California’s Tricolored Blackbird Is Running Out of Room

By Ben Goldfarb

Tricolored Blackbird by Nigel Voaden/Macaulay Library. March 31, 2019From the Spring 2019 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

Every spring for millennia, California has hosted one of America’s grandest wild spectacles: the gathering of the Tricolored Blackbird. Agelaius tricolor breeds in colonies that historically numbered in the hundreds of thousands. On the wing, wrote one observer in 1853, they “darken the sky for some distance by their masses.” A tricolor supercolony gathered in a cattail marsh is a deafening riot of screaming males and nest-weaving females, a cacophonous congregation that protects itself from predators with sheer abundance. Although they are most closely related to the Red-winged Blackbird, the tricolor’s truest soulmate is another gregarious species whose flocks once blotted out the sun: the Passenger Pigeon.

The similarities between Tricolored Blackbirds and Passenger Pigeons do not, unfortunately, end with their behavior. California’s Central Valley is today the world’s most productive farmland, but it was once puddled by 4 million acres of wetlands—and teeming with tricolors. In the 1930s, biologist Johnson Neff conducted surveys for the federal government and found colonies so dense that one small willow could support a dozen nests. Neff estimated the total population at more than 1.5 million birds—including one colony near Sacramento that supported nearly a half-million blackbirds in 1932. The majesty didn’t last.

“By 1935,” Neff wrote, “(gold) dredgers had so changed the terrain that only 2,000 to 3,000 birds returned to this place.”

Neff’s account was a typical one. A century of ditching, diking, and draining sucked dry more than 90 percent of the Central Valley’s wetlands, with severe consequences for tricolors. Today just 175,000 or so of these blackbirds remain—fewer than once amassed in a single colony.

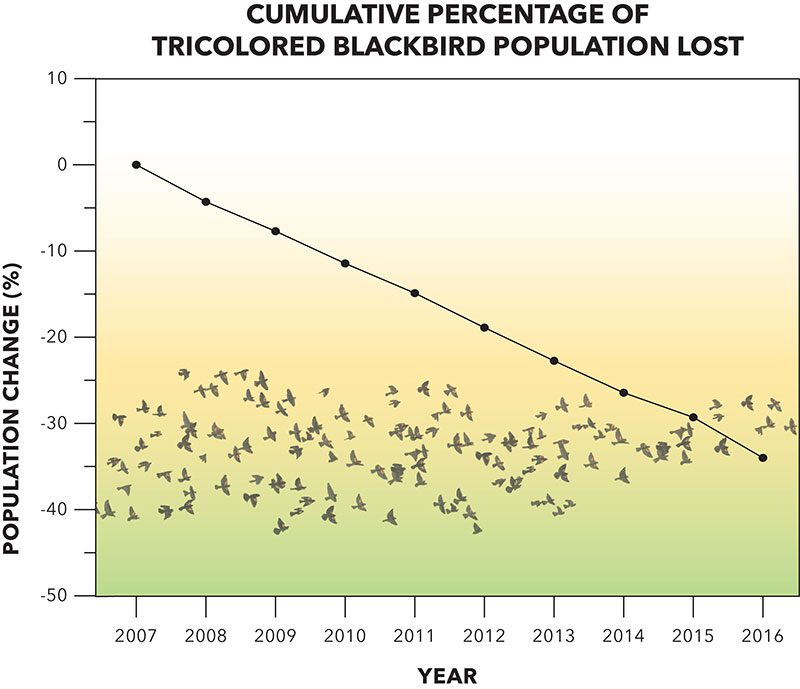

Tricolors still form the largest colonies of any living North American songbird, but their freefall has only gotten steeper. As recently as 2006, one grouping numbered nearly 140,000. Just a decade later, in 2017, the largest colony was down to 17,500 blackbirds.

While the destruction of California’s wetlands was the original sin, Tricolored Blackbirds today face a daunting array of threats. With their natural habitat depleted, the birds have attempted to eke out a living in agricultural fields, with limited success. Their foraging grounds have been converted to almond orchards, their insect prey dosed with pesticides, their nests literally plowed under. They are imperiled, in a sense, by modernity itself, by the pressure inherent to squeezing the world’s fifth-largest economy into a single state. They are a species that gathers in great numbers, struggling to survive on a landscape with little room for wildlife.

“The decline has been rapid, it has been dramatic, and it is ongoing,” says University of California–Davis biologist Bob Meese. “You have to wonder, what does the future hold?”

