Gardening for Cassowaries

By Hugh Powell

April 15, 2013

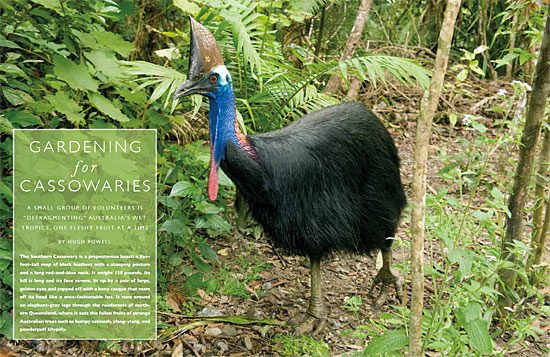

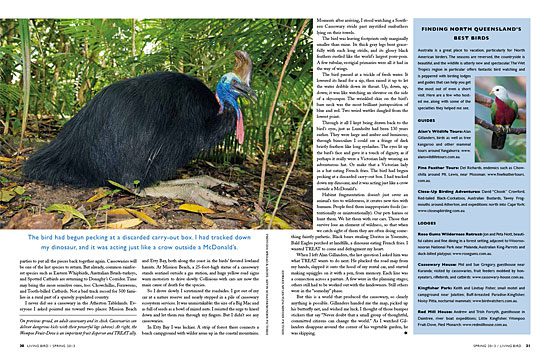

The Southern Cassowary is a preposterous beast: a five-foot-tall mop of black feathers with a stooping posture and a long red-and-blue neck. It weighs 150 pounds. Its bill is long and its face severe, lit up by a pair of large, golden eyes and topped off with a bony casque that rears off its head like a once-fashionable hat. It runs around on elephant-gray legs through the rainforests of northern Queensland, where it eats the fallen fruits of strange Australian trees such as bumpy satinash, ylang-ylang, and powderpuff lillypilly.

In 1881, a Norwegian naturalist named Carl Lumholtz called the cassowary Australia’s noblest and stateliest bird. “Its eyes, which cannot fail to be admired, form the most beautiful feature of the cassowary,” he wrote. “Their expression is defiant and proud, as that of the eagle’s eyes.” And yet plantation owners were already using cassowary skins as rugs and doormats. The forest cassowary, he wrote, “will doubtless become extinct as civilization gradually advances and clears the scrubs.”

For all of these reasons, I never wanted to see a cassowary in the same way I wanted to see a kookaburra or a Wompoo Fruit- Dove. It was more like the way I wanted to see a brontosaurus.

Despite Lumholtz’s gloomy prediction, Southern Cassowaries aren’t extinct just yet. They are endangered, though; fewer than 1,500 are thought to remain in Australia. And the clearing of “the scrubs”—Australian for rainforest—has indeed proven to be its chief enemy. Eighty percent of lowland rainforests in Australia’s Wet Tropics region—the cassowary’s stronghold—have been cleared.

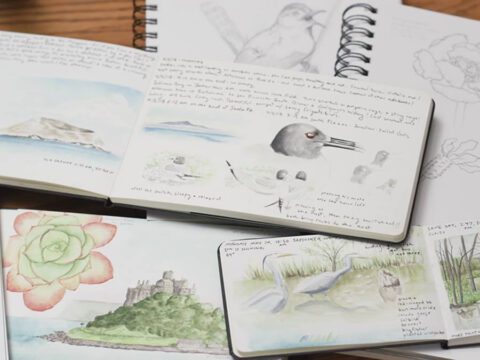

Habitat fragmentation is the flip side of human population growth, which makes it one of the most vexing conservation problems in the world. So I was cheered to learn that a small group in north Queensland has begun to “defragment” the landscape around them. Trees for the Evelyn and Atherton Tablelands (TREAT) operates largely on volunteer labor, a partnership with the Queensland government, and annual dues of just $15. Over the last 30 years, they have pioneered methods of gathering, propagating, and replanting local rainforest trees. Working out techniques at a tiny nursery tucked into a nearby park, its members have rethought basic approaches to reforestation and then proven them in a series of successful plantings. Their slogan: the right tree in the right place for the right reason.

