Slideshow: If You’ve Seen These Birds, Thank the Endangered Species Act

September 5, 2018

The national emblem of the United States might have gone extinct without the Endangered Species Act. In the 1960s, Bald Eagles hit a low of just over 400 pairs in the Lower 48. Today, a quarter-million of the magnificent birds soar over North America. Bald Eagle by Brian Kushner via Birdshare.

Goofy, graceful, and gregarious, Brown Pelicans are beloved sights along many U.S. beaches as long lines of the big birds cruise on broad wings just inches above the water. This species nearly vanished in the 1970s but recovered so strongly that it was delisted in 2009. Brown Pelican by Salah Baazizi via Birdshare.

Often described as the fastest animal in the world, Peregrine Falcons nearly vanished from the eastern United States because of DDT pollution. Thanks to intense conservation efforts and captive breeding, this magnificent raptor was delisted in 1999. Peregrine Falcon by Pete Blanchard via Birdshare.

Like other large birds, Wood Storks were vulnerable to the effects of the pesticide DDT, which weakened their eggshells. And as wetland specialists, they were affected by changing water use and draining of wetlands. They were listed in 1984, and the U.S. population has more than doubled since then. Wood Stork by B.N. Singh via Birdshare.

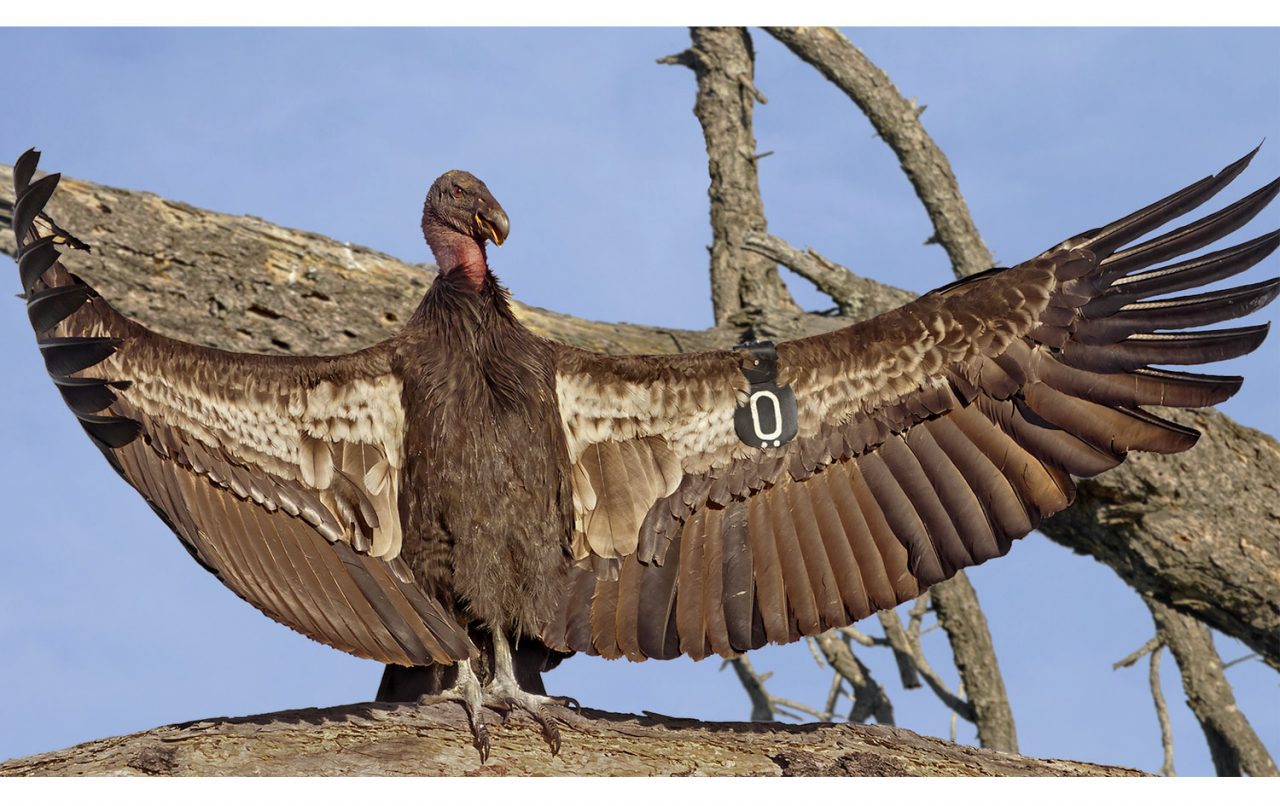

Simultaneously a success story and an ongoing project, the California Condor was brought back from the brink of extinction—just 22 birds in the early 1980s—to more than 250 free-flying individuals today. Yet continuing problems, particularly poisoning from lead ammunition, mean the condor still requires major effort and investment to survive. Learn more in our story. California Condor by CT_Imagery via Birdshare.

