Return to Durango: Searching for Mexico’s Imperial Woodpecker

By Tim Gallagher

October 15, 2011

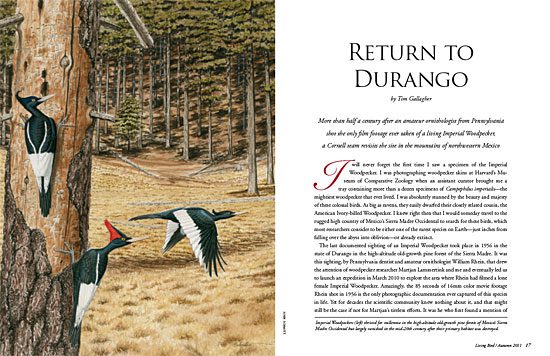

I will never forget the first time I saw a specimen of the Imperial Woodpecker. I was photographing woodpecker skins at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology when an assistant curator brought me a tray containing more than a dozen specimens of Campephilus imperialis—the mightiest woodpecker that ever lived. I was absolutely stunned by the beauty and majesty of these colossal birds. As big as ravens, they easily dwarfed their closely related cousin, the American Ivory-billed Woodpecker. I knew right then that I would someday travel to the rugged high country of Mexico’s Sierra Madre Occidental to search for these birds, which most researchers consider to be either one of the rarest species on Earth—just inches from falling over the abyss into oblivion—or already extinct.

The last documented sighting of an Imperial Woodpecker took place in 1956 in the state of Durango in the high-altitude old-growth pine forest of the Sierra Madre. It was this sighting, by Pennsylvania dentist and amateur ornithologist William Rhein, that drew the attention of woodpecker researcher Martjan Lammertink and me and eventually led us to launch an expedition in March 2010 to explore the area where Rhein had filmed a lone female Imperial Woodpecker. Amazingly, the 85 seconds of 16mm color movie footage Rhein shot in 1956 is the only photographic documentation ever captured of this species in life. Yet for decades the scientific community knew nothing about it, and that might still be the case if not for Martjan’s tireless efforts. It was he who first found a mention of the film while reading through a 1962 letter in James Tanner’s personal correspondence, archived at Cornell University.

Tanner was well known for his exhaustive studies of a small population of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers in Louisiana in the 1930s, but he also looked for Imperial Woodpeckers in Mexico for several weeks in 1962. While planning his expedition, he wrote to William Rhein and asked about the imperials he had encountered there in the 1950s. In one of the letters Rhein wrote back to Tanner he mentioned a film he had shot, which included “some very poor footage of a female ivory-billed with several short flight shots taken hand held from the back of a mule.” (These birds were often referred to as Imperial “Ivory-billed” Woodpeckers at that time.) Martjan was shocked to read this. As far as anyone knew, no one had ever filmed or photographed a living Imperial Woodpecker, and he was determined to locate and view the film.

Martjan had been fascinated by Campephilus woodpeckers since childhood—especially the largest of them, the Ivory-billed and Imperial woodpeckers. While still in his teens, he traveled to Cuba at his own expense (using money he’d saved from working at a dairy factory in the Netherlands) and launched an expedition to search the forests of the island for Ivory-billed Woodpeckers. A few years later, in the mid-1990s, he headed to the mountains of Mexico to look for the Imperial Woodpecker and completed an exhaustive months-long search through remnants of old-growth pine forest that had escaped logging. Although he didn’t find any of the birds, he did interview a number of mountain residents who told him compelling stories of lone Imperial Woodpeckers that apparently survived into the 1990s.

It was not until he returned to his home in the Netherlands that Martjan read Rhein’s letter and learned of the Imperial Woodpecker footage. He immediately started trying to contact him. Unfortunately, Rhein proved to be as difficult to locate as a rare bird. Then in his late 80s, Rhein had retired from dentistry years earlier and moved away from his home in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, without leaving a forwarding address. Martjan had written to his old address and the current resident told him he thought Rhein might have moved to Mechanicsburg, about a dozen miles away, but Martjan couldn’t find a listing for him. He then contacted a person at the local Audubon chapter, who said he knew Rhein but that he had become reclusive, so he was reluctant to give him his address or phone number.

This was more than Martjan could stand, so the next time he traveled to the United States, he built some extra time into his schedule, rented a car, and drove to Mechanicsburg to look for Rhein. The man he had contacted previously was at first furious that the young Dutchman had come there without setting anything up in advance, but when he met Martjan face to face, he liked him and decided to help him set up a meeting with Rhein.