TREAT’s headquarters lie at the western edge of the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area, on a fertile volcanic plateau known as the Atherton Tablelands. A trio of quiet, pretty towns named Atherton, Malanda, and Yungaburra thrive in the tropical climate. Bakeries sell steak-and-mushy-pea pies for lunch. Cows and barns dot the rolling hills, and platypuses paddle through farmers’ stock ponds.

They get about 10 feet of rain every year. Fingers of wet forest climb from the pastures into mist-cloaked highlands to the east. There, Victoria’s Riflebirds screech and fan their velvet-black wings. Tooth-billed Catbirds, the most reserved of the bowerbirds, decorate the forest floor with leaves turned pale side up. And somewhere, a few cassowaries still slip their five-foot frames between tangled vines, invisible as rails in a salt marsh.

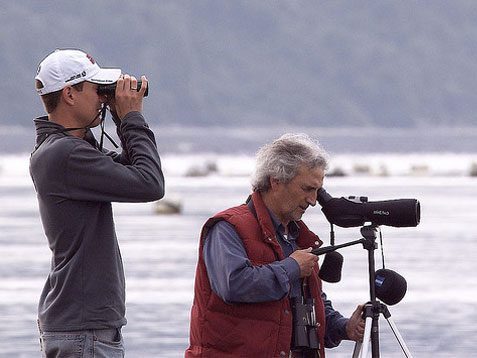

The first TREAT member I met was a naturalist and guide named Alan Gillanders. We started the day at Mount Hypipamee National Park, where lush ferns drip down the steep slopes of a volcanic crater. An entrance sign gave tips on what to do in case of cassowary attack.

Gillanders led us to the bower of a Golden Bowerbird. It was a chest-high pile of twisted twigs that had been stuck together by threads of fungus. Soon the bird appeared, as lustrous as gold in the dim understory. It opened its bill and made a sound like a dollar bill getting sucked into a vending machine.

Gillanders must be about 50, but he has a boyish aspect accentuated by a quick, slightly gap-toothed smile and wavy black hair. He overflows, head-of-the-class style, with local natural history: the name of the bowerbird fungus; the proper way to flick a leech off your leg.

Sign or no sign, Gillanders put our chances of seeing a cassowary here at about 3 percent. Mount Hypipamee is one of an estimated 10,000 forest fragments in the Wet Tropics, separated from the heart of the reserve by miles of pasture and field. Though the vegetation looks healthy, many larger animals can’t survive in such small spaces. Individuals that do persist are cut off from larger populations and become vulnerable to inbreeding or disease. Cassowaries, which need about seven square kilometers to live in, are the first to go, but they are by no means the only ones.

Work by tropical ecologist William Laurance in the 1980s traced the decline of several endemic marsupials, such as the spotted-tailed quoll, the surprisingly cute musky rat-kangaroo, and the gentle Lumholtz’s tree-kangaroo. As each of these species goes, their links to their habitat—what ecologists call “ecosystem services”—are severed as well.

TREAT’s answer to this problem is to steadily reconnect forests by planting trees along streams and other natural corridors. It’s an unusual approach for a community project, because it doesn’t yield showpiece properties such as a refuge or a park. Most work occurs on private lands that may not even be visible from a public road. But the payoff is mathematical: plant a small strip of land that links two fragments together, and they add up to a much larger piece of functional forest than could ever have been planted from scratch.

TREAT started life in 1982 when two biologists, Geoff Tracey and Joan Wright, called the first meeting to order in the Yungaburra pub. At the time, only one small nursery in the region offered local, native plants for gardening; everything else on the market was exotic. “The fellow there used to give away the local plants,” Gillanders recalled, “because he didn’t know enough about their horticultural potential” to feel good about selling them.

