Jack Pine Juggernauts: What Will Happen to Kirtland’s Warblers After Delisting?

By Greg Breining; Photos by Craig Watson

June 8, 2017From the Summer 2017 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

Amid a sea of scrubby jack pine, several scientists gather as a male Kirtland’s Warbler—one of several within earshot—sits on the tip of a tree branch and fills the sky with his buoyant, clear song. The large warbler, with dandelion-yellow breast and slate-blue head and back, stands out as clearly as a traffic sign. It seems somehow incongruent that one of the continent’s rarest migratory birds would sing so boldly in plain view, only 30 feet away.

“Oh, we can get way closer,” marvels Nathan Cooper, a researcher at the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center. “They just sing. They seem to sing all the time.”

The spirited male makes no effort to hide or evade. “They just don’t know any better,” adds Peter Marra, the head of the Smithsonian center and an expert in songbird migration and population dynamics.

The task of finding a singing Kirtland’s Warbler on its nesting ground would have been vastly harder three decades ago. At that time, the entire known population numbered only 167 breeding pairs scattered across the jack pine barrens of the northern portion of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula. But in the years since, the boisterous warbler has multiplied to more than 2,000 pairs and has spread—albeit tentatively—to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, northern Wisconsin, and across the border to Ontario.

“I think it’s a tremendous success story,” says Marra. “Are we out of hot water? No, I would say we’re not out of hot water, especially given some of the threats that we’re seeing during the nonbreeding season, like climate change and sea level rise,” which could affect the warbler’s wintering habitat in the low-lying Caribbean.

“So it’s important that we continue to do this kind of research to really understand as much as we can about the species and to get the population size as high as we possibly can so it’s safe, not just for the next 50 years but maybe 200, 300 years.”

The success and upward trajectory of the warbler’s numbers has prompted the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to consider downlisting the Kirtland’s from “endangered” to “threatened” on the federal endangered species list, or removing it altogether.

But hurdles remain. And even if the path is cleared for removing endangered species protections entirely, the Kirtland’s Warbler will remain utterly dependent on continued human maintenance of its breeding habitat.

“The Kirtland’s Warbler is one of those ‘conservation-reliant’ species,” says Christie Deloria, a Fish and Wildlife Service biologist and member of the Kirtland’s recovery team who has worked with the species for more than 20 years.

“This is a species that’s going to need our attention into the future,” she says. “There are many other listed species that are in the same boat. But what’s unique maybe with Kirtland’s is that we’ve had huge success at recovering the species. And we are perhaps one of the first groups to be figuring out how do we take a conservation-reliant species off of the endangered species list.”

Habitat Loss and Cowbird Eggs

The Kirtland’s is jumbo by warbler standards—up to 15 grams, about twice the size of an American Redstart. It was named for an Ohio doctor and naturalist (Jared Potter Kirtland), but sometimes it is called the “jack pine warbler,” because it habitually nests on the ground beneath young jack pines. And it is there that the long story of its decline and near-extinction begins.

Each spring Kirtland’s Warblers fly north from the Bahamas to Michigan, where they pair up and nest almost exclusively in large tracts of jack pine between 1 to 4 meters (3 to 12 feet) tall. Marra says it’s not clear why Kirtland’s Warblers will nest only among young trees. But it is clear that once the stand reaches about 15 years old, the birds disappear.

It’s also not clear if the warbler’s reliance on young jack pine evolved since the last glacial retreat about 10,000 years ago, or if the bird has followed jack pine forests at glacial margins through several ice ages. But the warbler and jack pine are inextricably linked now, and the only natural way to create sweeping stands of scraggly young jack pine is through forest fire.

In the past, fires were ignited by lightning and also by indigenous peoples to create openings for game and forest crops, such as blueberries. The Kirtland’s was probably never common, even in its Michigan range. Its numbers may have peaked in the late 1800s, when wildfires scorched the land in the wake of pine logging. By the 1920s, settlers got serious about stomping out wildfire. The amount of land in warbler territory that burned each year fell from an average of 14,000 acres (based on fire records) to only about 1,000. Jack pine grew too old and tall to interest warblers.

Vanishing habitat wasn’t the only problem. By the early 1900s, Brown-headed Cowbirds were becoming common, taking advantage of the openings created by logging and agriculture. Cowbirds lay their eggs in the nests of other birds, and the cowbird young hatch early and monopolize food. The first instance of cowbird parasitism of a Kirtland’s Warbler’s nest was reported in 1908. The warbler seemed unable to identify the intruders or remove their eggs or even defend its own young. Parasitism rates ranged from 48 to 86 percent of Kirtland’s Warbler nests, according to Fish and Wildlife researchers William Shake and James Mattsson. Kirtland’s nests on average produced fewer than a single warbler fledgling.

