The Farm Bill Protects Birds and Clean Water. Here’s How

By Gustave Axelson

September 18, 2017

From the Autumn 2017 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

The Farm Bill is typically associated with corn and soybeans, but it does a pretty good job of growing ducks, too.

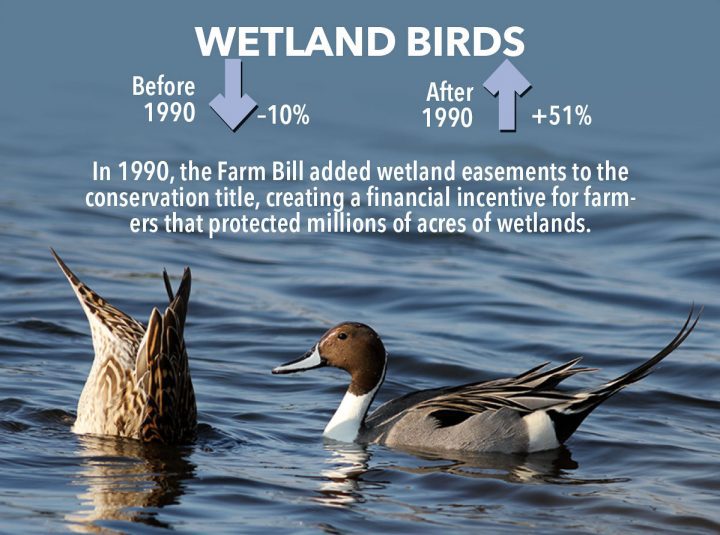

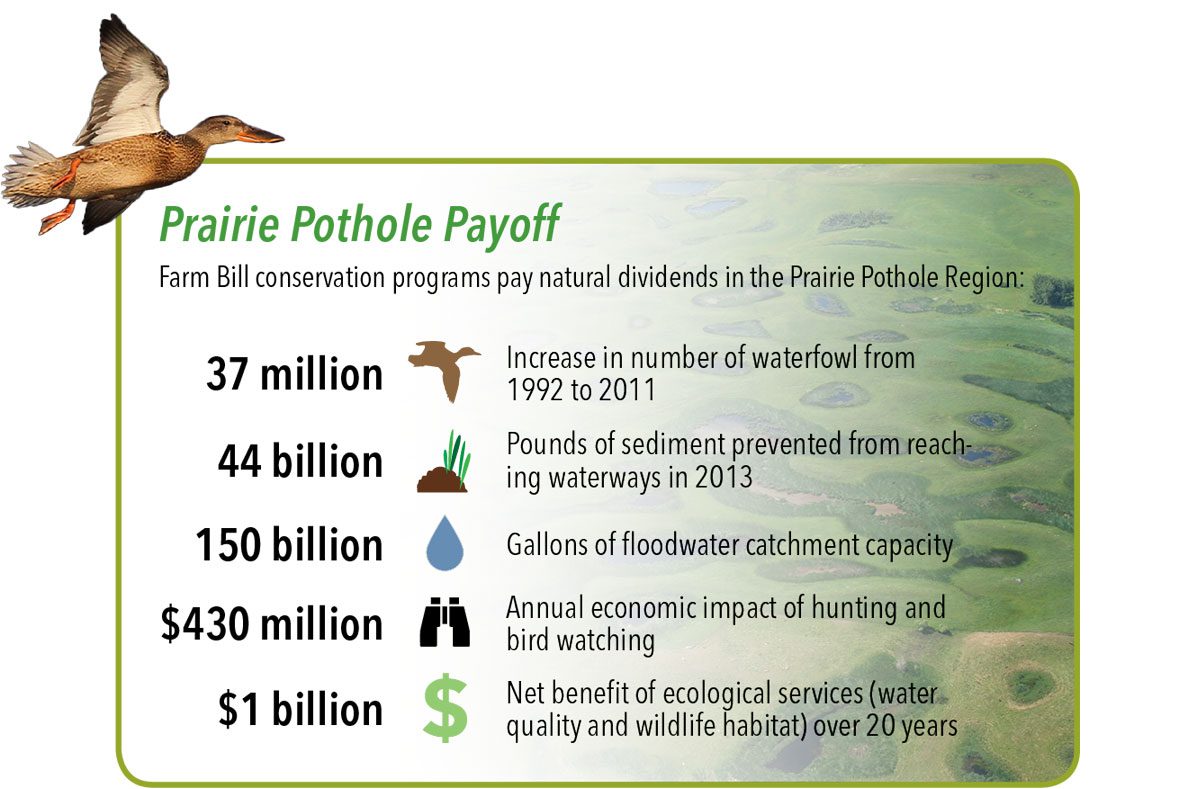

Between 1992 and 2011, Farm Bill conservation programs enacted habitat improvements on private farmland in the Prairie Pothole Region that boosted waterfowl production by 37 million ducks, according to the 2017 State of the Birds report.