Tracey and Wright knew they had to change this. Australia is a unique continent, and the Wet Tropics are a unique part of it. More than 40 percent of Australia’s bird species occur here, in just a quarter of 1 percent of Australia’s total land area. Some 700 plant species occur nowhere else. If the goal is to retain the region’s characteristic habitats, then working with exotic species is simply not an option.

Tracey had a friend in the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service named Peter Stanton. He was a sympathetic ear; as a rainforest ecologist, he had invented the standard classification system for Australian rainforests. Stanton set up a partnership with TREAT that allowed members to legally collect rainforest fruits from nearby parks. He also found funding for a small nursery at nearby Lake Eacham National Park, and for a part-time manager to run it.

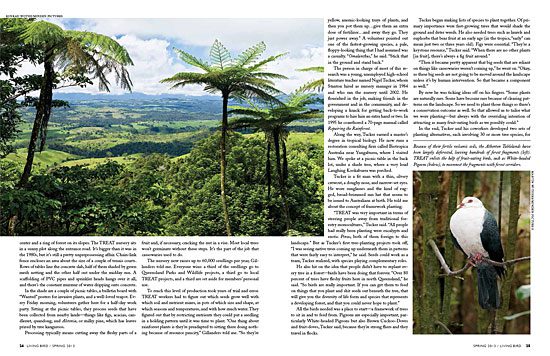

Lake Eacham is an old volcanic crater with a pretty lake in the center and a ring of forest on its slopes. The TREAT nursery sits in a sunny plot along the entrance road. It’s bigger than it was in the 1980s, but it’s still a pretty unprepossessing affair. Chain-link fence encloses an area about the size of a couple of tennis courts. Rows of tables line the concrete slab, half of them shaded by green mesh netting and the other half out under the midday sun. A scaffolding of PVC pipes and sprinkler heads hangs over it all, and there’s the constant murmur of water dripping onto concrete.

In the shade are a couple of picnic tables, a bulletin board with “Wanted” posters for invasive plants, and a well-loved teapot. Every Friday morning, volunteers gather here for a half-day work party. Sitting at the picnic tables, they process seeds that have been collected from nearby lands—things like figs, acacias, candlenut, quandong, and Alstonia, or milky pine, which has leaves prized by tree kangaroos.

Processing typically means cutting away the fleshy parts of a fruit and, if necessary, cracking the nut in a vise. Most local trees won’t germinate without these steps. It’s the part of the job that cassowaries used to do.

The nursery now raises up to 60,000 seedlings per year, Gillanders told me. Everyone wins: a third of the seedlings go to Queensland Parks and Wildlife projects, a third go to local TREAT projects, and a third are set aside for members’ personal use.

To reach this level of production took years of trial and error. TREAT workers had to figure out which seeds grow well with which soil and nutrient mixes, in pots of which size and shape, at which seasons and temperatures, and with how much water. They figured out that by restricting nutrients they could put a seedling in a holding pattern until it was time to plant. “One thing about rainforest plants is they’re preadapted to sitting there doing nothing because of resource paucity,” Gillanders told me. “So they’re yellow, anemic-looking trays of plants, and then you pot them up…give them an extra dose of fertilizer…and away they go. They just power away.” A volunteer pointed out one of the fastest-growing species, a pale, floppy-looking thing that I had assumed was a casualty. “Omalanthus,” he said. “Stick that in the ground and stand back.”

The person in charge of most of this research was a young, unemployed high-school literature teacher named Nigel Tucker, whom Stanton hired as nursery manager in 1984 and who ran the nursery until 2002. He flourished in the job, making friends in the government and in the community, and developing a knack for getting back-to-work programs to hire him an extra hand or two. In 1995 he coauthored a 70-page manual called Repairing the Rainforest.

Along the way, Tucker earned a master’s degree in tropical biology. He now runs a restoration consulting firm called Biotropica Australia near Yungaburra, where I visited him. We spoke at a picnic table in the back lot, under a shade tree, where a very loud Laughing Kookaburra was perched.