Can These Fighters Evade Defeat?

One December afternoon, Meese and I visit a farm near the Sacramento Delta to see how tricolors are faring in the 21st century. The farm, nestled between lush hills, is bucolic: Sheep loll along a shallow creek; wind turbines twirl atop ridgelines. Meese parks on balding grass, among modern agriculture’s beasts of burden: balers, loaders, tractors, combines. It’s an unlikely refuge for a large overwintering flock of a vanishing bird, but in the Californian Anthropocene, this is the best of what’s left.

Although Tricolored Blackbirds range from northern Mexico to southeastern Washington throughout the year, around 99 percent dwell in the Golden State, primarily overwintering on dairy ranches, rice farms, and wildlife refuges in Central California and along the coast. Observing them in December, when they’re not aggregated on their breeding grounds in spectacular numbers, is a bit like fishing a salmon stream before the spawn—nice enough, but a bit beside the point. Still, it’s a fine site for birding. A mixed flock of Red-winged Blackbirds, Brewer’s Blackbirds, European Starlings, and Brown-headed Cowbirds shifts restlessly over the fields, picking at spilled grain. With a bit of coaching from Meese, I quickly learn to separate the Tricolored Blackbirds from the redwings: They sport red-and-white shoulder epaulets rather than red-and-yellow, and a slightly longer and narrower bill.

Red-winged and Tricolored Blackbirds can be differentiated by their epaulets. Tricolor males have a white stripe beneath the bright red shoulder patch. Photo by John Puschock/Macaulay Library.

A male Red-winged Blackbird shows off the yellowish stripe below his red shoulder patch. Photo by Don Danko/Macaulay Library.

Soon I’m seeing tricolors, or “trikes,” everywhere—atop fenceposts, arrayed along power lines, even alighting on obliging sheep. Every few minutes the birds lift in a whoosh of wings, rising and falling in hypnotic murmurations. During one such flight, a Peregrine Falcon, its steely back glinting, glides through the flock in a half-hearted attack, parting the startled blackbirds like Moses striding through the Red Sea.

Although Meese appreciates the pastoral beauty, what he notices most is what’s missing. A raptor biologist by training, Meese began studying Tricolored Blackbirds in 2005 at the behest of Bill Hamilton, UC Davis’s aging blackbird don, who sought an heir to his own decades-long monitoring project. Using homemade wood-framed traps baited with cracked corn, Meese has since captured, banded, and released some 90,000 tricolors—more than any biologist alive. Many of Meese’s captures have been on this very farm. One afternoon in 2007, he counted 50,000 Tricolored Blackbirds here, hardly a starling or redwing among them. The hillsides that day were obsidian with trikes; in one photograph, the birds fill every edge of the frame.

These days, the flock numbers 4,000, and tricolors are in the minority.

“It’s impossible to take a picture like that anymore,” laments Meese. “I’d be shocked if they came back.”

To understand this precipitous decline, it helps to know something about Tricolored Blackbirds. They’re finicky about where they live, insistent on three key ingredients at any breeding site. First, they need a water source—a bird has to drink and bathe, after all. Second, they demand dense, predator-proof nesting vegetation, like cattails or bulrushes. Finally, they need food sources for their ravenous chicks.

“The most important thing is a reliable source of large-bodied insects…grasshoppers, dragonflies, damselflies, says Ted Beedy, a UC Davis biology alum who has studied tricolors since the 1980s. “Without that, the colony will almost invariably fail.”

Once a colony finds an acceptable patch, males stake out territories just a few meters square and announce their ownership with ear-splitting, almost feline shrieks. To a mottled female blackbird, the ungodly screech is as sweet as a Shakespearean sonnet. With the near-perfect synchrony of a square dance, females choose partners, copulate, knit cuplike nests, and lay eggs. The din erupts again when the chicks hatch, as columns of adult birds beeline from their nests to retrieve insect prey for their offspring.

Once the chicks have fledged, incredibly, their parents engage in a behavior known as itinerant breeding, flying north—typically dozens of miles up the Central Valley, sometimes as far as southeastern Oregon—to repeat the laborious ritual at a new site.

Today, though, finding even one suitable breeding location is a challenge. With their marshes drained, Tricolored Blackbirds often settle for patches of invasive weeds, like Himalayan blackberry. They also rely on grainfields. Trikes are especially fond of a crop called triticale, a wheat-rye hybrid that dairy farmers grow as silage to feed their cows. One 2013 study found that blackbird colonies in triticale were 40 times larger than those in other nesting plants.

