Can the Clark’s Nutcracker Help Its BFF, the Whitebark Pine, Recover from Disaster?

Clark's Nutcrackers and whitebark pine have deeply intertwined lives. If and when the pine is listed under the Endangered Species Act, the tree's recovery could depend on its birdy best friend.

December 14, 2022From the Autumn 2022 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

Published September 2022; updated December 2022 to indicate the whitebark pine’s official listing as Threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

Some pairings are so iconic that one is not complete without the other: Macaroni and cheese. Abbott and Costello. Peanut butter and jelly. In the northern Rockies and Sierra Nevadas, that duo is the whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis) and Clark’s Nutcracker (Nucifraga columbiana).

The pine produces large, energy-rich seeds that the nutcracker caches by the thousands, burying them in the soil or gravel of mountain slopes as a stashed food supply to get the birds through the long, frigid winters. But the seeds that aren’t retrieved germinate where they are buried—growing into the next generation of whitebark pines.

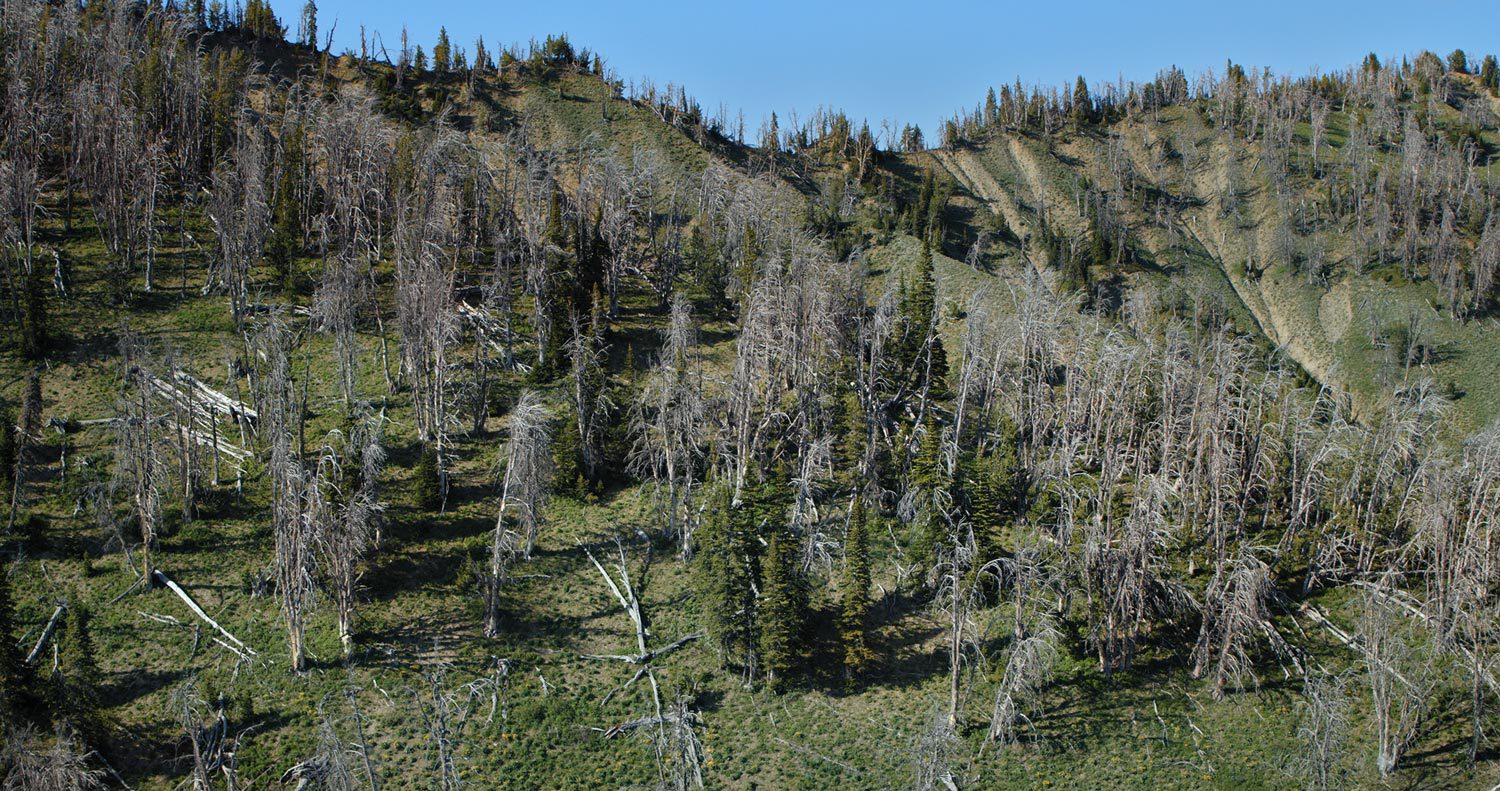

In some high-alpine forests of the West, virtually every whitebark pine on the landscape sprouted from seeds planted by a nutcracker. In the past few decades, the dual threat of a fungal disease and a forest pest have wiped out vast areas of whitebark pines. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimates that over half of all whitebark pines have died, with much of that destruction happening in the last two decades. Without action, says Robert Keane, an ecologist at the U.S. Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station, whitebark pine forests could be gone in a century.

That action could be coming soon; as of late summer, the USFWS was in the final stages of considering the tree for listing as Threatened under the Endangered Species Act. A final listing decision could be announced this autumn [update: the USFWS officially listed the whitebark pine as Threatened in December 2022], a move that will require federal agencies to create comprehensive, proactive restoration plans to ensure that the trees are around for future generations.

Many ecologists say the listing is long overdue.

“Whitebark pine has been a candidate species [for ESA listing] for a long time,” says Diana Tomback, an ecologist at the University of Colorado Denver. “The listing decision is a long time in the making.”

Tomback is a lead scientist on the National Whitebark Pine Restoration Plan, a strategy for bringing the tree back that was produced by a partnership between the Whitebark Pine Ecosystem Foundation and the nonprofit conservation group American Forests. The plan draws from Tomback’s four-decade career as a scientist studying the relationship between whitebarks and nutcrackers.

“The National Whitebark Pine Restoration Plan relies on the Clark’s Nutcracker to disperse the pine beyond restored areas,” she says. “The bird is literally the key to saving the whitebark.”