Martjan had no idea what to expect of the film when he met Rhein the following morning. Perhaps it would be a blurry mess. He just hoped that the bird in the film was identifiable as an Imperial Woodpecker. As the old 16mm projector rolled noisily and the film flickered on the portable screen in Rhein’s living room, a huge woodpecker suddenly appeared, its forward-curved black crest bouncing jauntily as it hitched up a massive pine trunk. Martjan was stunned. There was no doubt about it—this was an adult female Imperial Woodpecker. The bird foraged, chipping off chunks of bark, and then flew away, but the show didn’t end there. Rhein had filmed several other short segments of the bird as she flew, foraged, and hitched up trees—sometimes in real time, other times in slow motion. This single 85-second clip held a gold mine of information about a barely studied species.

Why hadn’t Rhein told the scientific world about his Imperial Woodpecker footage? Perhaps he was embarrassed by the quality of it, which had been filmed with a hand-held movie camera from the back of a mule. Other films and still photographs he had taken always had a far more professional quality to them. Rhein said he would have a copy of the film made for Martjan, but he did not receive it until after Rhein had passed away a couple of years later.

When Martjan came to Cornell to be lead scientist of the Lab of Ornithology’s Ivory-billed Woodpecker project, he brought a DVD of the Imperial Woodpecker footage with him and played it for a group of us one afternoon. It gave me chills to see the bird—such a remarkable species, and so beautiful. Watching Rhein’s film is what ultimately inspired me to launch my own search. Here was footage of this near-mythical bird—tangible evidence of its existence taken during my lifetime—and it somehow made the quest seem more real. I soon started making forays into the high country of the Sierra Madre Occidental.

It was a different world there, almost like stepping back in time to the 19th century. The people—many of whom are Tarahumara, Tepehuan, or other indigenous groups—live mostly in adobe huts and cabins without electricity, plumbing, telephones, or other modern conveniences. They rely primarily on horses and mules to get around, which is not such a bad way to go. The mountain roads are atrocious for any kind of motor vehicle, and in many places it takes hours just to drive 30 or 40 miles.

But that’s not the worst of it. The Sierra Madre has become a major drug-growing region where illicit crops of opium poppies and marijuana thrive. So in the same places where indigenous people engage in their traditional pursuits you also encounter heavily armed drug traffickers driving gleaming new four-wheel-drive trucks with dark-tinted windows. The situation has deteriorated steadily for several years. Government forces are currently locked in a deadly struggle with drug cartels, and the level of violence has reached horrendous levels in some areas, with massacres, assassinations, and kidnappings becoming increasingly common. And now it is spreading into some of the most remote sections of the mountains.

I made several journeys into the northern section of the Sierra Madre in the state of Chihuahua, traveling through the rim forests along the Barranca del Cobre (Copper Canyon) and in the high country above the villages of Garcia, Pacheco, and Chuhuichupa, where many Imperial Woodpecker specimens were collected a century or more earlier. I had some unsettling encounters with drug growers as well as heavily armed government troops (some with their faces masked by balaclavas to protect their identities) at remote roadblocks.

Still, I was eager to get together with Martjan and explore the area surrounding Rhein’s film site. This would be my first foray into the state of Durango. We had been talking about it for months, and the expedition seemed more and more imperative as we studied satellite maps of the area. Using Google Earth and clues in several of Rhein’s letters, Martjan had tried to decipher exactly where the footage of the woodpecker had been taken, and while doing so, he noticed several areas of uncut forest nearby on high mesas with steep rocky sides.

Although Martjan is as pessimistic as anyone about the chances that Imperial Woodpeckers might still exist, he had found people with seemingly credible sightings of the species in the 1990s, and I interviewed some men in 2009 who had seen birds within the past five years that matched the description of an Imperial Woodpecker, so it seemed possible that a handful of them might yet linger on. As we sat looking at those Google Earth images on a computer, we became increasingly excited about going there. What if these places were like tiny relics of a pristine ecosystem where Imperial Woodpeckers might still survive?