As fire-generated habitat disappeared and cowbirds invaded, the number of warblers plummeted. A 1951 census counted only 432 singing males in 28 townships. By 1971, the number had fallen to 201 in just 16 townships. In 1974 and again in 1987, the population hit its nadir at 167 singing males.

A High-Maintenance Project Pays Off

As early as 1957, state and federal wildlife managers began creating more jack pine stands to benefit warblers. In 1973, the Kirtland’s Warbler became one of the first species protected under the Endangered Species Act. A recovery team of federal and state biologists aimed to “reestablish a self-sustaining Kirtland’s Warbler population throughout its known range at a minimum level of 1,000 pairs.”

More On Birds Coming Back From the Brink

Foresters created habitat through clearcutting and then prescribed burning. But the thousands of homes, cabins, and trailers tucked into the woods along dirt roads and country highways made fire a risky bet. The Mack Lake fire in 1980 forced a major rethinking in strategy.

On the morning of May 5, a district ranger on the Huron National Forest gave the okay to light a prescribed burn in southern Oscoda County. As described in a 1981 article in American Forests magazine, relative humidity was low and the temperature, already 74, was forecast to rise during the day. Several spot fires broke out along the perimeter of the burn. Shortly after noon, fire leapt into the crowns of jack pine along Highway 33. By 12:20 p.m. the call went out that the Forest Service needed help. The fire was out of control.

Seven hours later, according to American Forests, nearly 25,000 acres were charred. Forty-four homes and cabins were damaged or destroyed. A Forest Service fire technician was dead. Local resident Joe Walker remarked as he raked through the remains of his cabin, “I hope that warbler enjoys his nest. My nest is burned.”

Mack Lake made the use of fire fraught, if not impossible. Instead, land managers developed a method of clearcutting and mechanical planting, incorporating half-acre openings among the rows of jack pine. Currently, about 4,000 acres are harvested and replanted each year, about half on state land and half on the Huron-Manistee and Hiawatha National Forests. The timber management is purely in the name of habitat—young jack pines have very little commercial value.

Creating habitat was one thing, but keeping cowbirds away was another. In 1972, the Fish and Wildlife Service began trapping cowbirds and quickly reduced parasitism to less than 10 percent of Kirtland’s Warbler nests. The rate has continued to drop as the agency has spent roughly $100,000 a year to capture and euthanize an average of nearly 4,000 cowbirds each season in Michigan.

That two-pronged approach did the trick. By the late 1980s, Kirtland’s Warblers began to increase in number. Annual production of young has more than tripled to 3.52 young fledged per nest attempt. The species surpassed its recovery goal of 1,000 breeding pairs in 2001 and has doubled since then.

Despite this success, the Kirtland’s Warbler will continue to be a high-maintenance project—probably for as long as warblers and humans share the continent. Unlike, say, the Bald Eagle, a bird that could take care of its own recovery after humans stopped using DDT, the Kirtland’s Warbler will depend on the high-cost creation of its nesting habitat and ongoing cowbird control.

Money to maintain habitat and trap cowbirds is available through the warbler’s designation as a federally endangered species. But “when we take it off the endangered species list, that money goes away,” says Deloria, whose first job with the Fish and Wildlife Service was running the cowbird trapping program.

That’s where Marra’s research with the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center comes in. “This study that they are doing is really important,” says Deloria. “If we could operate fewer traps on the landscape, and the program costs less to operate, maybe we don’t have to raise as much money.”

Linking Summer and Winter Habitats, and the Places In Between

Marra has stalked the Kirtland’s nesting grounds for several years now. In a study published in 2009, Marra and PhD student Sarah Rockwell examined isotope signatures found in the blood, feathers, and nails of Kirtland’s Warblers to determine the conditions of their wintering habitat in the Bahamas. They recorded how early the birds arrived on their nesting grounds and how many fledglings they produced. Wetter years in the Bahamas meant more fruit and insects for warblers, earlier migration, and better reproductive success 1,400 miles north in Michigan.

“To some degree, Bahamian rainfall drives reproductive success [in Michigan],” says Marra. That knowledge may become ever more critical as sea level affects the low-lying Bahamas and a changing climate affects precipitation patterns.

Lakeland University biology professor Paul Pickhardt assisted with monitoring nesting progress in the study area. Early results show it may be possible to scale back cowbird trapping and keep the Kirtland’s Warbler population growing.

Scientists use nets to trap the birds before banding and fitting them with geolocator backpacks.

A Kirtland's Warbler caught in a net will get fitted with geolocator backpack.