But the bond between whitebark and Clark’s Nutcracker is at risk, too. Research by Taza Schaming, a wildlife ecologist at the Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative, has found that areas with fewer whitebarks also had fewer nutcrackers. And fewer nutcrackers means fewer birds to plant the next generation of whitebarks.

A Bond Between Bird and Tree

In the 1980s, Tomback was a grad student doing PhD work at the University of California, Santa Barbara. On a hiking trip in the Sierra Nevadas, she was taking a rest beneath a whitebark pine tree when she was visited by a Clark’s Nutcracker. After that spark moment, she became fascinated with what locals called a “pine crow” and its affinity for whitebarks.

Tomback would go on to conduct groundbreaking research that documented how nutcrackers cache several thousand whitebark pine seeds in the summer and autumn—burying caches of anywhere from 2 to 10 seeds a few centimeters under the soil. Tomback was the first scientist to show that it was the nutcrackers that were dispersing whitebark seeds and helping the pine spread. The birds generally cache three to five times more seeds than they’ll ever eat, driven by the biological need to collect and bury when times are good. From an evolutionary standpoint, the whitebark pines are counting on the nutcrackers to do this planting. Whitebark pine cones don’t open on their own, and the seeds have no wings for wind dispersal. Instead, the tree produces large, fatty seeds—with all the pine cones clustered at the very top of the tree—to attract nutcrackers.

“It looks like a platter of food when the birds fly over,” says Schaming.

Schaming earned her PhD through Cornell University in 2016 while running the longest field study ever conducted on Clark’s Nutcrackers—a 14-year research project on the foraging behavior and habitat use of nutcrackers in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem [see Soul Mates, Living Bird Autumn 2015]. By monitoring nutcrackers via satellite-tracking tags, she revealed that nutcrackers will travel over long distances to find whitebark pine stands as food sources and plant seeds across a landscape.

“These cones don’t open by themselves. They don’t open from fire,” Schaming says. “Their only means of dispersal is the Clark’s Nutcracker.”

Blister Rust and Beetles

About 40 years ago, biologists began noticing that the threads of mutualism between the Clark’s Nutcracker and the whitebark pine were fraying. Like many five-needle pines—including limber pines, bristlecones, foxtail, and white pines—whitebarks are susceptible to blister rust. The disease, caused by the invasive fungus Cronartium ribicola, had been causing problems since its accidental importation in the early 1900s. By the 1980s, Keane began noticing large outbreaks of blister rust all over the West, with three-quarters or more of the whitebark pines killed in an outbreak area.