“They’re fighters,” says Samantha Arthur, conservation project director at Audubon California. “They’re good at utilizing this altered landscape.”

The shelter of grainfields, however, often proves illusory. By sad coincidence, the best time to harvest triticale overlaps precisely with Tricolored Blackbird nesting season. When heavy machinery faces off against newborn chicks, the inevitable result is tragedy. In 1994, for instance, farmers wiped out two colonies totaling more than 60,000 birds. In 1999, a 14,000-bird colony was mowed down. In 2003, a colony of 80,000 birds fell victim. At a Merced County farm in 2006, Bob Meese witnessed the carnage firsthand, as a combine plowed through thousands of nests while swarms of frenzied adults flushed and screamed. Meese posted a video of the massacre on YouTube.

“I wouldn’t be doing my job if I didn’t document the reality on the ground,” he says.

Conservationists have tried to avert such tragedies. In the 1990s, state and federal agencies began paying farmers to delay their harvests until chicks fledged. The payments compensated farmers for the dwindling nutritional value of silage left in the field longer. Meese calculates that from 2005 to 2009 such payments saved 396,000 fledglings. But the reimbursements were ad hoc and underfunded, and colonies continued to be razed. Dairy farmers weren’t pleased with the ambiguity, either.

“Every year we were wondering, is there going to be funding? And where’s it coming from?” recalls Paul Sousa, director of environmental services for Western United Dairymen.

Both sides finally received some certainty in 2015, in the form of a $1.1 million grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The five-year grant, administered to Audubon California and Western United Dairymen, created a protocol for reporting colonies in grainfields, and guaranteed farmers compensation for postponing harvests. In 2017 the program protected five sites totaling nearly 75,000 birds. In 2018 it saved all known tricolor colonies. Sousa says it also changed the attitudes of farmers, many of whom had considered tricolors a costly pest.

“There’s often some concern when [farmers] find out there are birds nesting in their fields, but the compensation helps them come to ease with it,” he says.

Rice farms, too, have benefited from blackbird conservation. Later in the week, Meese and I stop by the Conaway Ranch, a 17,000-acre farm with a checkerboard of rice paddies shimmering with standing water. Many California rice farmers flood their fields each winter to break down old plant stubble left behind after the harvest. In the process, they create a simulacrum of the rich wetlands that once soaked the state. On this morning, rafts of Tundra Swans float on the paddies, and Great Blue Herons stalk the irrigation ditches. Meese points out Tricolored Blackbirds among the passerine flocks flitting over the scene. He estimates he’s banded nearly 20,000 tricolors here.

“It’s almost like my second home,” he says.

Conaway Ranch’s robust tricolor population is largely a credit to operations manager Mike Hall, an affable man whose office is adorned with photos of his hunting and fishing exploits. Although Hall is tasked with managing the ranch to promote waterfowl, no species occupies more of his attention than tricolors. By carefully burning the ranch’s stands of cattails each winter, Hall maintains the early-stage vegetation that affords the best nesting habitat. Conaway Ranch also maintains organic, pesticide-free rice fields, which nourish insect prey for blackbirds. In 2012, California’s Wildlife Conservation Board purchased a half-million-dollar easement on this ranch, ensuring that 224 acres will forever remain devoted to tricolors.

“It’s good PR for the ranch, too,” Hall admits with a laugh.

Yet the Conaway Ranch model may not be a replicable one.

“We have so many acres that we have that flexibility,” Hall says. “Not too many farmers can say, okay, we’re going to dedicate over 200 acres to this one species.”

Rice easements and dairy compensation programs might be enough to slow the Tricolored Blackbird’s decline, but saving California’s signature songbird will require even greater change.

How Citizen Science is Helping a Bird Pushed to the Limits

Much of what we know about Tricolored Blackbirds we owe to citizen scientists.

Tricolor colonies are transient by nature, vanishing and reappearing from year to year. As another cattail marsh gets drained here, the birds move to an enticing tangle of Himalayan blackberry there.

