Bird ID Skills: Habitat

A habitat is a bird’s home, and many birds are choosy.

Narrow down your list by keeping in mind where you are.

April 20, 2009Identifying birds quickly and correctly is all about probability. By knowing what’s likely to be seen you can get a head start on recognizing the birds you run into. And when you see a bird you weren’t expecting, you’ll know to take an extra look.

Habitat is both the first and last question to ask yourself when identifying a bird. Ask it first, so you know what you’re likely to see, and last as a double check.

You can fine-tune your expectations by taking geographic range and time of year into consideration.

Birding by probability

We think of habitats as collections of plants: grassland, cypress swamp, pine woods, deciduous forest. But they’re equally collections of birds. By noting the habitat you’re in, you can build a hunch about the kinds of birds you’re most likely to see.

North America has more than 50 species of warblers and over 30 species of hawks. It’s impossible to keep all these possibilities straight every time you spot one of these birds. But you can make things a lot easier by considering the habitat you’re in.

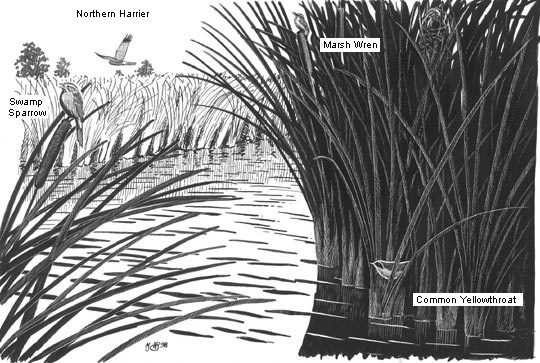

Likely species in a freshwater marsh. Typical sparrow: Swamp Sparrow (in the East); typical warbler: Common Yellowthroat; typical wren: Marsh Wren; typical hawk: Northern Harrier.

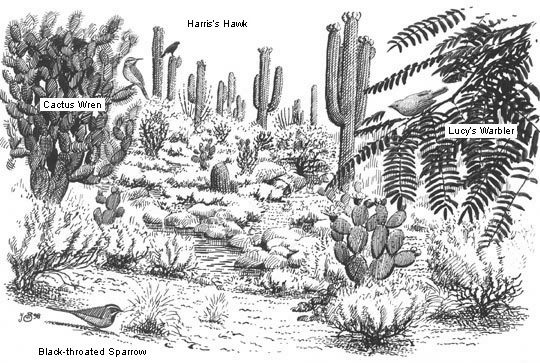

Likely species in the Sonoran Desert. Typical sparrow: Black-throated Sparrow; typical warbler: Lucy's Warbler; typical wren: Cactus Wren; typical hawk: Harris's Hawk.

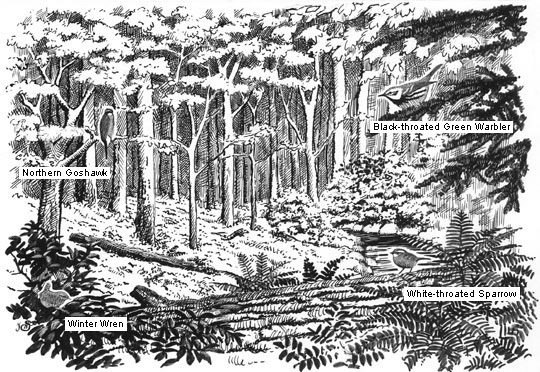

Likely species in an Eastern mixed forest of coniferous and deciduous trees. Typical sparrow: White-throated Sparrow; typical warbler: Black-throated Green Warbler; typical wren: Winter Wren; typical hawk: Northern Goshawk.

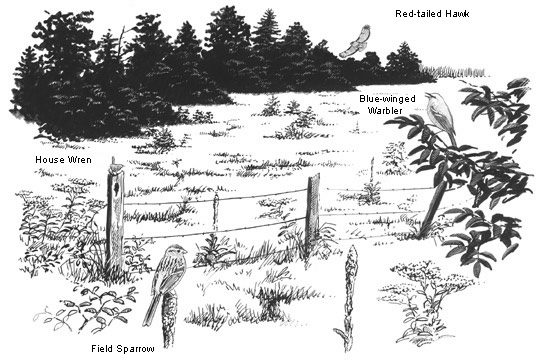

Likely species in an old field in the Northeast. Typical sparrow: Field Sparrow; typical warbler: Blue-winged Warbler; typical wren: House Wren; typical hawk: Red-tailed Hawk. Images by John Schmitt/Cornell Lab.