Nutcrackers and Whitebark Pine

Around the same time, foresters took note of another threat—the mountain pine beetle (Dendroctonus ponderosae). Though it’s a native pest that rarely caused major problems to whitebarks (historically, the high latitudes and elevations favored by these pines meant winter cold snaps killed many beetles), the warmer winters brought on by climate change have tipped the balance in the beetle’s favor. In the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, the combination of pine beetle and blister rust meant that more than half of all whitebark stands were dead by the early 2010s. Across the West, whitebark forests were wiped out in Montana, Wyoming, Oregon, Washington, and Idaho.

The die-off is about more than just one tree, as the whitebark pine is a keystone species—the pine’s fatty seeds provide food for more than 100 animal species, including grizzly bears, red squirrels, and Cassin’s Finches. Whitebark pines are also the first tree species to sprout after fire and secure the soil while acting as nurse trees for other spruces and firs. And whitebarks play a vital role in providing shade that keeps snowpack from melting quickly at high elevations, which regulates the flow of water down into western valleys.

“This tree is the glue that holds the ecosystem together,” Keane says. Losing the whitebark pine, says Keane, would create a ripple effect that would reverberate throughout the mountain West. The intimate relationship between whitebark pines and Clark’s Nutcrackers means the die-off among trees could be bad news for the birds. Although nutcrackers can—and do—eat other foods, it’s hard to beat the nutritional value of a whitebark pine nut (which ounce for ounce is about calorically equivalent to Nutella). A bird must eat 20 Douglas-fir seeds to get the same energy as a single whitebark seed.

Given the loss of whitebarks, some scientists worry about subsequent declines in Clark’s Nutcrackers. In areas with the largest declines in whitebark numbers, nutcracker numbers have plummeted by almost 80%.

But it’s hard for ornithologists to know what’s happening with the overall Clark’s Nutcracker population across their entire range of 11 western states and two provinces, because nutcrackers are an irruptive species—going where the food is, happy to nest and breed wherever pine cones are plenty, and not hesitant to pack up and move if food becomes scarce. Schaming’s work shows that in years when the whitebark pines produced fewer cones, 71% of the birds she was tracking left the Greater Yellowstone area, only to return the next year.

In Washington State, however, the birds stayed put when whitebark pine cones were scarce. Schaming believes that’s due to one major difference.

“They have ponderosa pines in Washington. So there’s another food source to keep them stationary,” she says.

Schaming has also found that even a few cone-bearing whitebark pines, even just some bedraggled holdouts, can keep Clark’s Nutcrackers on the landscape. As long as the birds have a large area to call home and at least some whitebarks— along with Douglas-firs or other pines as alternative food sources—they should remain in the area, according to a 2020 study by Schaming that was published in PLOS ONE.

And keeping nutcrackers on the landscape is the key to bringing back the whitebark pine. Because if the birds disappear, “that’s going to make it harder for the trees to come back. It’s a feedback loop,” says Chris Ray, a research ecologist with The Institute for Bird Populations. “In order to make sure that the pine can regrow, we need to keep the nutcracker around, too.”

For Whitebark Recovery, the Bird Is Key

Schaming, Tomback, and many other scientists have been pushing the USFWS for several years to provide Endangered Species Act protection to whitebark pines. Now they say the restoration plan needs to roll out fast—because whitebark numbers are diminishing quickly, and time is not on their side.

“It takes a really long time for a 700-year-old tree to be replaced,” says Nancy Bockino, a biologist with Grand Teton National Park and a mountain guide. “It’s desperate that we do something now.”

The U.S. Forest Service has started breeding whitebark pines that are resistant to blister rust; these seedlings can be planted in areas that have lost the most trees. But any human efforts to replant entire mountainsides of disease-resistant whitebark pines will be dwarfed by the Clark’s Nutcracker— which can cache up to 100,000 seeds in a single year, and do it for free. Tomback estimates that nutcrackers provide an ecosystem service that equates to $2,500 per hectare, the equivalent cost of U.S. Forest Service seeding. With labor shortages hitting the Forest Service like everywhere else, the agency may not have the necessary resources for massive replanting efforts.

To facilitate free labor by nutcrackers, the National Whitebark Pine Restoration Plan recommends the creation of so-called “nutcracker openings,” or cleared areas with lots of room for nutcrackers to cache their favorite seeds.

According to Tomback, the dispersal of those specially bred blister-rust-resistant pines across landscapes—and full recovery for the whitebark—will rest squarely on the feathered shoulders of the Clark’s Nutcracker.

“No other tree depends on an animal so intimately,” Tomback says.

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly referred to ponderosa pine as one of the five-needled pine species that are susceptible to blister rust disease. The sentence should have included white pine, not the three-needled ponderosa pine. The sentence has been corrected.

Carrie Arnold is a freelance science writer whose work has appeared in the Washington Post, Scientific American, Audubon, and Slate.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library