atoll homes become unsuitable, these long-lived birds will have to find new colony sites and learn how to live near humans. Simultaneously, humans must learn how to keep albatrosses safe on land and at sea.

On Kauai I went albatross banding with Kim Uyehara, a biologist at Kilauea Point National Wildlife Refuge. In no time she had shoved an albatross under my arm, where it sagged like a bag of groceries you know you are destined to drop. I hung on for dear life as it tried to yank its five-inch bill out of my grasp. Its heart thumped against my rib cage, and it gave a deep sigh of resignation as Uyehara put a black band, A081, on its leg. Moments after I released it, the bird unfolded its seven-foot wings and reclaimed its dignity in the air. One enormous white breast feather lay on the ground where it had stood.

These are the complicated fortunes of the Laysan Albatross—a recurring story of people attempting to solve problems that people made. That we keep succeeding, despite the grim predictions, is one of the best arguments for doing conservation I’ve seen yet.

A Rising Tide

The biggest Laysan Albatross colony in the world is at Midway Atoll. I’ve never been there, but Google Maps has—and their Street View feature gives an idea of what a few hundred thousand albatross chicks look like. Big, gawky birds wearing little halos of gray down are everywhere: among the shrubs; lined up in the shade of old military buildings; under the bike racks; scattered across the flat, flat sand.

By comparison the colony at Kilauea Point, Kauai, is one of the world’s smallest, at fewer than 200 nests, but it sits on a clifftop high above the waves. It’s just visible from the lighthouse at the end of the point, where tourists in windbreakers gather to watch breaching humpbacks. Docents point out albatrosses as they sail by at eye level.

When I asked Beth Flint, a supervisory wildlife biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, what she thought was the biggest threat to Laysan Albatrosses, I expected her to say either fishing bycatch or plastics. Instead, she became the first of several biologists I talked to who brought up climate change.

“I don’t hold out much hope for any of those low colonies [such as on Midway and Laysan] that shelter most of the population,” Flint said. “Climate modelers are so careful in how they speak and don’t want to be alarmist, so the story [of sea-level rise] hasn’t been told enough. But unless we can get a lot more high-island colonies up and rolling, their long-term prognosis is not that good.”

Flint referred me to a 2013 U.S. Geological Survey analysis. The report’s key advance was to take the simple “bathtub” effect of rising sea level—gradually making small islands smaller—and add the dynamic effects of wave action. For example, with higher sea levels, more wave energy will reach an atoll’s beaches instead of being stopped by the surrounding coral reef. Seawater will sweep farther into the low, flat interiors of islands, more often. The report concluded that under a modest scenario of 3 feet of sea level rise, the main island at Midway could lose some 65 acres and 70 percent of its current beach.

To Flint, a series of disasters in 2011 amply illustrated the dangers. That year, two particularly large winter storms hit Midway and washed away some 10,000 eggs. A few weeks later, on March 11, the tsunami from the devastating Tohoku earthquake in Japan reached Midway. “That gave us a little foreshadowing into the future,” she told me.

The tsunami arrived in the middle of the night, according to Pete Leary, Midway’s refuge biologist at the time. Everyone had retreated to the third floor of a building in the center of the main island. When it came, the five-foot tsunami was powerful enough to wash over about one-third of their island and two-thirds of Midway’s other main island.

The water looked surreally calm the next morning, Leary recalled. “It was like glass. All the water that had washed up on land was evaporating, so it was really misty, really foggy. There were dead birds everywhere.”

Many chicks and adults had been swept off their nests or out to sea. The water had picked up debris from the island—twigs, branches, washed-up fishing floats, pieces of pier—and deposited it in ridges hundreds of feet long and up to three feet high. Chicks and adults were buried up to their necks.

“Sometimes we’d dig out one chick and then see some little feet kicking underneath and we’d dig a little further and pull out one that had been completely buried,” Leary said. “We were trying to save everybody we could. At least five days later we were still digging birds out of the debris lines.”

A U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service briefing estimated the toll from the tsunami at 212,000 chicks on Midway, plus another 42,000 killed on the other Hawaiian atolls. Because chicks don’t return to breed until about age five, this missing quarter of a million won’t be evident at Midway for another couple of years. Though the disaster was caused by an earthquake and not climate change, Flint sees it as a preview for when storms begin blowing in over elevated sea levels.

This is why I was fascinated by my visit to Kauai. The albatrosses I saw there—treading on ironwood needles at Kilauea Point, roaming the cul-de-sacs of Princeville, even the two adults and chick on the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Kauai albatross cam—represent less than 0.1 percent of today’s Laysan Albatrosses. But they are also a glimpse of the future.

Living with Humans

An albatross colony can survive even a quarter of a million chick deaths in one blow if it’s a rare event. But if high seas begin to wash over the atolls regularly, those colonies will dwindle away. By contrast, the albatross nests at Kilauea Point are a good 200 feet or more above the surf. Another small colony on Kaena Point, Oahu, sits safely on a sandy plain above dark shelves of lava. Biologists such as Flint and Lindsay Young, of Pacific Rim Conservation, on Oahu, envision an eventual wholesale transition: remnant colonies in the centers of a few of the low atolls, large colonies on the larger islands.