In 1994, Ted Beedy decided that quantifying the Tricolored Blackbird population would require an organized volunteer survey of the state. He recruited around 30 birders to canvass the California countryside for trikes. Beedy’s brainchild has since exploded into a massive undertaking. Over the last two and a half decades, on one spring weekend every three years, around 100 citizen scientists cruise the state’s dusty back roads, scanning fields for telltale processions of blackbirds streaming across the horizon. The herculean effort, now overseen by Meese, has produced major discoveries. In April 2017, Debi Shearwater (the pelagic birding superstar) ventured inland and stumbled upon five previously unknown tricolor colonies in San Benito and Monterey Counties, more than 13,000 birds in total. One of the colonies faced imminent mowing, but the birds were spared thanks to Shearwater’s intervention and the landowner compensation program.

“I have seen a mowed colony, with dead birds everywhere, and I cannot bear to see that again,” Shearwater says with a shudder. “I would have gone out there and stood in the field in front of the mower if I had to.”

For every new colony that surveyors find, however, two more seem to vanish. In 1994, Beedy’s initial survey counted around 370,000 birds. By 2017, the count had fallen to 177,000, only about 10 percent of historic populations.

Yet legal protection continued to elude tricolors, even as the species tanked. When the Center for Biological Diversity petitioned the state of California and the federal government to protect the birds with a threatened or endangered listing in 2004, the request was dismissed for lack of scientific evidence. In 2014, the group tried again with another petition to list tricolors under the California state Endangered Species Act.

The intervening decade between petitions saw the advent of supercomputing, and this time the state of California had to account for the research of Orin Robinson, a postdoctoral researcher at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology who specializes in big-data population modeling. In a study published last year in the journal Biological Conservation, Robinson combined more than 100,000 birding checklists filed to eBird (the Cornell Lab’s citizen-science database) with land-cover data he had cross-referenced from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to identify which habitats the birds were using most. He then combined that information with Bob Meese’s years of banding and recapture data to create a robust, statistically sound portrait of a species in dire trouble. Robinson estimated that tricolors had declined by 34 percent since 2007, and he found that the crash was primarily due to losses during the breeding season.

“This shows that you’ll get the most bang for your buck through conservation actions that improve reproductive success,” Robinson says—a nod toward strategies like protecting nesting colonies in agricultural fields, when the birds are imperiled by harvesters’ blades.

In April 2018 the California Fish and Game Commission convened to reconsider the Tricolored Blackbird’s status. This time the voting was unanimous: By a 4-0 tally, the commissioners declared tricolors threatened under the California ESA.

“There was no doubt in our minds that the population had been declining,” says Neil Clipperton, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife biologist who wrote the status review recommending the birds for listing. “It was reassuring to see that corroboration from another data source, and extremely useful to know that lack of reproductive success had been driving that trend.”

For tricolors, the decision arrived in the nick of time. The listing imposes tough penalties on landowners who mow down nesting colonies. That’s especially significant given the Trump administration’s 2017 decision to relax the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, a reinterpretation that could have permitted such “incidental” killing.

“The state stepped up and provided protection to these birds right when the federal government was pulling back,” says Audubon California’s Arthur.

Not even state listing, however, can protect tricolors from the invisible hand of the food industry. Driven by the world’s insatiable appetite for almonds and pistachios, California’s farmers have gone crazy for nut orchards, which require neatly groomed grounds that make for poor Tricolored Blackbird habitat. To drive through the Central Valley today is to witness extreme agricultural upheaval. Lines of pistachio seedlings poke from plastic sheaths, an eerie army on the march. Walnut trees reach skyward with skeletal arms. And everywhere, there are sprawling rows of stout almond trees—more than a half-million new almond acres since 1997.

Among the many threats tricolors face, the nut takeover scares conservationists most. Though Tricolored Blackbirds are admirable survivors with adaptable diets (they feast on spilled grain, snatch insects from midair, even flip over cowpies to gobble larvae), the biologically sterile nut orchards are a step too far. The second-largest tricolor colony in California nests on a dairy farm with an owner who plans to convert his pastures into pistachios.

“If he does that, it’s lights out,” Meese says.

In fairness, it’s hard to blame farmers for trying to stay profitable. California’s dairy farmers are suffering from years of sinking milk prices, while rice growers are bedeviled by hikes in water rates resulting from the state’s ongoing drought. As farming profits continue to get squeezed, converting fields to pistachios and almonds looks appealing.

Paul Buttner, manager of environmental affairs at the California Rice Commission, warns that such conversions come at a steep price for birds.

