Flooding Fields in the Mississippi Delta Helps Crop Yields—and Shorebirds

By Vanessa Gregory

A flock of Least Sandpipers. Photo by Larry Pace. June 25, 2021Near the birthplace of B.B. King, scientists and farmers are working together to temporarily flood fields, create migratory shorebird habitat, and even grow more soybeans.

From the Summer 2021 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

One bright October morning, James Failing sat on his truck’s tailgate and watched hundreds of shorebirds—Stilt Sandpipers, Long-billed Dowitchers, Roseate Spoonbills—flitting amid the broken cornstalks that rose above flooded fields. Like his grandfather and father before him, Mr. Failing has dedicated his life to farming in the fertile Mississippi Delta.

But fall 2020 marked only his third year of creating temporary habitat for bird migration.

“If you put a little water out, it’s amazing,” Failing said. “You have all sorts of birds, and I don’t know where they come from or how they know, but they really come bombing in incredibly quickly.”

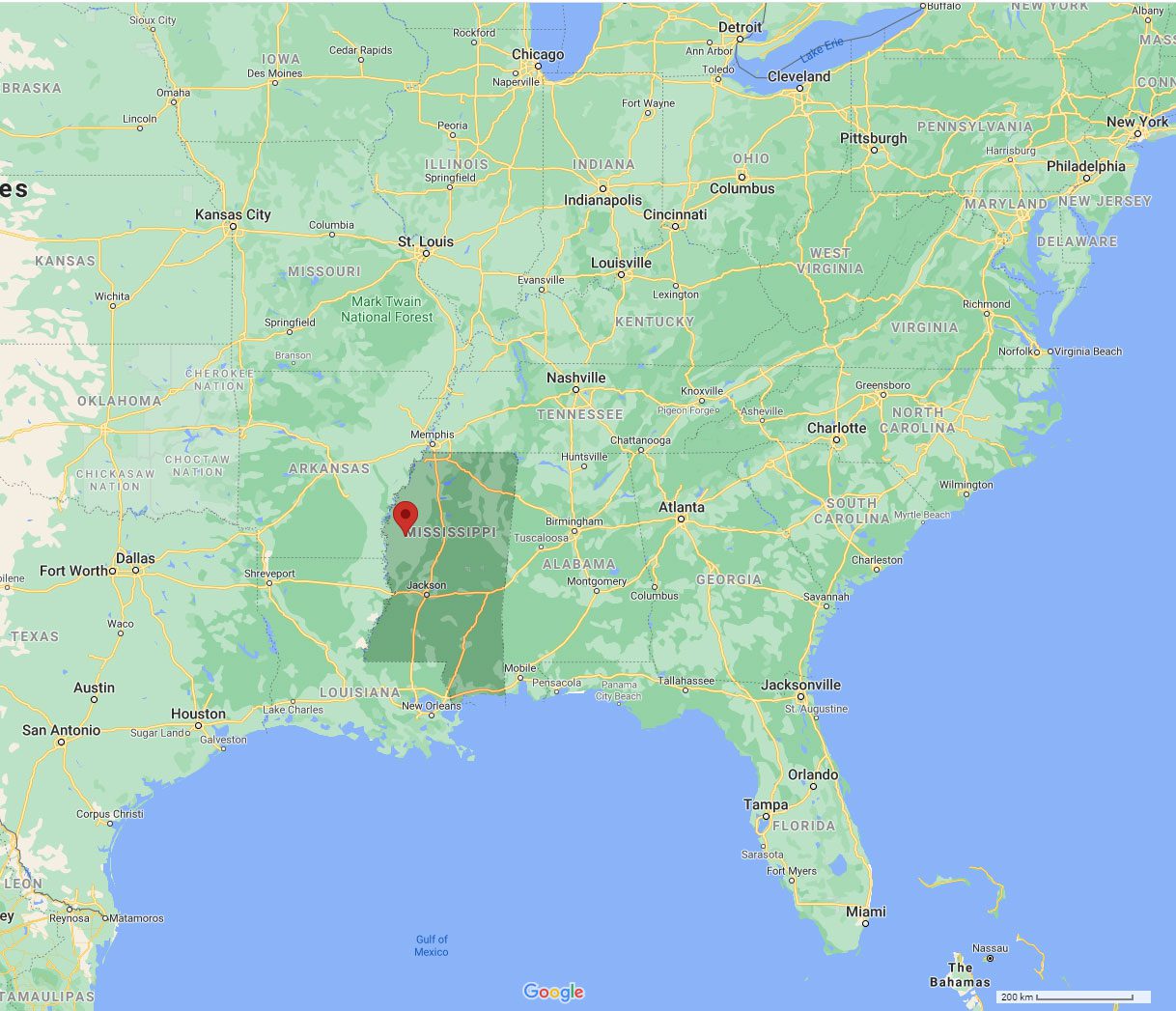

The shorebirds came from as far as thousands of miles away, some on migration from the Arctic. By the time they reached Failing’s fields near Indianola, Mississippi, wetland habitat was scarce. Agriculture dominates the Delta, a region more famous for bluesmen like the late B.B. King than for innovative conservation projects. But Failing’s corn and soybean farm was an exception; it doubled as a field site for researchers exploring how early-fall flooding might help not only birds, but also farmers and the broader ecosystem.