Most people don’t think about climate change as a problem for Laysan Albatrosses, Young told me. “They ask if they’re endangered and we say no, but in 50 years we don’t know. That’s why we’re protecting all these high island colonies on Kauai and Oahu.”

While such a transition would solve the problem of flooding, it will usher in a suite of new problems associated with living near humans. The biggest of these are the animals that associate with us and the tangles of land-use issues that govern how we share the land. Both problems are already evident at Kilauea Point.

By and large, Midway, Laysan, and the other atolls don’t have land-based predators—that’s why so many seabirds nest there. But on the main Hawaiian Islands humans have brought pigs, dogs, cats, mice, rats, and mongooses. For albatrosses, the main problem is free-roaming dogs, which can make short work of a colony. In the 2013–14 breeding season on Kauai, dogs killed at least 28 adult albatrosses on their nests, according to the Kauai Albatross Network. (Cats and mongooses pose real threats as well.)

“You’re going to have to trap [predators] no matter what. That’s just part of the deal,” said Young about the prospect of colonies surviving on Hawaii’s main islands. She has already overseen the installation of a predator-proof fence at Oahu’s Kaena Point and documented its performance (effective but costly). Another is planned for Kilauea Point in 2015.

Compared with the direct toll of predation, the other problem—fitting in around human land uses—seems less pressing but is harder to fix. Even for a species like an albatross, which inspires goodwill and compassion in just about anyone who sees one, conflicting priorities can wind up tying the hands of land managers. On a visit to the Navy’s Pacific Missile Range Facility, I saw this first hand.

I drove from Kilauea Point to the other side of Kauai to meet Tom Savre, biologist for the missile range. He’s a career birder and a civilian, with the wiry frame and faded t-shirt of an ultimate Frisbee player. He took me on a driving tour to show me the Navy’s plan to keep albatrosses from becoming aviation hazards.

This part of Savre’s job sounds like it sprang from the pages of Catch-22. Each year, about 80 pairs of Laysan Albatrosses try to breed on the Navy’s airfields. Savre has to make sure that they don’t, either by hazing them or by removing their eggs so that their nests fail. (The Navy has legal authority to shoot albatrosses but has never used it.)

Alas, albatrosses are long-lived and stubborn. Year after year, despite perpetual disappointment, the birds return. Some have been trying to nest there for decades.

Reluctant to let confiscated eggs go to waste each year, the Navy has teamed up with Lindsay Young to donate eggs to civilian albatrosses. Savre stores the eggs in an incubator in a prefab office building near the runway. When Young locates an albatross on the north shore that has laid an infertile egg, she drives up with a healthy military egg. She kneels down before the incubating bird, blocks its view with her clipboard, and pulls a quick switcheroo.

On the face of it, the egg swap is a win-win-win. An albatross gets a second try at raising young; an egg from the missile range has a chance to become a chick; and in time there should be fewer albatrosses on military land and more on the north shore. But that’s where the land-use issues come in.

On Kauai, albatrosses nest on private land, state land, federal land, and military land. The military can’t allow the birds on their airfields. The state is leery of allowing them on unfenced land, even private land, because of the very real danger of dogs. Some federal biologists question the advisability of giving a fertile egg to an albatross that just laid an infertile egg, since that may indicate that the bird is not in chick-rearing condition.

Most of the egg swaps used to happen on federal land, at Kilauea Point. But the refuge is in the middle of a multiyear avian botulism outbreak that is killing off several critically endangered Hawaiian waterbirds. The first time I got through to Kim Uyehara she was standing in a flooded taro field looking for dead Hawaiian Ducks. With Laysan Albatross numbers growing on their own, the egg swap program has taken a back seat.

This year, Savre and Young were unable to secure any permits to swap eggs on Kauai. Not to be put off, Young told me that next year they have funding to begin translocating eggs to Oahu, where she will hand-raise them and attempt to start a new colony from scratch on James Campbell National Wildlife Refuge. It’s one more step in shifting albatrosses from low atolls to high islands.

Track Record of Tenacity

So far, it looks like sea-level rise is going to drown the current colonies, and land-use wrangles and predation are going to take down the colonies of the future. So where exactly is the hope for Laysan Albatrosses? It resides in three unlikely sounding stories: feather hunting, fishing bycatch, and plastics.

The feather trade almost put an end to Laysan Albatrosses right at the start of the 20th century. In 1902, Japanese feather hunters began a wholesale destruction of Hawaiian seabird colonies to supply Western hat-makers. By the time feather hunting was banned in 1922, only an estimated 18,000 Laysan Albatross pairs were left in the world. (There had been an estimated half-million pairs on Laysan Island alone.) Their numbers began to improve—remarkably quickly for a bird saddled with a low reproductive rate. They reached 280,000 pairs in 1958 and have doubled again since then.