Tucker is a fit man with a thin, silvery crewcut, a doughy nose, and narrow-set eyes. He wore sunglasses and the kind of rugged, broad-brimmed sun hat that seems to be issued to Australians at birth. He told me about the concept of framework planting.

“TREAT was very important in terms of steering people away from traditional forestry monocultures,” Tucker said. “All people had really been planting were eucalypts and exotic Pinus, both of them foreign to this landscape.” But as Tucker’s first tree-planting projects took off, “I was seeing native trees coming up underneath them in patterns that were fairly easy to interpret,” he said. Seeds could work as a team, Tucker realized, with species playing complementary roles.

He also hit on the idea that people didn’t have to replant every tree in a forest—birds have been doing that forever. “Over 80 percent of trees have fleshy fruits here in north Queensland,” he said. “So birds are really important. If you can get them to feed on things that you plant and shit seeds out beneath the tree, that will give you the diversity of life form and species that represents a developing forest, and that you could never hope to plant.”

All the birds needed was a place to start—a framework of trees to sit in and to feed from. Pigeons are especially important, particularly White-headed Pigeons but also Brown Cuckoo-Doves and fruit-doves, Tucker said, because they’re strong fliers and they travel in flocks.

Tucker began making lists of species to plant together. Of primary importance were fast-growing trees that would shade the ground and deter weeds. He also needed trees such as laurels and euphorbs that bear fruit at an early age (in the tropics, “early” can mean just two or three years old). Figs were essential. “They’re a keystone resource,” Tucker said. “When there are no other plants [in fruit], there’s always a fig fruit around.”

“Then it became pretty apparent that big seeds that are reliant on things like cassowaries weren’t coming up,” he went on. “Okay, so these big seeds are not going to be moved around the landscape unless it’s by human intervention. So that became a component as well.”

By now he was ticking ideas off on his fingers. “Some plants are naturally rare. Some have become rare because of clearing patterns on the landscape. So we need to plant those things so there’s a conservation outcome as well. So that allowed us to tailor what we were planting—but always with the overriding intention of attracting as many fruit-eating birds as we possibly could.”

In the end, Tucker and his coworkers developed two sets of planting alternatives, each involving 30 or more tree species, for each of the 12 major rainforest types in north Queensland. They take up 21 pages in the back of Repairing the Rainforest.

One of his early successes was called Donaghy’s Corridor. From 1995 to 1998, TREAT volunteers convened in a pasture owned by John Donaghy. It had been cleared since the 1930s, and their goal was to reforest a 100-meter-wide strip along three-quarters of a mile of stream. Once it grew back, it would link together tiny Lake Barrine National Park with 200,000-acre Wooroonooran National Park to the east.

With 200 volunteers pitching in, the planting took a total of just four days. (Gathering, germinating, and growing the seedlings is slower.) Some 18,000 seedlings went into the ground representing 103 tree species.

Surveys conducted three years after planting detected more than 4,000 new seedlings and 119 species just on the sampling transects, and 35 species were new to the project—brought in by birds. Only 10 years after planting, the canopy was more than 60 feet high. Over the years, TREAT has had similar successes with six other major projects in the region.

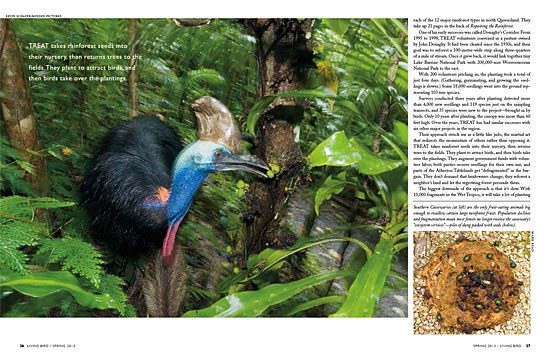

Their approach struck me as a little like judo, the martial art that redirects the momentum of others rather than opposing it. TREAT takes rainforest seeds into their nursery, then returns trees to the fields. They plant to attract birds, and then birds take over the plantings. They augment government funds with volunteer labor; both parties receive seedlings for their own use, and parts of the Atherton Tablelands get “defragmented” in the bargain. They don’t demand that landowners change; they reforest a neighbor’s land and let the regrowing forest persuade them.