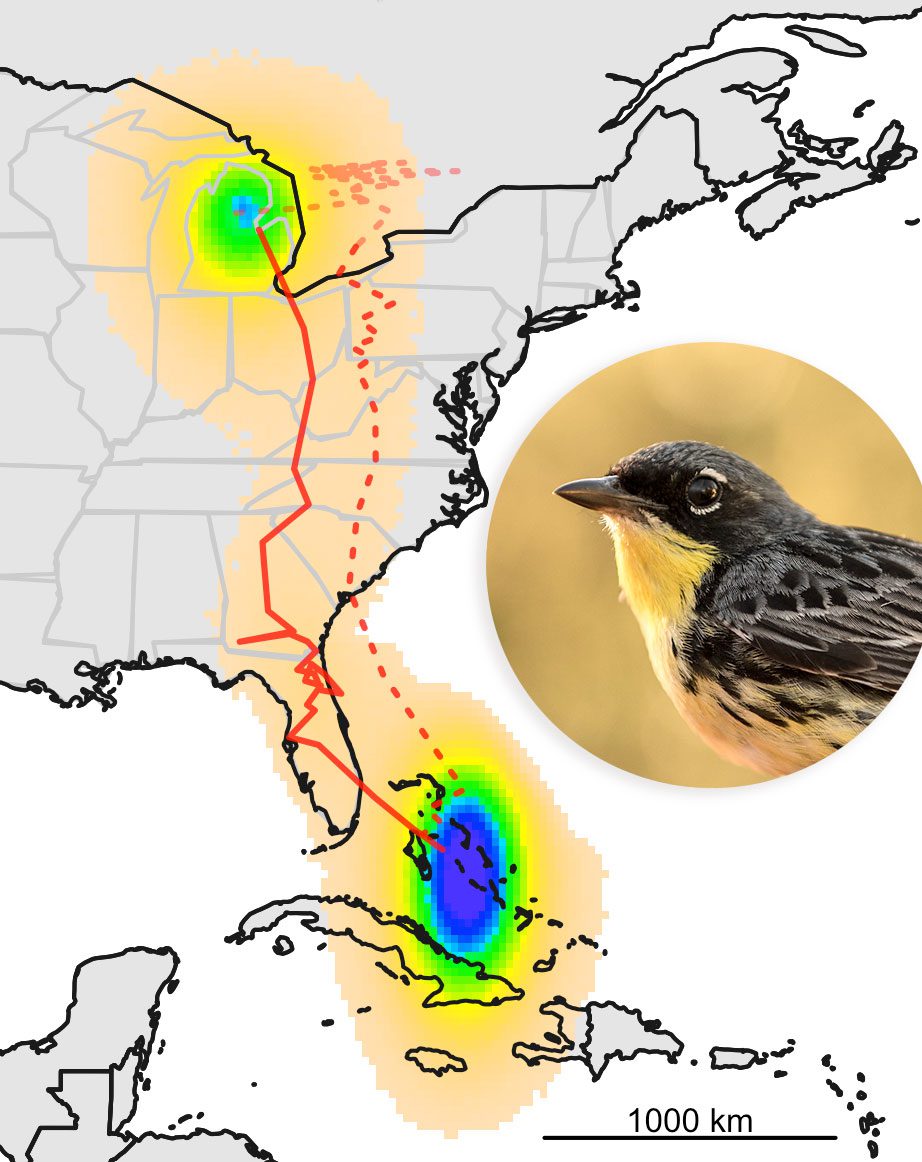

Tracking data from the geolocators helped scientists identify key Kirtland’s Warbler habitat for breeding, migration, and wintering.

The geolocator backpacks weigh less than 3 percent of the bird’s body weight.

More recently, Marra and Nathan Cooper, a postdoctoral student, fastened 0.5-gram geolocators like tiny backpacks to Kirtland’s Warblers they netted in the pines. When the birds were recaptured on the nesting grounds a year later, data stored in the tiny sensors allowed Marra and Cooper to calculate within about 120 miles the location of their wintering grounds (almost exclusively in the central Bahamas), and more important, the routes of their migration and location of their stopovers.

“We were able to identify three to five key areas during spring and fall migrations that look like they make up the really important migration stopover sites for these birds while they’re moving,” says Marra. “So this allows us to target those areas and get more and more information about birds in those spots. What are the key stopover areas? What are the key threats? It’s all ultimately going to help save the species even more than we’ve been doing now.”

On this particular morning—the summer solstice—we hike down a sandy track into the heart of a stand of young jack pine nearly a mile across, about 3 miles east of Grayling, Michigan. Most trees stand not much taller than a living room Christmas tree. As we duck into the pines, brittle lichens crunch underfoot. Among the trees, the ground is covered by blueberries, the pale green fruit the size of BBs. In another month, the berries will be ripe for birds and black bears.

For the past several weeks Cooper has been searching jack pine stands throughout the warbler’s range for nests. He and Marra are working on a study to determine the rate of cowbird parasitism and the success of Kirtland’s nesting. They have worked with the Fish and Wildlife Service to suspend cowbird trapping in certain areas to determine whether the costly control can be scaled back without imperiling the warblers’ recovery.