The next obstacle the 20th century had in store was industrial fishing—but it’s also a conservation success story in progress. Two kinds of fishing are particularly bad for albatrosses: drift nets that cover large expanses of surface water and longline rigs, which are used to catch many of our favorite seafoods: tuna, haddock, cod, swordfish, and Chilean sea bass, to name a few. The ships use lines up to 60 miles long.

As the global appetite for seafood increased, so did the scale of the problem. In 1991, an Australian biologist estimated that Japanese longline tuna fleets were setting 108 million hooks and killing a staggering 44,000 albatrosses per year. Drift nets placed in the high seas were killing as many as 27,500 albatrosses per year in the North Pacific alone.

The numbers were so unsettling that action was swift. Drift netting was banned in 1992 by international agreement (it still goes on in some national waters), and people started looking for ways to reduce longline bycatch.

To do this, biologists worked with fishermen. They needed methods that were straightforward, inexpensive, and didn’t reduce the fish catch. Fortunately, the industry was motivated.

“If you lose a lot of bait to birds, you don’t catch a lot of fish,” said Ed Melvin, who studies bycatch at the University of Washington. “So the motivation is there at two levels. Fishermen say albatrosses are the souls of fishermen. So I’m really optimistic that if we can come up with practical tools, they’re going to be used.”

In Alaska and Hawaii, fishing fleets were also motivated by the Endangered Species Act, which protected Short-tailed Albatrosses and green sea turtles. Ships that didn’t avoid bycatch could have their season shut down. Laysan Albatrosses benefited by extension.

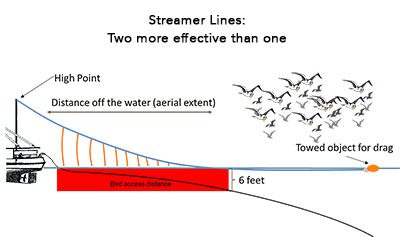

In the end, three fairly simple measures turned out to be about 90 percent effective when used together: First, hang gaudy streamer lines behind the ship to scare birds away from baited hooks until they sink out of view. Second, weight the baited lines so they sink faster. Third, bait the hooks at night, when most seabirds are less active.

Of course, finding the answer is not quite the same thing as solving the problem. Fisheries use many different kinds of gear; fishermen speak many different languages; regulations and oversight are slow to be enacted.

But when drift nets were banned, bycatch of Laysan Albatrosses dropped from a high of around 30,000 per year to about 3,000 per year. When the Hawaiian tuna fleet adopted longline measures, it dropped again, from 1,500 per year to 100 per year. Bycatch is still regarded as one of the primary threats to albatrosses and petrels, but at least we’re not still searching for the way to fix it.

In the late 20th century emerged the problem of the “Great Pacific Garbage Patch”—the detritus of modern life that accumulates in the centers of ocean gyres. By one estimate, Laysan Albatrosses cumulatively feed five tons of plastic each year to their chicks. Kaloakulua, the chick on the Cornell Lab’s 2014 albatross cam, had plastic in her stomach by the time she was 4 months old.

Sometimes the animal you’re trying to save can surprise you, though. Plastics are less dangerous to albatrosses than has been suggested, Flint told me.

“They don’t eat plastics by mistake,” Flint said, “They seek them out and swallow them on purpose because they’re a substrate for flying fish eggs. If you walked around an albatross colony in the 1950s, you would find albatross carcasses full of pumice and sticks and wood.

“They’ve been eating natural plastics all their life,” she said, referring to the hard, sharp beaks of squid that are the albatrosses’ main food. Flint stressed that plastics do pose problems: they harm species lower on the food chain. They also accumulate toxins from the water and can pose a chemical threat when swallowed. But they do not necessarily cause albatross chicks to starve. Before fledging, most albatross chicks cough up plastic and squid beaks alike to clear their stomach before taking their first flight. Kaloakulua successfully regurgitated her “bolus” of stomach contents on June 1, 2014. The following video shows a Kauai Albatross Network volunteer examining the plastic that it contained:

What You Can Do

Looking Forward

It’s been said that the number one job requirement for a conservation biologist is relentless optimism. Laysan Albatrosses have faced one dreadful obstacle after another. Turning the feather trade around required changing fashion. Solving longline bycatch means asking fishermen to change the way they fish. And yet it’s working—how’s that for optimism?

Sea-level rise and climate change are perhaps the biggest problems yet. The adversary is the energy source that underpins modern society, and it remains to be seen what any of us can do. We may find an alternative energy source, or we may just learn how to move albatross colonies. It will probably require more imagination than it took to develop the featherless hat. But at least imagination and dedication are qualities we have in abundance.

This is where I take inspiration from the albatross, which shows such grace in its mastery of the elements. Each time we have attempted to address a problem, they have met us halfway. I stood above the surf at Kilauea Point and watched albatross A081 peeling ribbons off the wind. Its long, stiff wings curved like blades of grass, and every swoop and rise was the result of imperceptible motions of its wing tips. This is a bird for which storms are opportunity and still air is an obstruction, I thought. There is no serenity as absolute as an albatross facing into the wind.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library