For example, your field guide shows lots of sparrows with rusty heads, but you can use habitat and probability to winnow them down. Is yours hiding in a bunch of reeds, hopping around the base of a pine, or singing from a fencepost? The reeds tell you it’s probably a Swamp Sparrow. If you’re in pine woods, it’s more likely a Chipping Sparrow. And if it’s along a fencerow it could well be a Field Sparrow. Click through the illustrations at right for more examples.

Of course, if you only let yourself identify birds you expect to see, you’ll have a hard time finding rare or unusual birds. But the best way to find rarities is to know your common birds first. (The ones left over are the rare ones.) Birding by probability just helps you sort through them that much more quickly.

Use range maps

California Quail are birds of the Pacific Coast and Great Basin. Meet their desert cousin on the next slide. Photo by Len Blumin via Birdshare.

Gambel's Quail live in the Desert Southwest. Their range overlaps very little with California Quail.Photo by Joan Gellatly via Birdshare.

Young orioles can be confusing, but an orange oriole in the East is most likely a Baltimore Oriole. Meet its western counterpart on the next slide. Photo by birdsandwater via Birdshare.

In spring and summer, Bullock's Orioles overlap with Baltimore Orioles only in a narrow region where the Rockies meet the Great Plains. Photo by Sam Wilson via Birdshare.

The Pygmy Nuthatch is a tiny nuthatch of western pine forests. Meet its southeastern lookalike on the next slide. Photo by Lorcan Keating via Birdshare.

Brown-headed Nuthatches look very similar to Pygmy Nuthatches, but the farthest west they occur is the pine flatwoods of East Texas. Photo by Mike Powers via Birdshare.

You don’t have to give yourself headaches trying to keep straight every last bird in your field guide. They may all be lined up next to each other on the pages, but that doesn’t mean they’re all in your backyard or local park.

Make it a habit to check the range maps before you make an identification. For example, you can strike off at least half of the devilishly similar Empidonax flycatchers at once, just by taking into account where you are when you see one. Baltimore Orioles look a lot like Bullock’s Orioles, but you’re unlikely to be in a place where you can see both at the same time. Similarly, North America has two kinds of small nuthatches with brown heads, but they don’t occur within about 800 miles of each other.

Of course, birds do stray from their home ranges, sometimes fantastically – that’s part of the fun. But remember that you’re birding by probability. First compare your bird against what’s likely to be present. If nothing matches, then start taking notes.

Check the time of year

The silky-plumaged Cedar Waxwing breeds across northern North America and winters in southern states. Next up: meet its winter replacement.Photo by cdbtx via Birdshare.

As Cedar Waxwings fly south in fall, Bohemian Waxwings arrive in northern states from Canada and the Arctic. Photo by Joanne Bovee/Cornell Lab.

The Field Sparrow is common in summertime across eastern North America. Photo by Jim Paris via Birdshare.

You're not likely to see American Tree Sparrows until after Field Sparrows have flown south. Photo by Kevin Bolton via Birdshare.

Your field guide’s range maps hold another clue to identification: They tell you when a bird is likely to be around. Some birds don’t move much throughout the year – nuthatches, chickadees, and many woodpeckers are good examples. Others leave North America entirely. And a few come south from the Arctic to spend their winters with us. That information can help you.

Many of summer’s birds, including most of the warblers, flycatchers, thrushes, hummingbirds, and shorebirds, are gone by late fall. (Or, if you live in southern or coastal parts of the country, this may be when birds start arriving in your area.) Other birds move in to replace them. This mass exodus and arrival is part of what makes bird watching during migration so exciting.

For example, Cedar Waxwings move south for winter, but Bohemian Waxwings replace them across much of northern North America. Field Sparrows depart as winter approaches, just as American Tree Sparrows are arriving.

Find out what you’re likely to see: Use eBird

While range maps are a good starting point for learning where and when you’ll find a certain bird, there’s only so much detail that will fit on one map.

For ways to get more detail about what birds are near you, try using the online tools at eBird. It’s a free checklist program that lets you keep track of birds you’ve seen.

The great part about this system is that eBird also lets you look at the data that other bird watchers have recorded. When you visit the eBird tools page, you can view bar charts and range maps generated for any species, time period, and location you choose.

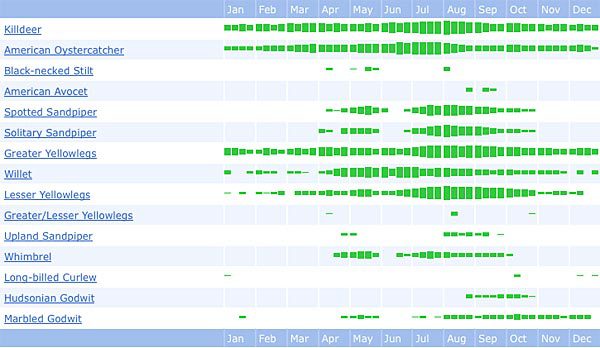

The bar charts that eBird produces give you a sense for how often a species has been detected in a certain region. It’s a great way to see what birds you can expect to see in your state, county or a nearby birding hotspot (such as a national wildlife refuge or state park).