The report—published in August by the North American Bird Conservation Initiative, a coalition of 28 government agencies and nonprofit groups including the Cornell Lab of Ornithology—spotlights the vital role that the Farm Bill plays in conserving bird habitat.

While most of the Farm Bill dictates federal agriculture policy, the Farm Bill’s conservation and forestry titles also allocate billions of dollars in federal conservation program funding on private lands. In the Lower 48 States, private lands constitute more than 60 percent of the land area, including 911 million acres of farmland and another 400 million acres of private forests. According to the State of the Birds report, more than 100 bird species in the U.S. rely on habitat on private lands.

Farm Bill conservation programs provide financial incentives for farmers, ranchers, and forest owners to adopt ecosystem-friendly practices, such as easements that pay landowners to maintain grasslands and wetlands on their property. While some critics knock such programs as “paying farmers not to farm,” the reality is that Farm Bill conservation programs compensate landowners for ecological services—such as clean water—that flow from a farm to benefit the entire community. For example, grasslands in Illinois created by the Farm Bill and other programs provided $900 million in flood control, groundwater recharge, and water purification services to the Chicagoland area, according to the report.

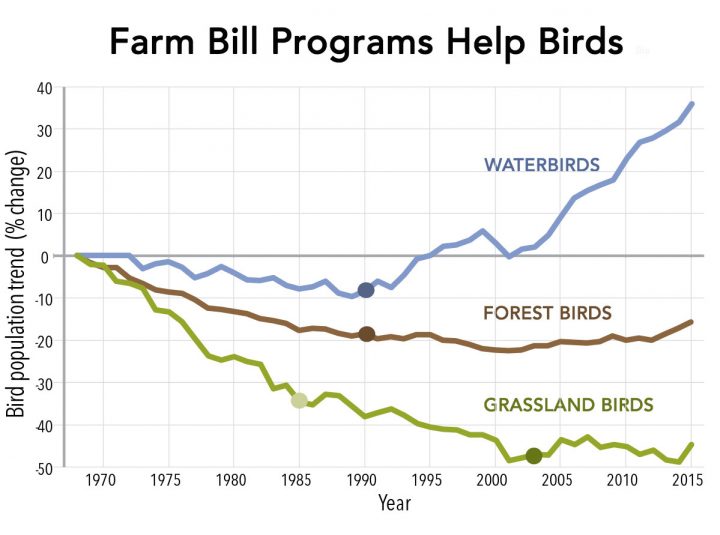

Each time the Farm Bill has introduced a conservation program (dots), bird populations have leveled out or rebounded. See following slides for more details about each group.

Northern Pintails by Kevin McGowan.

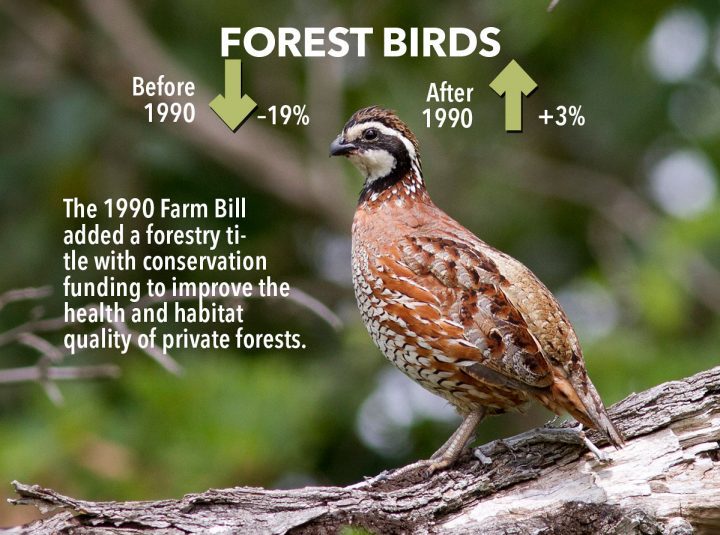

Northern Bobwhite by Linda Chittum/Macaulay Library.