“There’s nothing that’s going to replace those winter-flooded [rice] acres from a wetland perspective,” he says.

Will History Repeat itself?

Our world is growing inhospitable to jaw-dropping wildlife abundance. Bison herds that evoke rolling thunder, shorebird flocks that blanket mudflats, herring so bountiful that rivers run silver—not quite gone, but woefully diminished. In the 21st century, strength no longer lies in numbers. Instead, abundance is a liability.

Consider, for a moment, the Sixth Extinction’s most famous victim: the Passenger Pigeon. Ectopistes migratorius was blasted out of the sky by hunters, yet the final blow was likely dealt by the bird’s own biology. Like Tricolored Blackbirds, Passenger Pigeons were exquisitely adapted for their gregarious lifestyle; their mating behavior, foraging tactics, and predator defenses evolved within the context of vast flocks. Hunters didn’t need to shoot all of them to wipe them out. They just needed to kill enough to disrupt their social behavior, to reduce flocks below the threshold at which their evolutionary strategies became maladaptive. Their very plenitude was, in the end, their downfall.

Might history now be repeating itself?

“The adaptation to nest in large, social colonies is what’s so special about Tricolored Blackbirds,” says Audubon California’s Arthur. “And yet it’s also what makes them vulnerable.”

Take predation. Tricolored Blackbird colonies have always attracted predators, including coyotes, raccoons, and raptors. When tricolors bred in the uncountable thousands, they could endure the losses. Now that many aggregations hover in the mere hundreds, the abundance strategy is becoming obsolete. These days, even Cattle Egrets can destroy colonies.

An even greater crisis may lie with the Tricolored Blackbird’s prey. While adult tricolors can subsist on a surprising variety of foods, their chicks need protein-rich insects. A single breeding colony of 2,000 blackbirds can consume a million grasshoppers in a season. But once-reliable bugs are getting scarcer. In 2016 alone, California’s farmers applied more than 430,000 pounds of neonicotinoids, the same class of insecticides that have been implicated in the demise of honeybees and other insects. When Meese and colleagues compared pesticide application to Tricolored Blackbird population trends, they found a strong correlation. As farmers used more pounds of neonicotinoids along California’s Central Coast and in the San Joaquin Valley, tricolor numbers dwindled. In areas where the pesticide was employed less intensively, the bird remained comparatively stable.

With agricultural fields increasingly destitute, blackbirds are depending more and more on public land—in particular, the Sacramento National Wildlife Refuge Complex, a constellation of eight wetlands that supports nearly 300 bird species. In winter, the Pacific Flyway’s waterfowl descend, and flotillas of Snow Geese turn the refuges’ basins white as cotton fields. Tricolored Blackbirds are less conspicuous than geese, but no less important. In recent years, refuge staff began irrigating some areas to produce aquatic insects for hungry tricolors.

“We’ve seen birds using these newly flooded areas,” says refuge wildlife biologist Mike Carpenter.

While tricolor habitat is contracting everywhere else, it’s expanding on these federal refuges. In 2009, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service acquired 308 acres of rice paddies adjacent to the Colusa National Wildlife Refuge and converted them to a cattail wetland. A survey counted 16,000 Tricolored Blackbirds breeding in the new wetland in 2017. If you build it, they will come.

Yet the refuges are tiny islands of public acreage in an ocean of private farmland. The goal for biological recovery set by the Tricolored Blackbird Working Group—a collaboration of government agencies and farming and environmental groups—is a sustained population of 500,000 to 750,000, which seems like an impossible dream.

“There is no room in California for 500,000 Tricolored Blackbirds,” Meese laments back on the sheep farm, as we watch blackbirds splash energetically in the shallow creek. “Period. It doesn’t exist.”

The sun has now begun to set behind the hills, and the sheep-dotted fields have turned a lambent orange. As if by mutual agreement, a few dozen birds lift into the sky, spiraling like a column of campfire smoke. Another cluster takes off, and another, winging west into the setting sun toward their roost in the Sacramento Delta. Soon an avian mass is aloft—redwings, cowbirds, starlings, and, interspersed, a few precious tricolors—the cloud of birds a single superorganism climbing toward the ridge.

We’ve lost so much; and yet there’s much left to save.

“Hope you make it through the night,” Meese calls to the birds, and they’re gone.

Ben Goldfarb is an environmental journalist whose work has appeared in Orion, Audubon, and The Guardian. He is also the author of the book Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library