“Right now we have a series of [nest] sites from right next to the cowbird traps to all the way out to 12 kilometers [7 miles] from active cowbird traps,” says Cooper. “The idea was to look at how that parasitism rate varies with distance from the nearest trap.

“Historically, every Kirtland’s [nest] has been within a mile of a cowbird trap. But that rule has never been extensively tested. Basically we know it works, but it could be that five miles is fine or 10 miles is fine or that trapping every other year is fine. We don’t know. Now that they’ve met their recovery goal, it’s a little safer to play around with these things.”

Early in the season, Cooper and four assistants watched adult birds gather sedges and noted where they dove down to the base of a jack pine to build their nests. The task became easier as eggs hatched and the adults—warbling males in particular—made repeated food runs back to the nests.

“They’ll spend the majority of their time flying around collecting food, singing the whole time,” says Cooper. “You can actually hear the difference in their song when their mouth is full. They’re trying to do the same song but without opening their mouth and losing all the bugs.”

Cooper leads us to a nest location that has already been marked on his GPS. It’s tucked into a mound of shrubbery near the tip of a descending jack pine branch. He bends down, pulls the leaves aside, and peers in.

“Five nestlings,” he says. “They’re looking like six to seven days old. A couple more days they’ll be out of here, if they make it. Predation rates are pretty high during this phase. Just like it’s easy for us to find it, it is for everybody else.” Squirrels, chipmunks, snakes, feral cats, and Blue Jays all snack on Kirtland’s nestlings. Meanwhile, a male is chipping in a nearby tree. Says Cooper, “He’s a little [ticked] off right now.”

So far, Cooper and Marra are hopeful that cowbird trapping might be scaled back. Says Cooper, “This year we’re up to 90 nests so far and only one cowbird egg, infertile.”

Making Progress: From Endangered to Threatened

The Fish and Wildlife Service recommended in a five-year review completed in 2012 that the Kirtland’s Warbler be downlisted from “endangered” to “threatened.” Now, the agency is poised to go even further and take the bird off the endangered species list altogether.

The recovery team officially folded its tent in March 2016 and passed responsibilities to a conservation team, says Deloria. The conservation team—which includes some of the same researchers and administrators from the earlier team—is looking for ways, in Deloria’s metaphor, to build a three-legged stool.

The first leg, largely accomplished, is securing commitments from state and federal agencies to continue creating habitat, trapping cowbirds as needed, and monitoring the recovery. Says Deloria, “We’ve got a 40-year history of working together, so we’re not basing this on nothing. We’ve all been working together for a long time.”

The second leg is funding. Agencies are committed to creating habitat, but no one has volunteered money for cowbird trapping. “The cowbird trapping program is probably one of the biggest holes,” says Deloria. That’s why Marra’s research could be such a boon if it shows a way to reduce the intensity and cost of cowbird control.

The third leg is cultivating a friends group to support the warbler. Deloria thinks they’ve found such a group in the local Kirtland’s Warbler Alliance, a volunteer group of birders and biologists. “They can help garner more support from the local communities that we’re working in,” she says.

“It’s a pretty amazing thing that’s happened with Kirtland’s Warbler when you think about it, the amount of effort that has gone into saving the species,” says Scott Hicks, field supervisor for the Fish and Wildlife Service in East Lansing, the office responsible for much of the Kirtland’s territory. “I feel good about where we’re at and the opportunity to hopefully propose to delist it in the future.”

Hicks says the agency has received funding to begin the two-year process of downlisting or delisting, which involves writing a proposal and responding to public comments and expert opinion.

“We anticipate that the downlisting proposal will be published in the fall of 2017,” he says.

Celebrity of the Jack Pines

As our little band emerges from the jack pines, a party of bird watchers parks along the dirt road and scrambles from their cars with cameras and telescopes. The Kirtland’s Warbler has become a minor celebrity in the northern Lower Peninsula. The latest Fish and Wildlife Service survey estimated that wildlife watchers spend more than $1 billion in Michigan each year. And the magazine Bird Watching pegs the Kirtland’s Warbler as the nation’s seventh most sought-after species. Michigan Audubon runs tours out of nearby Hartwick Pines State Park, and the Forest Service offers Kirtland’s safaris out of the town of Mio.

The birders line up along the shoulder of the road. Then one spots a male Kirtland’s in the branches of a tall tree. As the warbler calls out, a ripple of excitement passes through the crowd. People adjust their optics and crane to find the distant bird in their spotting scopes and camera viewfinders.

If only they knew to relax. In just a few minutes, once they hike down the dusty path to the heart of the jack pine stand, they will no doubt find Kirtland’s Warblers all but perching on the ends of their binoculars and the brims of their floppy hats.

Greg Breining has written about nature, science, and medicine for several national publications, including the New York Times, National Geographic Traveler, and Audubon.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library