You can also use eBird to look at arrival and departure dates for migrants as well as high counts, either for a certain year or a range of years.

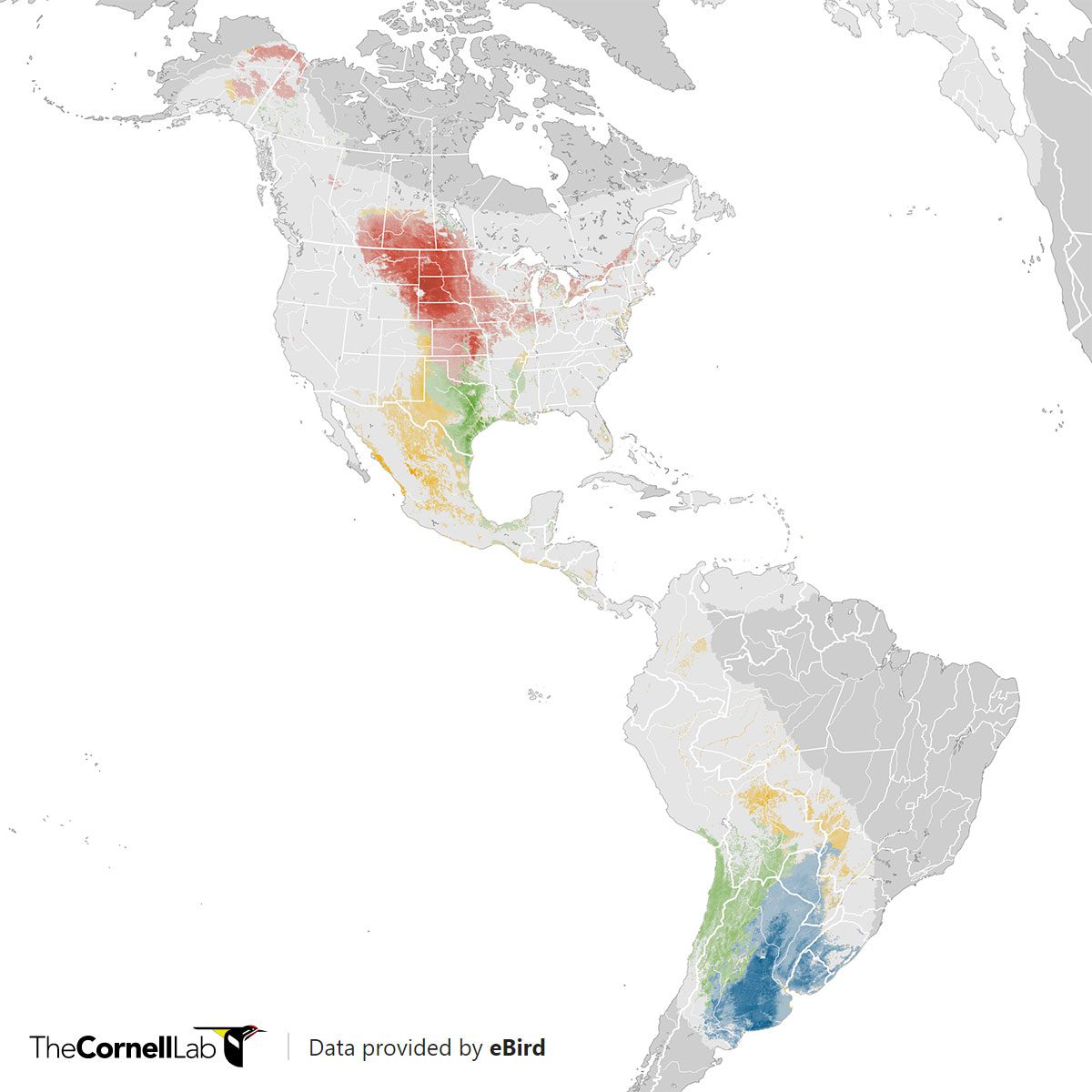

We’ve also put the immense eBird database (provided by bird watchers like you) to use making animated occurrence maps—the animated Upland Sandpiper map is pictured here. These novel maps let you see how a bird’s range changes in the U.S. from week to week throughout the year.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library