Dinner Guests: How Wolves and Ravens Coexist at Kills

By Gustave Axelson; Photograph by Jim Brandenburg/Minden Pictures

April 15, 2012

It was a mystery that had long nagged wolf researchers, a math problem that didn’t add up: based on per-capita meat acquisition from killing large prey, wolves would get the most meat if they hunted in pairs. And yet, wolves tend to hunt in packs of four or more.

Even taking into account the more frequent kill rate of a larger pack, a wolf duo should still get more meat, because they don’t have to share with as many other wolves. But nearly everything in nature happens for a reason, including wolf pack formation. The challenge for scientists was to figure out why.

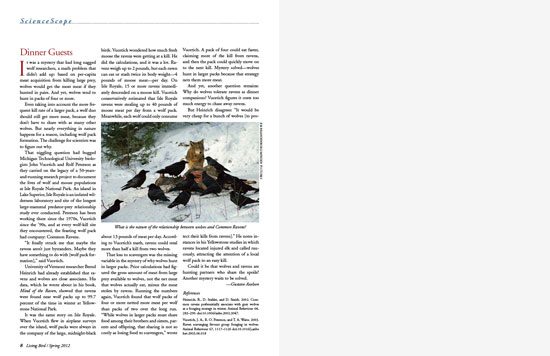

That niggling question had bugged Michigan Technological University biologists John Vucetich and Rolf Peterson as they carried on the legacy of a 50-years-and-running research project to document the lives of wolf and moose populations at Isle Royale National Park. An island in Lake Superior, Isle Royale is an isolated wilderness laboratory and site of the longest large-mammal predator-prey relationship study ever conducted. Peterson has been working there since the 1970s, Vucetich since the ’90s, and at every wolf-kill site they encountered, the feasting wolf pack had company: Common Ravens.

“It finally struck me that maybe the ravens aren’t just bystanders. Maybe they have something to do with [wolf pack formation],” said Vucetich.

University of Vermont researcher Bernd Heinrich had already established that ravens and wolves are close associates. His data, which he wrote about in his book, Mind of the Raven, showed that ravens were found near wolf packs up to 99.7 percent of the time in winter at Yellowstone National Park.

It was the same story on Isle Royale. When Vucetich flew in airplane surveys over the island, wolf packs were always in the company of the large, midnight-black birds. Vucetich wondered how much fresh moose the ravens were getting at a kill. He did the calculations, and it was a lot. Ravens weigh up to 2 pounds, but each raven can eat or stash twice its body weight—4 pounds of moose meat—per day. On Isle Royale, 15 or more ravens immediately descended on a moose kill. Vucetich conservatively estimated that Isle Royale ravens were stealing up to 40 pounds of moose meat per day from a wolf pack. Meanwhile, each wolf could only consume about 13 pounds of meat per day. According to Vucetich’s math, ravens could steal more than half a kill from two wolves.

That loss to scavengers was the missing variable in the mystery of why wolves hunt in larger packs. Prior calculations had figured the gross amount of meat from large prey available to wolves, not the net meat that wolves actually eat, minus the meat stolen by ravens. Running the numbers again, Vucetich found that wolf packs of four or more netted more meat per wolf than packs of two over the long run. “While wolves in larger packs must share food among their brothers and sisters, parents and offspring, that sharing is not so costly as losing food to scavengers,” wrote Vucetich. A pack of four could eat faster, claiming more of the kill from ravens, and then the pack could quickly move on to the next kill. Mystery solved—wolves hunt in larger packs because that strategy nets them more meat.

And yet, another question remains: Why do wolves tolerate ravens as dinner companions? Vucetich figures it costs too much energy to chase away ravens. But Heinrich disagrees: “It would be very cheap for a bunch of wolves [to protect their kills from ravens].” He notes instances in his Yellowstone studies in which ravens located injured elk and called raucously, attracting the attention of a local wolf pack to an easy kill.

Could it be that wolves and ravens are hunting partners who share the spoils? Another mystery waits to be solved.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library