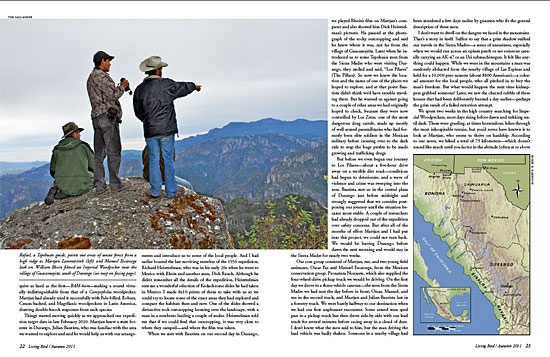

Martjan had developed a new way to look for Campephilus woodpeckers (the genus that includes Ivory-billed and Imperial woodpeckers as well as nine other Latin American species), and we were eager to try it out in the mountains of Mexico. He had created a device to mimic the characteristic double-knock drum of most Campephilus woodpeckers, hoping that if an Imperial Woodpecker were in the vicinity when he made the sound, it might respond with a double knock of its own. The typical double knock is lightning fast and sounds like BAM-bam, the second bam fainter, almost like an echo of the first. The device Martjan designed has two parts—one looks like a wooden birdhouse and is strapped tightly to a tree trunk to act as a resonator, amplifying the sound and giving it a natural wooden quality; the other consists of two broomstick-sized pieces of dowel, each nearly a yard long, connected to each other with a pivot bolt. You swing the dowel assembly overhand in an arc, striking the box with one of the dowels, and the other dowel swings over and down from the pivot point, hitting the box a fraction of a second later and not quite as hard as the first—BAM-bam—making a sound virtually indistinguishable from that of a Campephilus woodpecker. Martjan had already tried it successfully with Pale-billed, Robust, Cream-backed, and Magellanic woodpeckers in Latin America, drawing double-knock responses from each species.

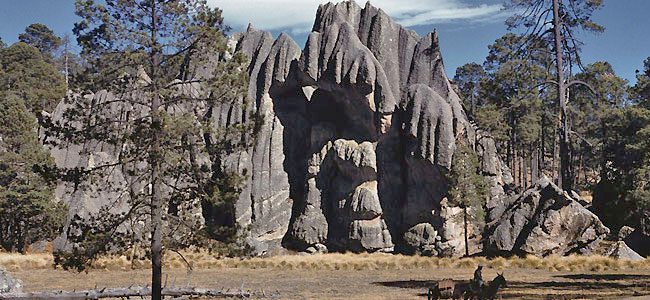

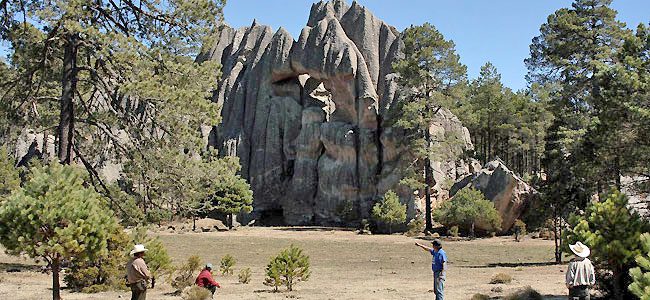

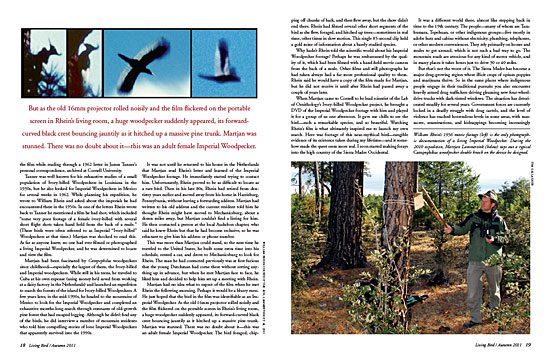

Things started moving quickly as we approached our expedition target date in late February 2010. Martjan knew a state forester in Durango, Julian Bautista, who was familiar with the area we wanted to explore and said he would help us with our arrangements and introduce us to some of the local people. And I had earlier located the last surviving member of the 1956 expedition, Richard Heintzelman, who was in his early 20s when he went to Mexico with Rhein and another man, Dick Rauch. Although he didn’t remember all the details of the expedition, Heintzelman sent me a wonderful selection of Kodachrome slides he had taken in Mexico. I made 8×10 prints of them to take with us so we could try to locate some of the exact areas they had explored and compare the habitats then and now. One of the slides showed a distinctive rock outcropping looming over the landscape, with a man in a sombrero leading a couple of mules. Heintzelman told me that if we could find that outcropping, it was very close to where they camped—and where the film was taken.

The left photo shows the open understory and large pines in 1956. In the right, the same area is pictured in 2010. Photo by Martjan Lammertink.

On the right, Rhein crosses a bunchgrass clearing among old-growth pines in 1956. Photo by R.C. Heintzelman.

Using a 1956 photo to find the spot where the Imperial Woodpecker was filmed on Rhein's trip. Photo by Martjan Lammertink.

The Los Pilares rock formation in 1956 with vegetation at the base of the rocks. Photo by R.C. Heintzelman.

Los Pilares in 2010. The bunchgrass has disappeared from overgrazing. Photo by Martjan Lammertink.

