When 136 Bird Species Show Up at a Feeder, Which One Wins?

By Alison Haigh

January 8, 2018

From the Winter 2018 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

There’s something tranquil about watching birds coexist at your backyard feeder, pecking away in their quirky abandon. That is, until the local Blue Jay arrives, flushing all your daintier songbirds out in a raucous flurry. It might seem like just plain bullying, but there’s more going on than meets the eye in the fast-moving (and frankly addicting) world of bird-feeder drama. Setting out a limited food resource (like a feeder full of seeds) in a time of scarcity (like winter) naturally brings birds into conflict. Just beyond your kitchen windowpane, your backyard feeder is creating the perfect stage to glimpse the inner workings of birds’ social lives—what behavioral ecologists call “dominance hierarchies.”

Birds at feeders are like members of a not-so-secret fight club, and the rulebook is in the dominance hierarchy. For a chance to eat in the safety of a flock, they must constantly appease, avoid, or consequently get walloped by more dominant birds. Scientists have spent decades working out the dominance hierarchies among just two or three species. But now, with the help of thousands of citizen scientists, a team of researchers has pieced together a hierarchy that ranks the feeder-fight-club performance of 136 North American bird species.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology postdoctoral associate Eliot Miller spearheaded the analysis and now holds the results. Miller found his volunteers through Project FeederWatch, a joint Cornell Lab and Bird Studies Canada project that recruits more than 20,000 backyard bird watchers from coast to coast. Miller asked feeder watchers who were already counting birds to record any “interspecific interactions” (or interactions among species) that could define the hierarchy. For example, if a White-breasted Nuthatch flared its wings at a Black-capped Chickadee, and the chickadee flew off from the feeder in response, that classified as a “successful displacement.” Feeder watchers recorded 7,653 such observations between November 2016 and April 2017.

Using a computer program, Miller collapsed that data set into “ability scores” for each species: a single number that describes each species’ ability to compete with others. It ranged from an alpha bird (the Wild Turkey at 66.93) to the meekest of the bunch (Eurasian Tree Sparrow at –24.46). In the same way college basketball teams can be ranked even though they don’t all play each other, this metric allowed scientists to generate scores for comparing birds that don’t normally interact. From there, constructing the dominance hierarchy was easy: “We just ranked species based on their scores,” said Miller.

The full 136-species data set is too big to fit in a single graph, but explore this diagram to see how North America’s top 13 feeder species fared:

When comparing where a bird fell on the dominance hierarchy to where it fell on a weight scale, a general rule emerged: the bigger the bird, the badder. If you were the size of a White-throated Sparrow (score: –1.86), you’d shy away from a Common Raven (38.19), too.

But as with most general rules in the natural world, there are exceptions. Doves were more subordinate and had lower scores than their burly stature would imply, thus living up to their peaceful reputation. Woodpeckers, warblers, and hummingbirds all performed better than expected, placing them surprisingly high on the dominance hierarchy. In other words, they punched above their weight.

“Warblers are just pugnacious little things,” Miller said, referring to the Yellow-rumped, Pine, Palm, Townsend’s, and Orange-crowned Warblers in his feeder study. “They’re hopped up on testosterone a lot of times and are used to defending winter territories, while most other feeder birds aren’t.”

He also noted that “hummingbirds defend floral resources against other hummingbirds constantly, and very aggressively. It makes them good fighters.”

Heavy bills and strong claws make woodpeckers the plucky under-birds of their weight class. Eastern Bluebirds (score: –0.84) are outranked by the smaller Downy Woodpecker (score: –0.64), which perhaps isn’t surprising given that woodpeckers are built for smashing their heads into tree trunks.

