I’m seeing fewer birds in my yard. Is something affecting their populations?

Originally published April 2009. Updated January 2020.

Bird populations fluctuate seasonally and from one year to the next for a range of reasons. Often when someone reports that birds have gone missing from their yard, they are just seeing normal variation. Causes for these regular changes include:

- Fluctuating food supplies/requirements. Cones, berries, seeds, and insects change from year to year, causing birds to move about to take advantage of food surpluses and to escape from areas with food shortages. Also, birds have different dietary needs during different times of the year, so they may move to or away from your feeders seasonally. You may notice fewer birds at your feeders during the late summer and early fall as there is usually lots of natural food available.

- Weather patterns. Birds may temporarily move out of areas to avoid droughts, floods, storms, exceptional heat and cold waves, and other unusual weather conditions.

- Predator populations. Foxes, birds of prey, cats, and other predators have fluctuating populations too. When their populations are high, bird populations may fall. This can also happen on a very local scale, such when a hawk takes up residence in your yard. When the predators move on, your birds will come back. Here’s what to do about a hawk in your backyard.

- Disease. On rare occasions, outbreaks of diseases can sharply reduce numbers of certain birds. Examples include the effect of West Nile virus on crows in the early 2000s; House Finch eye disease; and salmonellosis on feeder birds. Learn more about diseases and how to keep your feeders clean.

- Habitat change. Tree removal, housing developments, land clearing, fires, and other changes can change the number or types of birds you see.

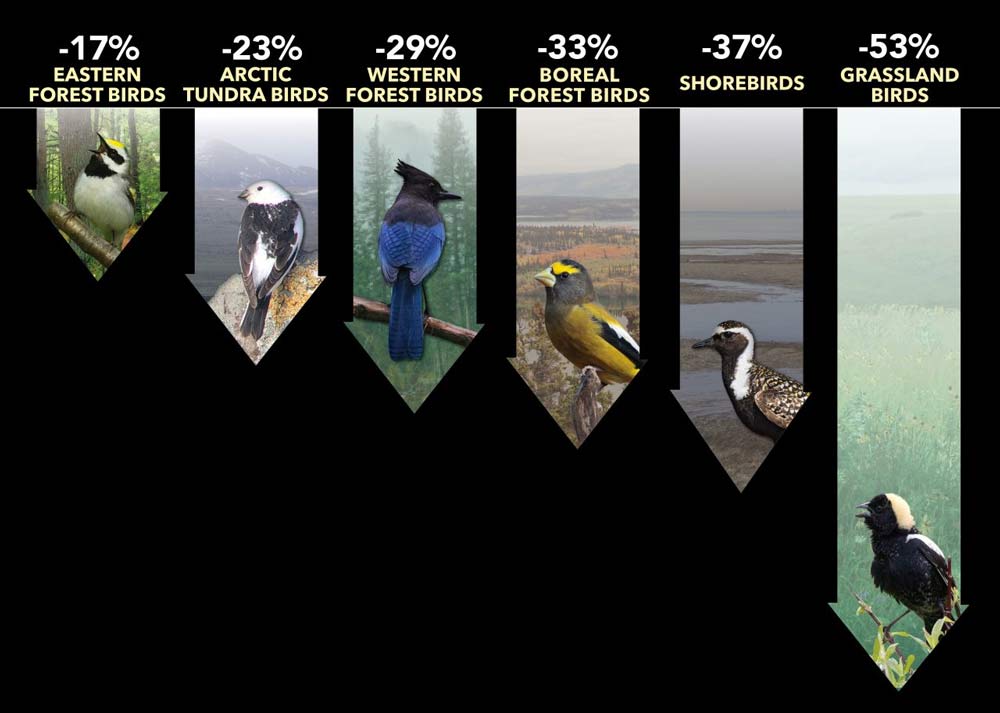

In addition to seasonal fluctuations, many bird species are declining (see sidebar). Since it is difficult for scientists to monitor birds on a continent-wide scale, science has turned to bird watchers for help via the emerging field of citizen science, which brings together thousands upon thousands of individual observations into centralized databases.

Projects such as NestWatch and FeederWatch focus on gathering information on birds during breeding and winter feeding times respectively. And one of the biggest citizen science efforts ever undertaken, eBird, allows people anywhere in the world to enter bird observations anywhere, anytime, into a worldwide database. eBird also allows you to record and organize your bird sightings, use maps to view real-time sightings of particular species, create charts detailing which birds are seen in your area, and when, and make graphs to compare species occurrence for an area over a period of up to 5 years.

Programs like Birdcast use data from sources like eBird to compile bird migration forecasts, pinpointing where species are at certain times during migration.

eBird and Birdcast are great resources to find out more about where species of birds might be after they disappear from your backyard.

Through these efforts, we are learning more than ever before about many basic questions: Where does a given species live? How abundant is it? How are these patterns changing with time? With a clearer understanding of these baselines, we are in a better position to analyze the underlying factors that are acting on bird populations, and chart courses of action for their benefit.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library