The view from the mountaintops. Photo by Tim Gallagher.

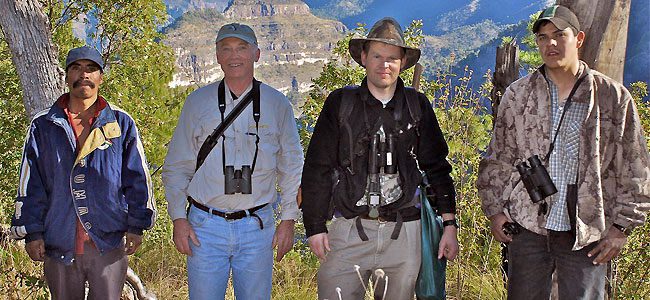

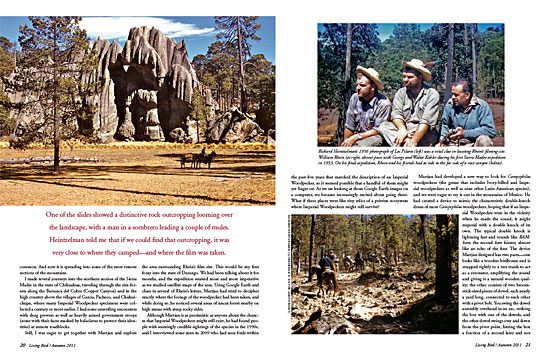

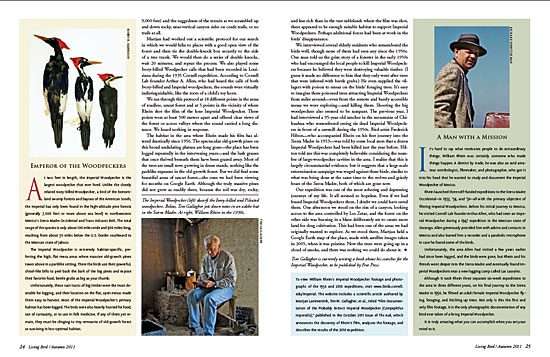

From left to right: Antonio Peña, Tim Gallagher, Martjan Lammertink, and Manuel Escarcega. Photo by Oscar Paz.

Martjan Lammertink creates the typical Campephilus double-knock sound to see what turns up. Photo by Tim Gallagher.

Martjan Lammertink creates the typical Campephilus double-knock sound to see what turns up. Photo by Tim Gallagher.

Felix Morales de la Cruz says he last saw Imperial Woodpeckers in the mid-fifties. Photo by Martjan Lammertink.

Nicolasa Gonzalez, on the far left, also saw imperials in the fifties, but none since. Photo by Martjan Lammertink.

When we met with Bautista on our second day in Durango, we played Rhein’s film on Martjan’s computer and also showed him Dick Heintzelman’s pictures. He paused at the photograph of the rocky outcropping and said he knew where it was, not far from the village of Guacamayita. Later when he introduced us to some Tepehuan men from the Sierra Madre who were visiting Durango, they smiled and said, “Los Pilares” (The Pillars). So now we knew the location and the name of one of the places we hoped to explore, and at that point Bautista didn’t think we’d have trouble traveling there. But he warned us against going to a couple of other areas we had originally hoped to check, because they were now controlled by Los Zetas, one of the most dangerous drug cartels, made up mostly of well-armed paramilitaries who had formerly been elite soldiers in the Mexican military before crossing over to the dark side to reap the huge profits to be made growing and trafficking drugs.

But before we even began our journey to Los Pilares—about a five-hour drive away on a terrible dirt road—conditions had begun to deteriorate, and a wave of violence and crime was sweeping into the area. Bautista met us in the central plaza of Durango just before midnight and strongly suggested that we consider postponing our journey until the situation became more stable. A couple of researchers had already dropped out of the expedition over safety concerns. But after all of the months of effort Martjan and I had put into this project, we could not turn back. We would be leaving Durango before dawn the next morning and would stay in the Sierra Madre for nearly two weeks.

Our core group consisted of Martjan, me, and two young field assistants, Oscar Paz and Manuel Escarcega, from the Mexican conservation group, Pronatura Noroeste, which also supplied the four-wheel-drive pickup truck we would be driving. On the first day we drove in a three-vehicle caravan—the men from the Sierra Madre we had met the day before in front; Oscar, Manuel, and me in the second truck; and Martjan and Julian Bautista last in a forestry truck. We were barely halfway to our destination when we had our first unpleasant encounter. Some armed men sped past in a pickup truck but then drove side-by-side with our lead truck for several minutes before racing away in a cloud of dust. I don’t know what the men said to him, but the man driving the lead vehicle was badly shaken. Someone in a nearby village had been murdered a few days earlier by gunmen who fit the general description of these men.