The biggest downside of the approach is that it’s slow. With 10,000 fragments in the Wet Tropics, it will take a lot of planting parties to put all the pieces back together again. Cassowaries will be one of the last species to return. But already, common rainforest species such as Eastern Whipbirds, Australian Brush-turkeys, and Spotted Catbirds are returning to Donaghy’s Corridor. Time may bring the more sensitive ones, too: Chowchillas, Fernwrens, and Tooth-billed Catbirds. Not a bad track record for 500 families in a rural part of a sparsely populated country.

I never did see a cassowary in the Atherton Tablelands. Everyone I asked pointed me toward two places: Mission Beach and Etty Bay, both along the coast in the birds’ favored lowland haunts. At Mission Beach, a 25-foot-high statue of a cassowary stands sentinel outside a gas station, and huge yellow road signs warn motorists to drive slowly. Collisions with cars are now the main cause of death for the species.

So I drove slowly. I scrutinized the roadsides. I got out of my car at a nature reserve and nearly stepped in a pile of cassowary ecosystem services. It was unmistakable: the size of a Big Mac and as full of seeds as a bowl of mixed nuts. I resisted the urge to kneel down and let them run through my fingers. But I didn’t see any cassowaries.

In Etty Bay I was luckier. A strip of forest there connects a beach campground with wilder areas up in the coastal mountains. Moments after arriving, I stood watching a Southern Cassowary stride past mystified sunbathers lying on their towels.

The bird was leaving footprints only marginally smaller than mine. Its thick gray legs bent gracefully with each long stride, and its glossy black feathers rustled like the world’s largest pom-pom. A few tubular, vestigial primaries were all it had in the way of wings.

The bird paused at a trickle of fresh water. It lowered its head for a sip, then raised it up to let the water dribble down its throat. Up, down, up, down; it was like watching an elevator on the side of a skyscraper. The wrinkled skin on the bird’s bare neck was the most brilliant juxtaposition of blue and red. Two weird wattles dangled from the lowest point.

Through it all I kept being drawn back to the bird’s eyes, just as Lumholtz had been 130 years earlier. They were large and amber and luminous; through binoculars I could see a fringe of dark bristly feathers like long eyelashes. The eyes lit up the bird’s face and gave it a touch of dignity, as if perhaps it really were a Victorian lady wearing an adventurous hat. Or make that a Victorian lady in a hat eating French fries. The bird had begun pecking at a discarded carry-out box. I had tracked down my dinosaur, and it was acting just like a crow outside a McDonald’s.

Habitat fragmentation doesn’t just sever an animal’s ties to wilderness, it creates new ties with humans. People feed them inappropriate foods (intentionally or unintentionally). Our pets harass or hunt them. We hit them with our cars. Those that survive lose an element of wildness, so that when we catch sight of them they are often doing something faintly pathetic. Black bears stealing Doritos in Yosemite, Bald Eagles perched at landfills, a dinosaur eating French fries. I wanted TREAT to come and defragment my heart.

When I left Alan Gillanders, the last question I asked him was what TREAT wants to do next. He plucked the road map from my hands, slapped it onto the hood of my rental car, and started making squiggles on it with a pen, from memory. Each line was a connection across a pasture. A few were in the planning stages; others still had to be worked out with the landowners. Still others were in the “someday” phase.

But this is a world that produced the cassowary, so clearly anything is possible. Gillanders handed me the map, picked up his butterfly net, and wished me luck. I thought of those bumper stickers that say “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world.” As I watched Gillanders disappear around the corner of his vegetable garden, he was skipping.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library

Don't miss a thing! Join our email list

The Cornell Lab will send you updates about birds,

birding, and opportunities to help bird conservation.