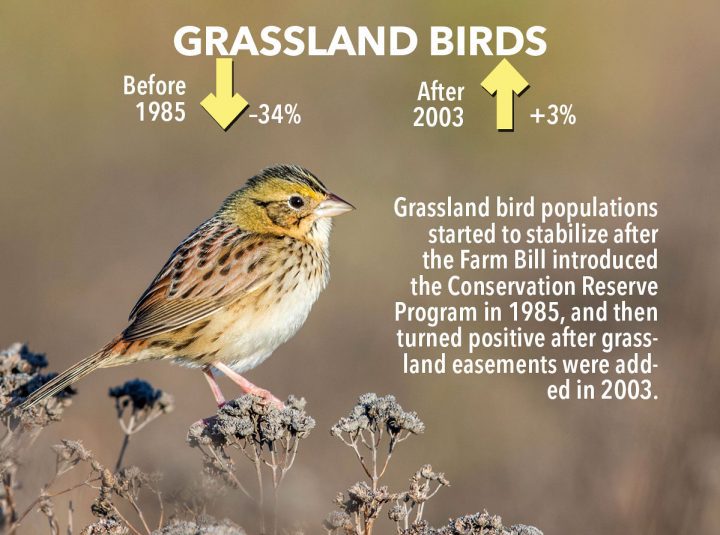

Henslow’s Sparrow by Jeff Timmons/Macaulay Library.

The report also shows how birds respond to the Farm Bill. Population trends for wetland, forest, and grassland birds all showed positive turnarounds following the introduction of key Farm Bill conservation programs.

“The Farm Bill’s conservation provisions have helped to stabilize populations of grassland birds, which had suffered a nearly 50 percent drop before grassland easements were introduced in 2003,” said Ken Rosenberg, an author of the report and conservation scientist at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. “Since that time, we’ve seen an encouraging 3 percent increase in numbers.”

In 2018 the Farm Bill is due for an update and revision by Congress, and conservationists are hopeful regardless of the outcome last time, when the 2014 Farm Bill reduced conservation funding by $4 billion.

“Despite cuts in the last Farm Bill, conservation did have policy victories,” says Kellis Moss, director of public policy for Ducks Unlimited. As one of the big wins, Moss points to rules that made farmers ineligible for federal crop insurance subsidies if they drained wetlands or plowed up native grasslands. The 2014 Farm Bill also strengthened regional conservation partnerships, such as the Sage Grouse Initiative in the West, and put a greater emphasis on purchasing habitat easements on private lands.

“Farm Bill conservation program demand far exceeds current funding,” says Moss, pointing out that many farmers who apply for conservation programs are turned away because the programs run out of money. “We hope to see greater funding for these programs that benefit producers, taxpayers, and wildlife.”

The next Farm Bill will be written during a time of economic stress in rural America. Farmers and ranchers have experienced a 45 percent drop in net farm income since 2014, the largest three-year drop since the Great Depression. Since 2012, per-bushel corn prices have dropped by half, and bankruptcy filings among small farms in Iowa were up 125 percent in 2016. That means farmers and ranchers may welcome the financial compensation provided by enrolling some of their land in the Farm Bill’s Conservation Reserve Program, or CRP.

“CRP is another tool in the toolbox for landowners to use when they are trying to diversify their holdings,” said Nathan Franzen of the American Bankers Association at a House Commodity Exchanges subcommittee hearing. “CRP can provide a steady stream of income for producers.”

Farm income isn’t the only thing declining in farm country. Grasslands continue to be plowed up. In 2007 there were more than 36 million acres of CRP grasslands on private farms in the U.S., but after Farm Bill conservation funding cuts there are about 25 million CRP acres today. The rate of grassland loss in the western Corn Belt from 2006 to 2011 was comparable to tropical deforestation rates in Brazil and Indonesia. Wetlands also continue to be drained. Despite a stated no-net-loss wetlands federal policy, the Prairie Pothole Region lost more than 125,000 acres of emergent wetlands to conversion to agriculture between 1997 and 2009.

“The no-net-loss of wetland policy goal has not yet been reached in the [Prairie Pothole] region,” admitted the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in a report published in 2014.

Not coincidentally, the “dead zone” in the Gulf of Mexico—an oxygen-depleted area where fish can’t survive—has grown to almost 8,800 square miles, an area the size of New Jersey. It’s the biggest Gulf dead zone ever measured by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. And it’s fed by water runoff from cropfields, as scientist Don Scavia told National Public Radio in August.

Read the Report

“Most of the nitrogen and phosphorus that drives this problem comes from the Upper Midwest,” said Scavia, who initiated NOAA’s dead zone survey more than 30 years ago. “It’s coming from agriculture.”

So in the name of clean water, and birds, and even stable farm income, there’s a lot riding on the Conservation Title of the next Farm Bill. So far, Congress has signaled that it plans to defend conservation in the Farm Bill.

“The [Trump] administration’s proposal for major cuts to the Farm Bill conservation programs has thus far not been supported by Congress,” said Steve Holmer, vice president of policy at the American Bird Conservancy. “The 2018 Farm Bill will hopefully build on its previous successes by fully supporting conservation programs.”

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library