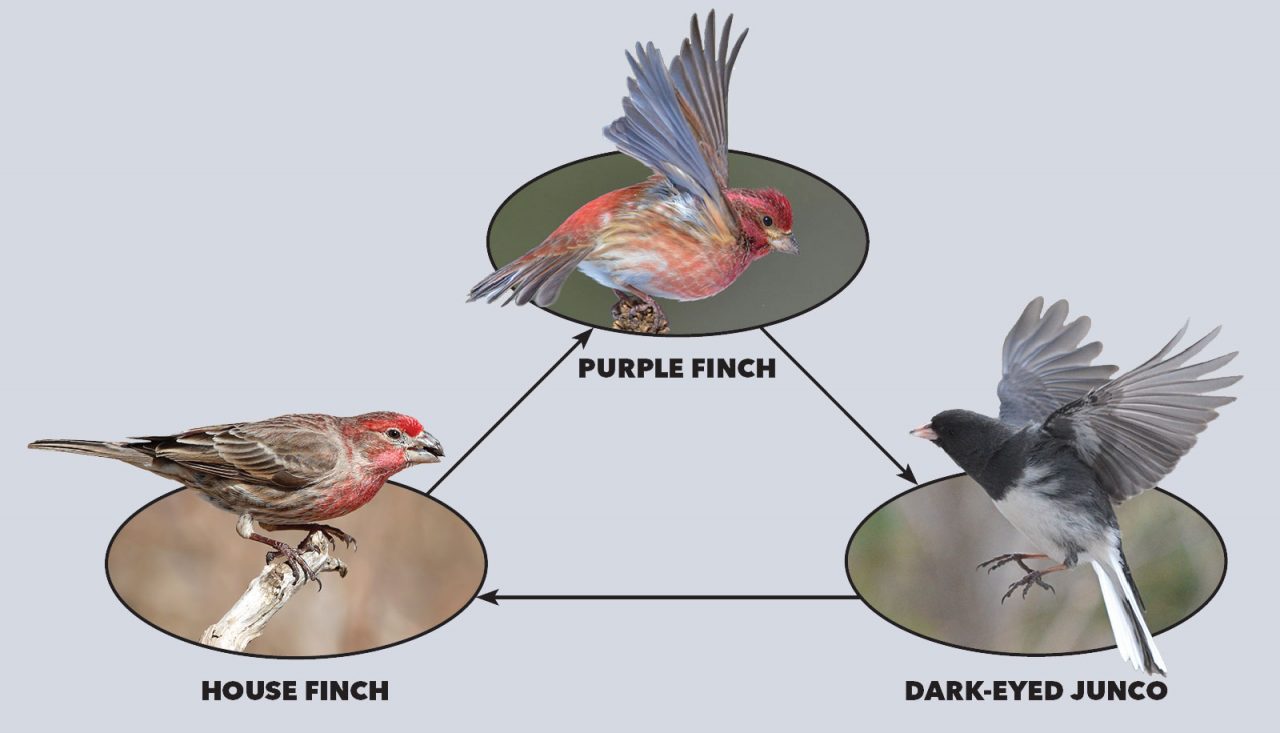

Not every dominance pattern is linear, though. A separate analysis uncovered some dominance triangles in which three birds had one-to-one relationships independent of each other, like a game of birdy rock-paper-scissors. For example, the House Finch dominates the Purple Finch, and the Purple Finch dominates the Dark-eyed Junco, but the junco dominates House Finch.

Red-headed Woodpeckers, Red-bellied Woodpeckers, and European Starlings, which all compete for nesting cavities, are locked in a similar dominance triangle. In that case, Miller notes that starlings are an invasive species that “might be disrupting a nicely constructed hierarchy.”

Miller says he has only scratched the surface of studying dominance hierarchies. These hierarchies could vary seasonally, or between habitats or regions. For example, Lesser Goldfinches are dominant to Pine Siskins in Texas, but the opposite is true in Oregon.

Miller also thinks dominance may play a role in defining a bird’s range.

“Interactions with competitors might shape [species] distributions,” he explains. For example, he wonders if Red-breasted Nuthatches are capable of breeding farther south in higher numbers, but they just can’t compete with the White-breasted Nuthatches that already live there. The Red-breasted Nuthatch’s ability score of –3.50 is nearly a full point less than the White-breasted Nuthatch’s, at –2.51.

“We really know very little about how potential competitors interact where their ranges overlap,” says Miller. In fact, he admits that his original research question was supposed to be about the effect of dominance on where birds establish territories, but studying dominance itself pulled him in. “I’ve been a bit sidetracked now, in a good way, exploring the dominance hierarchy itself.”

He has a right to be. As the first to talk about an interspecific hierarchy with this many members, Miller is breaking the rules a bit. After all, the first rule of bird-feeder fight club is, don’t squawk about it.

Alison Haigh is an Environmental Biology and Applied Ecology major at Cornell University (class of 2019). Her work on this story was made possible by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology Science Communication Fund, with support from Jay Branegan (Cornell ’72) and Stefania Pittaluga.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library