“Most conservation organizations, their interest is in benefiting wildlife, and they don’t necessarily have the resources to do all this ancillary research,” said Jason Hoeksema, an ecologist and evolutionary biologist at the University of Mississippi and a cofounder of Delta Wind Birds, the nonprofit that paid Failing to flood his fields in early September. Hoeksema, who has a tattoo of a Hudsonian Godwit on his left forearm, wasn’t initially thinking beyond birds either. He just needed an open-minded farmer with the infrastructure to capture and recycle water runoff, so Delta Wind Birds could make wetland habitat without depleting already fragile aquifers.

A casual conversation with his neighbor Jason Taylor, an aquatic ecologist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s research service, broadened Hoeksema’s outlook. Taylor mentioned that unused nitrogen—from the fertilizers used for growing crops—leaches off farm fields after harvest, entering waterways and contributing to algal blooms and oxygen-starved dead zones, like the big one in the Gulf of Mexico.

Temporary wetlands, Taylor said, could minimize nitrogen leaching by facilitating denitrification, a microbial process that transforms the polluting form of nitrogen into harmless nitrogen gas (the stuff that makes up 78% of our atmosphere).

“[Denitrification] happens in wetlands naturally, and in a lot of aquatic environments,” Taylor said. “The idea is, by flooding, we’re returning this essential wetlands function to the fields.”

Ecologist Jason Hoeksema monitors the flooded fields on James Failing’s farm. Migratory shorebirds flocked to this temporary wetland habitat. Photo by Larry Pace.

Hoesksema and the nonprofit group Delta Wind Birds found that nitrogen runoff was reduced by 30% to 40%, and the soybean yield increased. Photo by Larry Pace.

Taylor partnered with Hoeksema and found that the temporary wetlands on Failing’s farm removed 30% to 40% of excess nitrogen that otherwise would have run off into the ecosystem. Soil erosion was also significantly reduced on the flooded acreage, which is a big benefit to farmers.

Plus, the wet plots teemed with biomass: around 4,000 organisms, primarily midge larvae, per square meter. That’s a boon to birds seeking fuel for migration, but those invertebrates also shuffle carbon around, which Taylor hypothesized could support healthy microbial communities and improve soil fertility.

Read More

One piece of early evidence supports that idea: Failing’s crop yield data showed that flooded land produced about four extra bushels of soybeans per acre. A seemingly small boost, but it can be huge for farmers living on small profit margins.

“The first 75 bushels of beans, you’re no money, no money, no money,” Failing said. “Those marginal bushels? That’s all we’re really living for.”

Hoeksema and Taylor plan to replicate and expand their research on at least three more farms in the Mississippi Delta, with the support of a $1 million grant from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Their work might one day persuade more Delta farmers to adopt seasonal flooding for birds. The Mississippi Delta, along with parts of Arkansas and Louisiana, sits at the intersection of critical bird-migration flyways, and the region holds at least 200 farms with environmentally friendly water systems for temporarily flooding fields.

“If you could flood 100 acres on each of those farms, you’d have 20,000 acres of temporary wetlands,” Hoeksema said. “That’s more than enough habitat for all the birds that migrate through every fall.”

One hitch might be agricultural chemicals. Researchers hope to track how residues of weed killers applied in farm fields might enter the food chain and affect birds. It will take a few years to figure out, Taylor said, but most herbicides break down fairly quickly. The bigger barrier may be finding other farmers like Failing, who now keeps a foldout field guide to waterbirds on the dashboard of his pickup truck and can identify American Avocets through his binoculars.

Brad Andres, the national coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Shorebird Conservation Partnership, said that Taylor and Hoeksema’s work fits within a working-lands approach that’s gaining momentum in bird conservation.

“I think that’s kind of the way we’re headed in parts of the bird conservation community, of trying to really figure out what the human well-being benefits are for shorebird habitats,” Andres said. “They’re not just for the birds, but for birds and people.”

Vanessa Gregory lives in Oxford, Mississippi, where she teaches journalism at the University of Mississippi. Her work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, Harper’s Magazine, and Orion Magazine.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library