Aplomado Falcons range across grasslands from the Mexico to South America, but they disappeared from the extreme southern U.S. by the 1950s. An intensive captive breeding and reintroduction program led by the Peregrine Fund brought them back, and the species now flies in South Texas and the Southwest again. Aplomado Falcon by Christian Fernandez /Macaulay Library.

One of the most recognizable and beloved of all endangered species, the Whooping Crane is an ongoing recovery project involving captive breeding and innovative projects to reintroduce the birds and teach them their migratory routes. The species now numbers about 400 in the wild. Whooping Crane by Tom Blandford via Birdshare.

The Piping Plover is vulnerable to beach and nesting-area development and disturbance. It was listed in 1985 and since then conservation efforts have helped their numbers to increase more than threefold. Piping Plover by B.N. Singh via Birdshare.

A casualty of intense logging of the majestic longleaf pines of the southeastern U.S., the Red-cockaded Woodpecker hangs on in scattered longleaf preserves and frequently burned loblolly and slash pine stands. The ESA has allowed scientists to learn an incredible amount about this small, colonially breeding woodpecker with a meticulous approach to creating its nest holes—leading to a 42% increase in their numbers. Red-cockaded Woodpecker by Craig Brelsford/Macaulay Library.

A species emblematic of the controversy over the protection of natural resources, the Northern Spotted Owl continues to survive in the last of the great old-growth forests of the Pacific Northwest, although it's being further threatened by newly arrived Barred Owls. Read the full story. Image by Ben Phalan/Macaulay Library.

Thanks to intensive management and protection from cowbirds, Kirtland's Warbler numbers have climbed tenfold since the species was listed in the 1970s, and it was proposed for delisting earlier this year. Learn more in our story. Kirtland's Warbler by Jason Jablonski via Birdshare.

The Black-capped Vireo once numbered fewer than 1,000 individuals. It was listed in 1987 and by 2018 had recovered to some 14,000 individuals—enough for the species to be delisted. Black-capped Vireo by Bradley Hacker/Macaulay Library.

The striking Golden-cheeked Warbler breeds only in a small region of Texas, where habitat restoration and efforts to reduce cowbird parasitism have helped the population rebound. Golden-cheeked Warbler by Jesse Huth/Macaulay Library.

The state bird of Hawaii is this small, beautiful goose. Once restricted to a few high elevation sites, the Hawaiian Goose or Nene now occurs on multiple islands and is one of the few native Hawaiian species with an increasing population. Image by SharifUddin59 via Birdshare.

The Florida Scrub-Jay hangs on in scattered pockets of sandhills in the midst of intense development in Central Florida. Sadly, its numbers continue to fall, even with ESA protection—which may be at least slowing their decline. Florida Scrub-Jay by Cleber Ferreira via Birdshare.

Sadly, not all species survived long enough to come under the protection of the ESA. Two examples are the Passenger Pigeon (left) and Carolina Parakeet (right). These paintings by John James Audubon are stark reminders of how much is at stake when we weigh the costs and benefits of conservation.

Birds are all around us—even birds that were once on the brink of extinction. Bald Eagles now occur in every mainland state in the U.S. Peregrine Falcons scream over barren coastlines and hunt Rock Pigeons in cities. Brown Pelicans delight beachgoers with their low-slung glides and crashing dives. And the list goes on.

Many of these recoveries are thanks to the hard work and commitment represented by the Endangered Species Act and the people who dedicate their careers to helping species. To celebrate, we’ve put together this slideshow showing just some of the birds the Act has helped turn around. You can see a comprehensive list in a report published by the American Bird Conservancy: it finds 70% of all listed bird species are better off today.

When you see any of these species, take a moment and thank the Endangered Species Act.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library