I don’t want to dwell on the dangers we faced in the mountains. That’s a story in itself. Suffice to say that a grim shadow stalked our travels in the Sierra Madre—a sense of uneasiness, especially when we would run across an opium patch or see someone casually carrying an AK-47 or an Uzi submachinegun. It felt like anything could happen. While we were in the mountains a man was randomly abducted from the nearby village of Las Espinas and held for a 10,000 peso ransom (about $800 American)—a colossal amount for the local people, who all pitched in to buy the man’s freedom. But what would happen the next time kidnappers grabbed someone? Later, we saw the charred rubble of three houses that had been deliberately burned a day earlier—perhaps the grim result of a failed extortion attempt.

We spent two weeks in the high country searching for Imperial Woodpeckers, most days rising before dawn and trekking until dark. These were grueling, at times horrendous, hikes through the most inhospitable terrain, but you’d never have known it to look at Martjan, who seems to thrive on hardship. According to our notes, we hiked a total of 73 kilometers—which doesn’t sound like much until you factor in the altitude (often at or above 9,000 feet) and the ruggedness of the terrain as we scrambled up and down rocky, near-vertical canyon sides on crude trails, or no trails at all.

Martjan had worked out a scientific protocol for our search in which we would hike to places with a good open view of the forest and then tie the double-knock box securely to the side of a tree trunk. We would then do a series of double knocks, wait 20 minutes, and repeat the process. We also played some Ivory-billed Woodpecker calls that had been recorded in Louisiana during the 1935 Cornell expedition. According to Cornell Lab founder Arthur A. Allen, who had heard the calls of both Ivory-billed and Imperial woodpeckers, the sounds were virtually indistinguishable, like the toots of a child’s toy horn.

We ran through this protocol at 18 different points in the areas of roadless, uncut forest and at 5 points in the vicinity of where Rhein shot the film of the lone Imperial Woodpecker. These points were at least 500 meters apart and offered clear views of the forest or across valleys where the sound carried a long distance. We heard nothing in response.

The habitat in the area where Rhein made his film has altered drastically since 1956. The spectacular old-growth pines on this broad undulating plateau are long gone—the place has been logged repeatedly in the intervening years—and the lush grasses that once thrived beneath them have been grazed away. Most of the trees are small now, growing in dense stands, nothing like the parklike expanses in the old-growth forest. But we did find some beautiful areas of uncut forest—the ones we had been viewing for months on Google Earth. Although the truly massive pines did not grow as readily there, because the soil was dry, rocky, and less rich than in the vast tablelands where the film was shot, there appeared to be enough suitable habitat to support Imperial Woodpeckers. Perhaps additional forces had been at work in the birds’ disappearance.

We interviewed several elderly residents who remembered the birds well, though none of them had seen any since the 1950s. One man told us the grim story of a forester in the early 1950s who had encouraged the local people to kill Imperial Woodpeckers because he believed they were destroying valuable timber. (I guess it made no difference to him that they only went after trees that were infested with beetle grubs.) He even supplied the villagers with poison to smear on the birds’ foraging trees. It’s easy to imagine these poisoned trees attracting Imperial Woodpeckers from miles around—even from the remote and barely accessible mesas we were exploring—and killing them. Shooting the big woodpeckers also seemed to be rampant. The previous year, I had interviewed a 95-year-old rancher in the mountains of Chihuahua who remembered seeing six dead Imperial Woodpeckers in front of a sawmill during the 1950s. Bird artist Frederick Hilton—who accompanied Rhein on his first journey into the Sierra Madre in 1953—was told by some local men that a dozen Imperial Woodpeckers had been killed just the year before. Hilton told me this was completely believable considering the number of large-woodpecker cavities in the area. I realize that this is largely circumstantial evidence, but it suggests that a large-scale extermination campaign was waged against these birds, similar to what was being done at the same time to the wolves and grizzly bears of the Sierra Madre, both of which are gone now.

Our expedition was one of the most sobering and depressing journeys of my life. It all seemed so hopeless. Even if we had found Imperial Woodpeckers there, I doubt we could have saved them. One afternoon we stood on the rim of a canyon, looking across to the area controlled by Los Zetas, and the forest on the other side was burning in a blaze deliberately set to create more land for drug cultivation. This had been one of the areas we had originally wanted to explore. As we stood there, Martjan held a Google Earth map of the place, made with satellite images taken in 2005, when it was pristine. Now the trees were going up in a cloud of smoke, and there was nothing we could do about it.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library